We recently put in a stocktank water feature in the backyard, got a pump to circulate water and a bunch of pretty good rocks to make a little cascade, and we’ve got grand designs regarding water plants – there’s some good Texas native pond flora out there, including a native pitcher plant from east Texas, that I want – but the real hope is that we’ll have a good habitat for frogs and toads. When we first moved to the neighborhood in 2019, the warm summer nights were FULL of frogsong at every house with a water feature, and we’ve seen plenty of toads and such hanging out in our garden. Big fan of frogs, is what I’m saying here, so HOPEFULLY that will put me in good with the subject of today’s story, “Frogfather” from Weird Tales, November 1946, by the one and only Manly Wade Wellman.

Wellman is, if not obscure, then at least of specialist interest these days – if you’ve ever played Dungeons & Dragons, then you owe him more than you probably realize, since Gygax and Arneson pulled a number of monsters directly from his stories, as well as using his “John the Balladeer” character as the basis for the “Bard” class in the game. In his heyday, however, Wellman was a prolific pulp writer, and in the 40s and 50s was one of Weird Tales’ major talents. He’s an interesting guy with an interesting biography, although it *may* have been a little embellished and romanticized.

Briefly, Wellman was born in 1903 in a port city in what is now Angola. His father, Frederick Creighton Wellman, was stationed there as a medical officer for a British charity, and seems to have been quite a weird and colorful character himself. A specialist in tropical medicine, Wellman pere was famous in the international press for having “gone native” while in Africa, whatever that means. He helped build railroads and ran medical centers while there, and while he was doing missionary work he also apparently took the time to learn local languages and record local stories and beliefs. Old Man Wellman was one of those tropic-lovin’ anglos; he ended up working for United Fruit in central America, and became quite an authority of tropical diseases.

Stories about Manly Wade Wellman’s childhood in Africa are romantic (and suspect in my opinion); he supposedly spoke a native dialect before he learned English, and had been adopted by a “native chief” after his father had cured the potentate of his blindness; to me that sounds like the usual kind of nonsense expats like to brag about. What is true, though, is that his time as a child in Africa was very foundational to his outlook on life – a love of wilderness and a certain (though paternalistic) regard for people of different races, creeds, and backgrounds is evident in his work. He was also one of those people from Old South stock that liked to talk up their Native American ancestry, something that will have relevance in the story today, I think. He was an inveterate Confederate apologist, especially when around “Yankees,” apparently; you get the feeling that he was one of those romantic Lost Cause-ers who felt that there was, shall we say, a certain “order” to the world that those outside of the antebellum South could never truly appreciate or understand. His stories with black American characters clearly reflect this world-view; reminds me a little of Flannery O’Connor’s racism, honestly.

The Wellman family would move back to the U.S. when Manly was a kid; he did his schoolin’ here in the States, got a degree in Literature and Journalism, and went to work as a reporter in the 20s. It was during this time that he toyed around with fiction, selling a few stories to Farnsworth Wright at Weird Tales here and there, mostly based on childhood tales of Africa. He met and became friends with some of the early sci-fi and fantasy writers of that era, like Al Bester and Henry Kuttner, when he moved to New York. He also knew and travelled with the famous Ozark folklorist Vance Randolph, visiting Appalachia and getting a strong sense of the traditions and folklore of the area, something that would loom large over his career, as we’ll see in this story.

A hugely prolific writer, in the 30s and 40s he was also a major contributor to Weird Tales, producing a number of very popular “occult detective” style stories, as well as a lot of straight horror tales, usually set in either Africa or Appalachia. As mentioned above, later in his career, in the 60s, he’d invent his most famous character, “Silver John,” a wandering troubadour country boy who faced eldritch evil and dark magic in the hills and hollers of Appalachia with only his wits and his silver-stringed guitar. They’re good stories and worth hunting up – there was a recently republished collection from Valancourt, “John the Balladeer,” that I’d recommend, if that sort of thing sounds interesting to you.

One last little anecdote that I find hilarious – in 1946 Wellman won the Ellery Queen Mystery Award for a story of his (“A Star for a Warrior”), beating William Faulkner, who was apparently absolutely furious that he’d taken second place to a “mere science fiction” writer. Faulkner was apparently so pissed off that he wrote a long angry letter to the editors of the Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, wherein he explained that he was, simply, the greatest living American Writer and they could all go to hell. Pretty funny!

Enough of these maunderings! Lets get down to business!

