(I jump right into my musing on the history of sci-fi mags in this one, so, just for ease, here’s the link to a pdf of the the issue that includes the story we’re talkin’ ’bout today!)

Leapfrogging out of the early 20th century (the GOLDEN age of the short story) and into the rusty iron-age of the almost-80s might *seem* like a mistake, but there’s still some fun to be had examining these late-era descendants of the pulps. Now, for sure, gone are the wild, heady days of a newsstand loaded with magazines of any and every genre imaginable (and a few you wouldn’t ever have dreamt up). The pulps’ decline began in the 40s when they were brutalized by WWII paper rationing, but the era really truly ended in the 50s when television rose to supplant reading as a primary popular leisure time activity. But a few mags held on somehow, and, much like their ancestors in the good ol’ days, they often record some interesting changes in the ol’ zeitgeist.

In particular, science fiction (which, antecedents aside, had been truly invented in the magazines) had developed a thriving enough fan culture that, here and there, a few prestige magazines had managed to survive and even thrive. These are, of course, Analog (formerly Astounding Science Fiction back in the good ol’ days) and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (founded in the 50s, and hugely important to the history of sf), both of which you can get a rejection from today, if you wanted. These (along with Galaxy) had become in some ways *the* flagship publications of the genre, a kind of “professional journal” for the convention and fan societies that had evolved out of the original pulp magazine letter pages and fandom.

And that fandom had entered a new phase of growth, especially in the shadow of Star Trek. Following its cancelation in ’69, there was a real hunger for sci-fi out there – Trek conventions had exploded, and there was a general paperback renaissance in genre fiction going on. There was also a flowering of the sort of amateur press that had led people like Lovecraft and Ray Palmer into writing/editing careers, this time in the form of Zines. Simultaneously there was, in the 60s and 70s, *also* an explosion in Fantasy literature, largely ushered in by the unauthorized Ace paperbacks of The Lord of the Rings trilogy in ’65. A similar Sword & Sorcery revival followed, fed by publishers trolling the pulp catalogs for fantasy stories and rediscovering Robert E. Howard and his many imitators.

The point of all this is to say that, by the mid 70s, there was a major genre fiction revival going on, such that the publisher of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine (two other magazines you can ALSO get rejections from today!) felt that there was room for another sf mag out there. This publisher, Joel Davis, approached Isaac Asimov about possibly lending his name to the endeavor, which, after some wrangling, resulted in the creation of Asimov’s Science Fiction (which you can…etc, etc).

Now, like I said, simultaneous to the sci-fi revival of the 60s/70s, there was *also* a revival in interest in fantasy around the same time, lead by figures with feet in both camps, like Poul Anderson, Andre Norton, the evil Jerry Pournelle, and the truly vile Larry Niven – these folks wrote both science fiction as well as fantasy/S&S, and were important figures in the Society for Creative Anachronism and those scenes. And, of course, there’s the 800-lb Wookie in the room: Star Wars (1977), the foundational text of modern science fantasy adventure, had completely revolutionized science fiction and popular culture. What this meant was that there was both a readership for and people writing in a kind of two-fisted, adventurous style, often combining overt fantasy with science fictional elements (and vice versa). Recognizing that this was an underserved market niche, Davis went about creating a magazine to fill it, and thus in 1978 was born the extremely short-lived magazine, Asimov’s SF Adventure, a sister publication to the heady, somewhat New Wave-ish Asimov’s Science Fiction.

That ol’ Isaac himself was a little ambivalent about this turn of events seems evident from the introductory editorials he wrote for the magazine. In the first issue, he gives a broad history of the “adventure” story, tying it back to the Iliad and the Odyssey, before leaping into the pulps of the 30s and 40s, trying to make an argument that *actually* that kind of red-blooded storytelling is an important and deep-rooted part of fiction. Later, in this