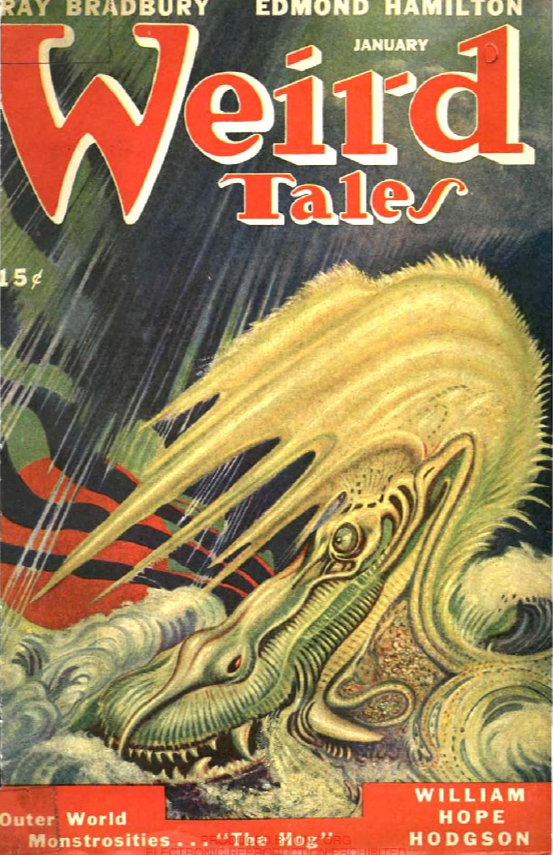

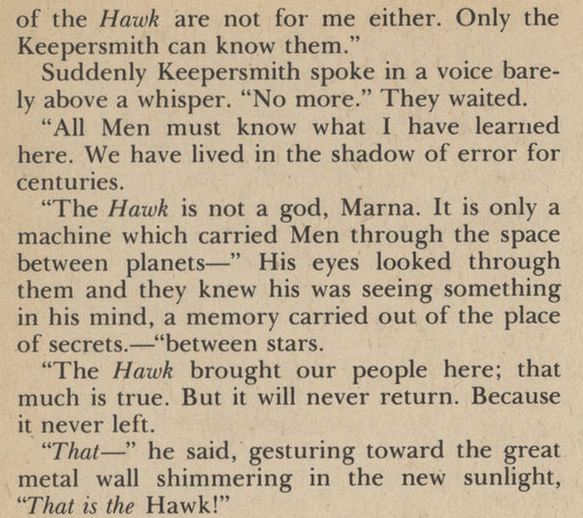

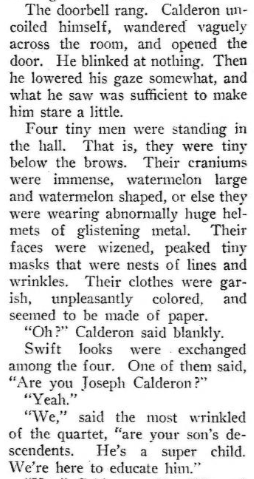

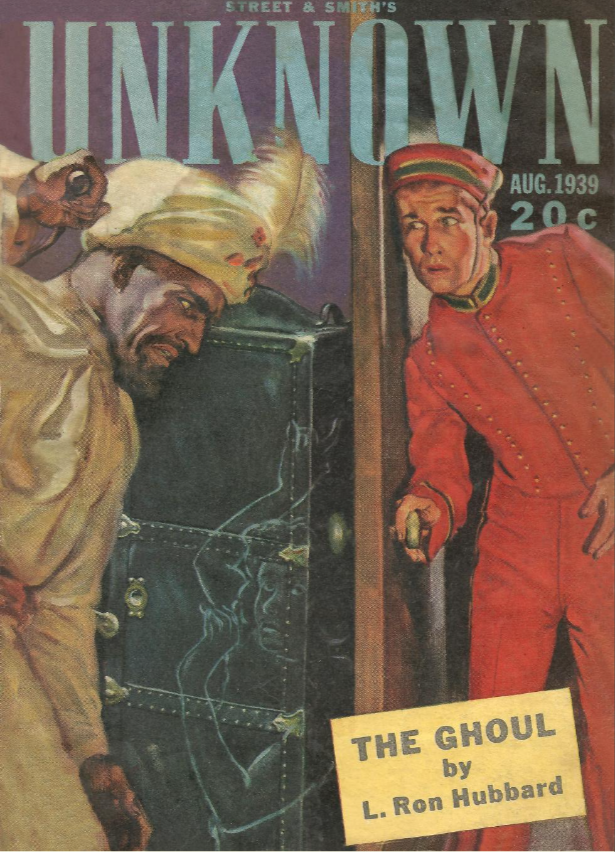

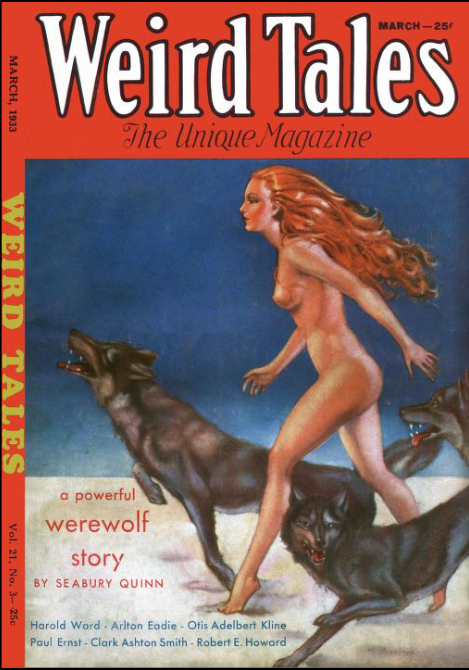

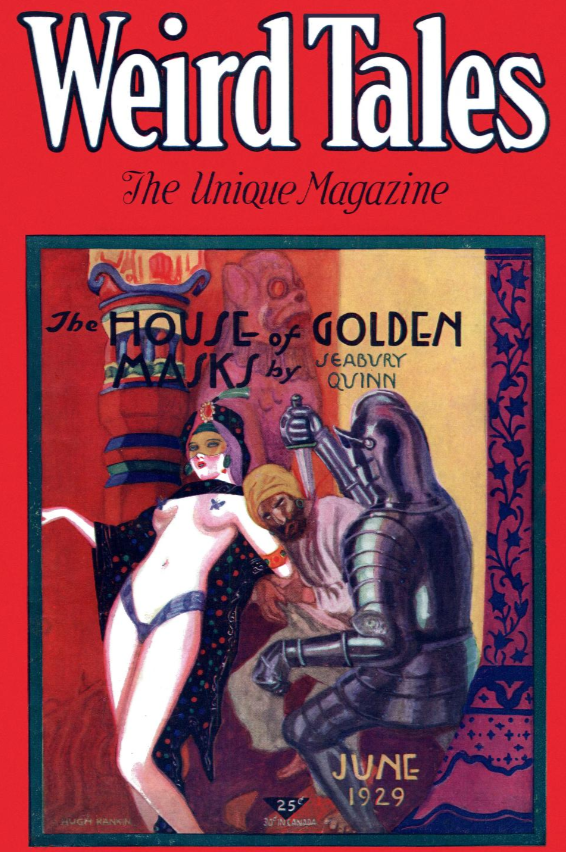

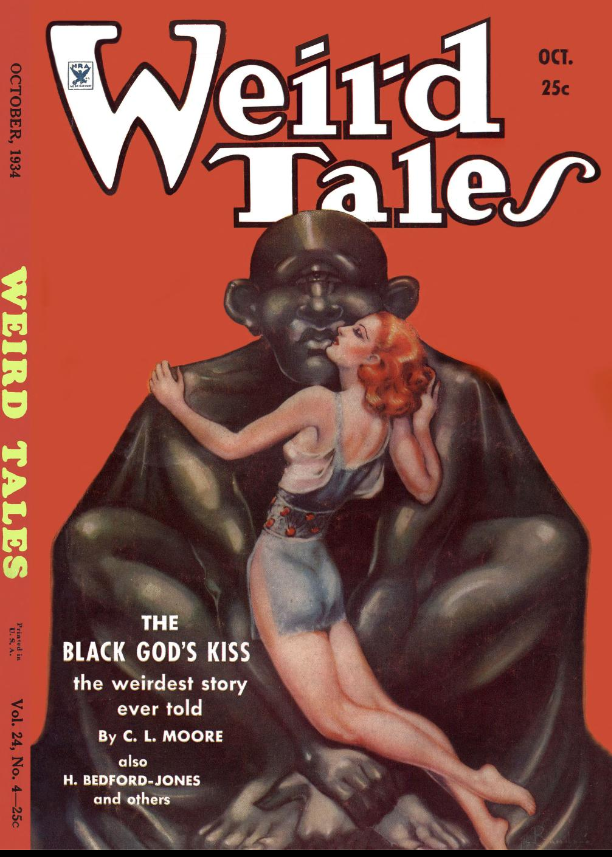

Lookit that cover, hot damn! Spectacular pic from Boris Dolgov, another one of those Maxfield Parrish influenced artists producing some of the best, most vivid work that ever appeared on the cover of a magazine. Dolgov, about whom almost nothing is known, did some spectacular work for Weird Tales in this era – I love the weightlessness of his figures, and the sharp, dangerous feyness that he invested in his otherworldly figures – that nereid or siren or whatever, the naked blue-green lady…she’s delicate and cute, sure, but there’s also a feral otherness to her that is just unbeatable. Spectacular stuff! Between Dolgov, Bok, and Coye, the 40s and 50s editions of The Unique Magazine are some of the best lookin’ ever made.

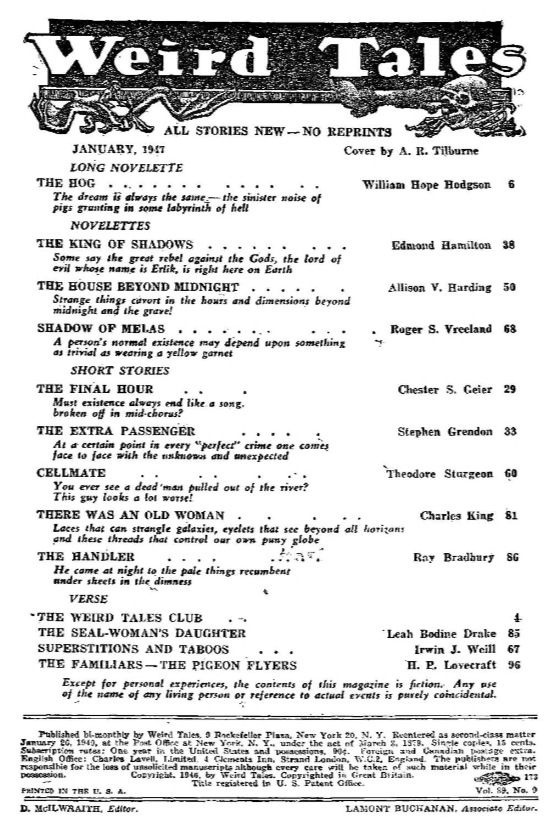

ToC’s pretty good this time around, too – Quinn is still out there, fightin’ the good fight, and you’ve got the enigmatical Allison V. Harding up there too, a mysterious woman about whom almost nothing is known (there’s some suggestion that she was, actually, Jean Milligan, the wife of Lamont Buchanan, the associate editor of the magazine). Bradbury, Derleth, Bloch, and Wellman – this is a relatively heavy-hitter of an issue for this late 40s era! Anyway, on to our story!

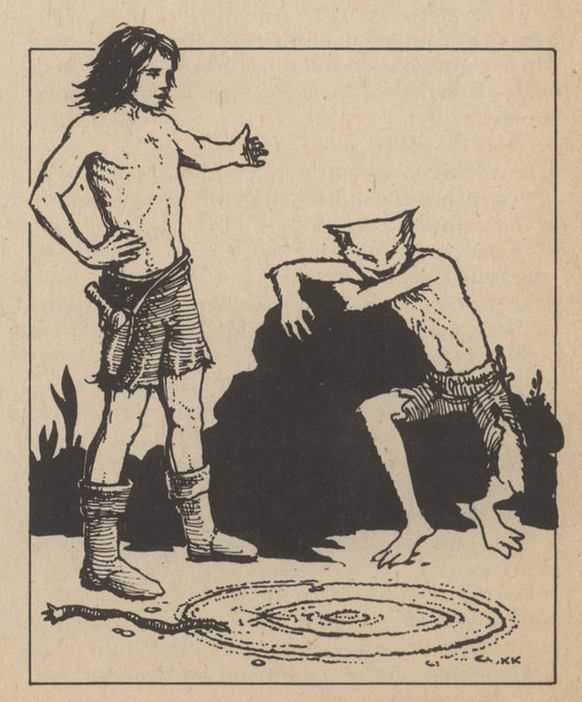

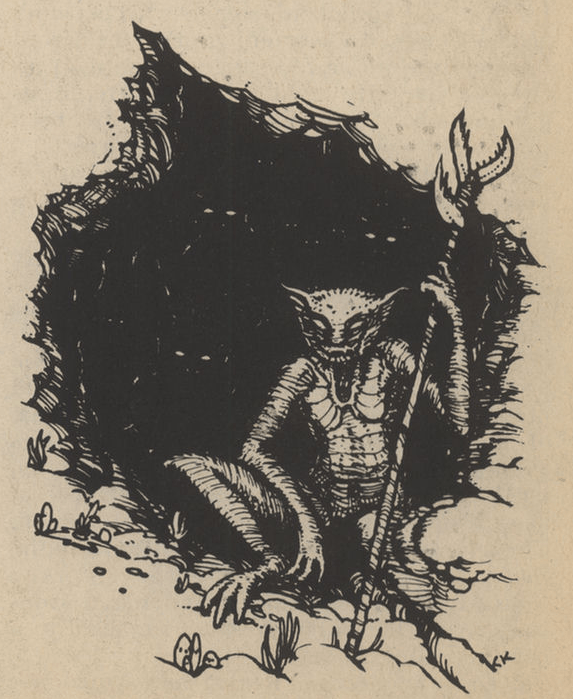

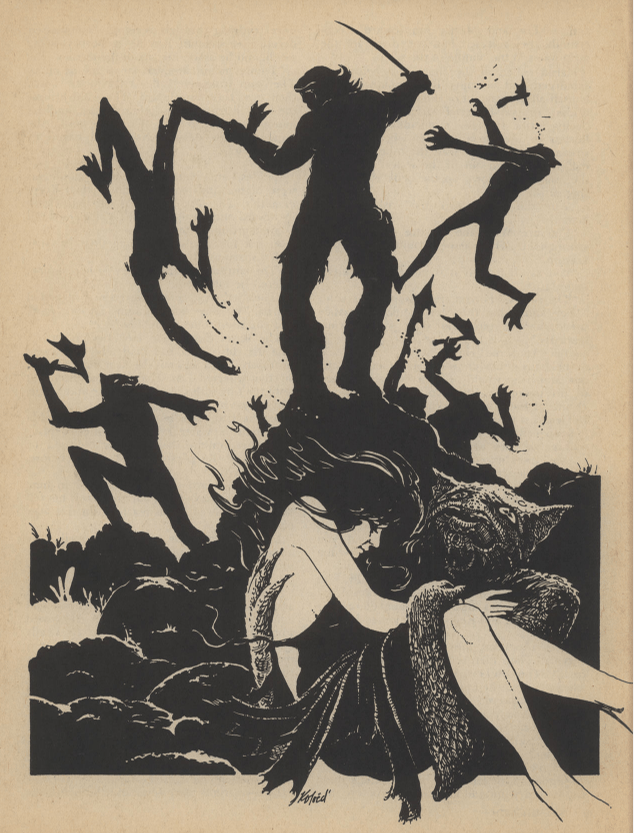

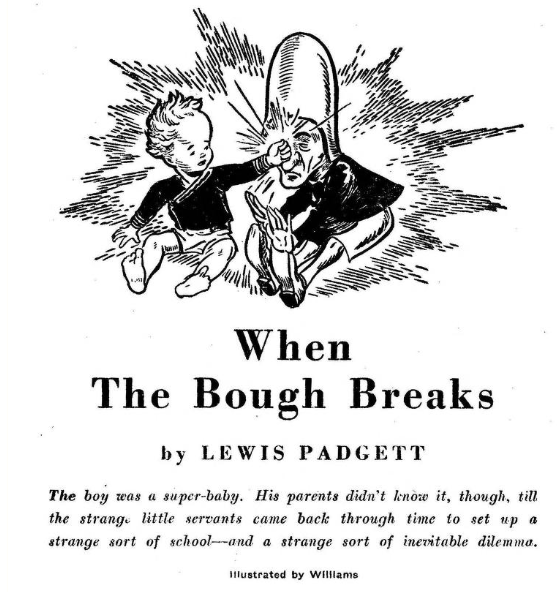

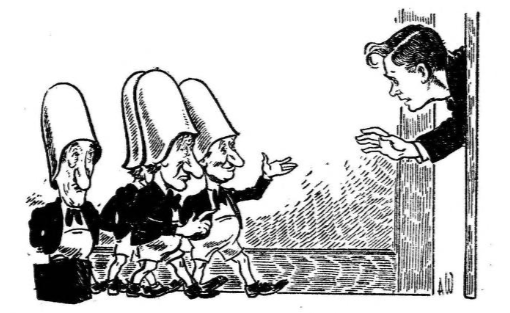

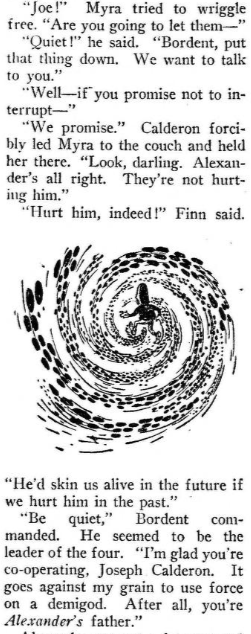

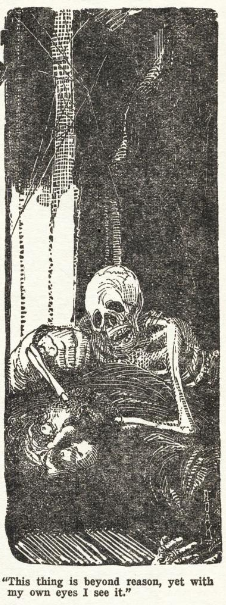

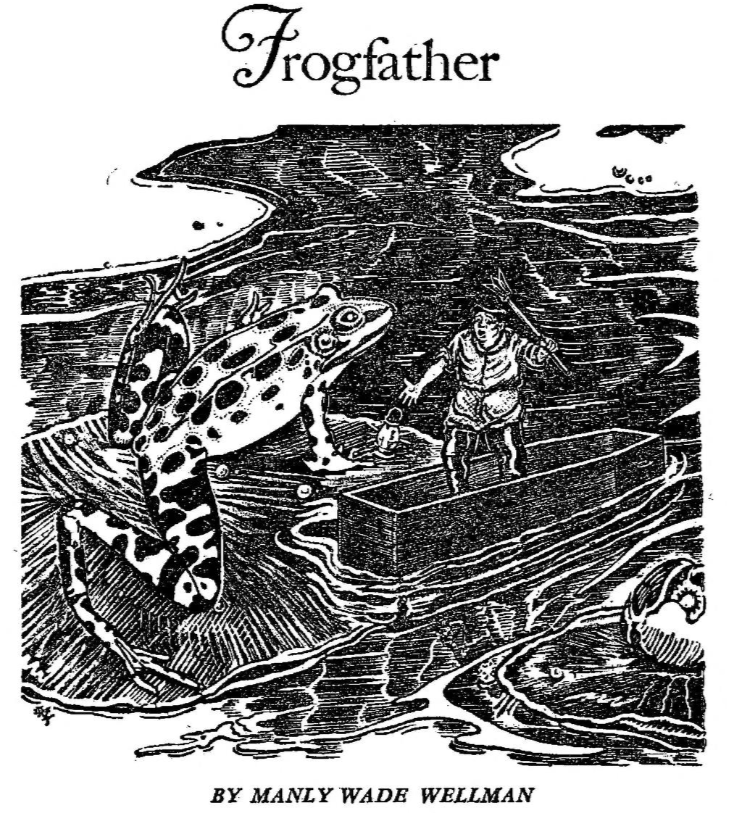

A.R. Tilburne again doin’ great work…guy in a coffin boat bein’ menaced by a Big Frog. Solid, fun piece.

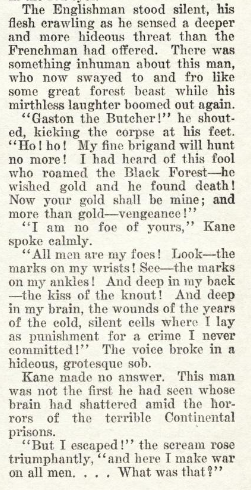

Our story starts with the narrator explainin’ how he never liked frogs’ legs, but he sure as shit wouldn’t eat ’em now, not after what happened. A good, snappy little entry into the story, and one that preserves what I think is the key *tale* part of the genre of the weird tale. This is some guy tellin’ us a tale, and there’s an intimacy and immediacy to that kind of framing device that I think helps us step right into the proper frame of mind to enjoy what is sure to be a weird-ass story. Anyway, our narrator introduces us briefly to Ranson Cuff, a moneyed asshole who, through his financial clout, basically rules the Swamps.

Good, efficient characterization, with the unmistakable “backwoods” voice of Wellman here, setting up a petty tyrant asshole that nobody likes. But what’s Cuff got to do with frogs’ legs?

Not only is Cuff a bastard, he’s flat-out evil too! Cruel, sadistic, and he’s keeping our narrator as an indentured servant. We are quickly establishing the fact that Cuff is the guy who absolutely deserves to die, one of the most important aspects of a horror story. He’s an evil guy in a boat he’s repossessed out huntin’ for frog legs with his slave and an oppressed minority. The frog legs are a nice touch, too – they’re almost automatically a very special kind of prey, you know what I mean? Like they’re a symbol of explicit cruelty already, way more so than if this guy was out fishing or hunting ducks, right? The fact of their dismemberment is right there in the name, and Cuff enjoys that aspect maybe even more than the eating of them. Solid stuff, and again, very efficient.

Cuff and his unfortunate cronies are out paddling around the swamp, looking for frogs to gig and havin’ a hell of a time of it – there doesn’t seem to be any frogs along the banks. Cuff, angry and frustrated, orders his men to paddle him up to a secluded neck of the swamp that he’s never been in before, but where he can hear the frogs calling. Our narrator starts paddling, but his comrade pulls his paddle from the water and stops the boat.

And there he is, the titular Frogfather himself. This old, nameless, stereotyped Indian, who speaks better than either Cuff or the narrator, tries to stop Cuff from heading into that particular stretch of the Swamp, on account of it being home to, basically, a big ol’ Frog God. Wellman has given it a suitably “exotic” sounding name, one he made up whole clothe, and it’s basically the only real misstep in the story, in my opinion. “Frogfather” is, simply, way cooler and way more menacing a name than this fake Native American word that he’s invented. I mean, christ, I wanna start a speed metal band called “Frogfather” right now, don’t you? It’s a rad name!

Of course, Cuff can’t believe what he’s hearing – he don’t give a shit about Frogfathers, he wants some extra-cruelty supper, and he wants it now! He tells the nameless Indian to shut up and get paddling, which, of course, the nameless Indian refuses to do.

Wellman underlining once again what a fuckin’ piece of shit Cuff is for us. He makes the nameless Indian *swim* to shore! No question: Cuff is DEFINITLEY going to die now. One of the fun parts of weird fiction, for me, is the sense of the shape of the story coming along as you read it – we know that Cuff is in trouble, and Wellman WANTS us to know that, which is part of the pleasure – Cuff, that asshole, has no clue what’s about to happen to him!

Johnny, our narrator, paddles them to the distant neck, and they see a strange sight. The water here is phosphorescent, glowing faintly and eerily as they slip silently into this forbidden corner of the swamp. Cuff can’t be bothered with it though, since there’re frogs to kill!

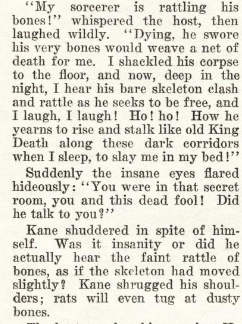

Pretty brutal frog murder there, isn’t it? The gaping mouth, the smacking it alongside the boat to make it stop its squirming, grim stuff. Cuff’s bloodlust is up now – he sees another one and wants more! But, as they’re trying to maneuver towards it, the boat starts to wobble and tip. Cuff curses Johnny, and tells him to hold the boat steady. Johnny says he IS holding the boat steady, it’s Cuff in the prow that’s causing the imbalance, which, of course, Cuff denies. Must be a snag, Johnny figures; he takes the lantern and peers over the side of the boat, trying to spot whatever it is they’re caught up on.

Hell yeah, it’s the Frogfather!

The story wastes NO time – Cuff goes into The Forbidden Swamp, kills a frog, and BAM! Frogfather is on the scene! No lurking about or skulking or haunting – you piss of Frogdaddy, you get walloped.

I like the description of the Big Frog here – the line about the eyes being “every jewel-flashing color known to the vainest woman” is both fun and shows Wellman’s ear for backwoods eloquence. The neat thing, too, about the Frogfather is that it’s purely the size and bulk of the thing that’s alien; other than that it is, simply, a Big Frog, and honestly that’s something I appreciate. There’s no reason for this thing to be some kind of eldritch abomination, or even something “frog-like” akin to Clark Ashton Smith’s Tsathoggua – this thing, which has some mythic, folkloric, primal linkage to frogs and their lives, appears as a truly big frog, simple as. I think that makes the weirdness of its actions, in the section above and what we’ll see in a bit down below, all that much weirder, too. It heaves itself up onto the boat, casually snaps Cuff’s iron gig, and then tips the boat, grabbing Cuff by the head and neck – the monstrousness of the Frogfather is in the incongruity of its very deliberate, almost human-like, actions.

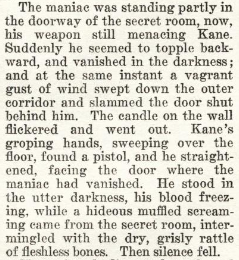

Johnny sees all this and just starts swimming. He’s in the water, which is all lit up from the phosphorescence in the water. This enables him to see something even stranger than just a Big Frog:

“…tucked like a stolen baby” is a a phenomenal line, isn’t it? The whole scene is really strange and evocative – the Frogfather has built a little house down there out of tree trunks, and the weird glow is coming from inside his lair. And, rather than simply gulping down Cuff, he’s swimming away with him into that glow, towards a fate that is implied to much weirder and worse than simple death. That’s great stuff, man, real weirdness here that you might not have expected from a simple Big Frog monster.

Johnny is swimming to safety when he hears a strange whistle, and something dark and swift suddenly bears down on him as he’s treading water…it’s the nameless old Indian, this time in a canoe. He helps Johnny into the boat and lets him gather his thoughts before they talk.

Another nice little glimpse of weirdness there: Frogfather would “have a way to deal with” a lot of people, if they were to go in there and try and do something about him, and buddy, you don’t wanna see what that would be! It’s another well-executed classic bit of weird fiction, where there’s a *hint* or something much stranger at work. Some dude comes in and starts killing frogs where he isn’t supposed to, well, that calls for the Frogfather just comin’ up and grabbing the guy. But a more complicated kind of incursion, with more people and boats and suchlike…well, that would mean the Frogfather would be forced to do something a bit more dire. Great, great stuff.

And that’s the end of Manly Wade Wellman’s “Frogfather!”

I love a good comeuppance story, and Wellman sets Cuff up as the perfect asshole – vindictive, cruel, sadistic, and totally uncaring. This is also a VERY short story, an efficient weirdness delivery system that sets up the scenario, executes its monster, and gets it done, all in a handful of pages.

It’s also interesting as a bit of eco-horror. Cuff is an exploiter of nature – he leads hunting and fishing trips for rich out-of-towners, explicitly the sorts of people who don’t need or appreciate the wilderness, but rather just use it for their own entertainment. Hand-in-hand with this is Cuff’s exploitation of his neighbors and fellow swamp folk – Johnny is an indentured servant, working to pay of his aunt’s debt to Cuff, and the nameless Indian is the definition of exploited labor, an oppressed minority barely scraping by on whatever pittance Cuff is paying him. All of this is in play when the Frogfather makes an accounting of Cuff’s many sins.

Now, speaking of the “nameless Indian,” I do think we have to unpack the racism going on here. This is 100% the kind of “mystical Indian in tune with the rhythms of nature” bullshit that is, unfortunately, still really common to see today. I mean, this guy doesn’t even get a name, he’s so primal and wise and mystical. He’s also just “an Indian,” a kind of undifferentiated and vague “other” that belongs to a different age. Combine that generic bullshit with the honestly very bad fake Indian name of the Frogfather, you end up with a sort of icky paternalism that just feels bad. I mean, at least he can use pronouns and doesn’t talk like Tonto, right? But even there, the fact that he’s better spoken than either of these (presumably) white characters is another part of that myth-making, part-and-parcel with his humble mien and deep-seated wisdom.

That said of course, the ending is great and fairly radical for the era – the idea that these stupid white people can’t handle themselves in the wilderness, even when told to their face what dangers there are out there, is satisfying, as is the explanation that they’ll have to come up with a lie that the white people will believe with regards to Cuff’s disappearance. This is a fairly common thread in a lot of Wellman’s fiction, the idea of indigenous or folkloric knowledge as fundamentally valid and valuable and deserving of respect.

I also like the setting – there’s plenty of backwoods, southern stories in Weird Tales, but the majority of them are honestly just using it as an “exotic” or (morally and geographically) remote locales, or, worse still, as a chance to indulge in some chicken-fried dialog. But Wellman, similar to REH and his Texas tales, has both experiences with the setting and a real affection for it, and that shows in his stories. Cuff isn’t just some dumb hick we’re supposed to laugh at; he’s an evil bastard, and it’s for that, his EVILNESS, that he’s punished.

Anyway, I like this story. Wellman, like I said, was a PROLIFIC writer and worth chasing down if you’re interested in this era of weird fiction and fantasy. He was an influential figure too, with a long shadow on the shadow, and he’s worth reading for that fact too. I’d stay away from the Africa stories; frankly, they’re a little rough, and while he DOES have an affection for the setting and history of the continent, he’s not equipped to really dig into it or approach it correctly. It’s his Appalachian stuff that’s most worth reading, both because he’s a better writer by the time he gets around to it AS WELL AS because he really DOES approach it in a way and with a style that you don’t see much of. Read the Silver John stories, at least; you won’t be disappointed!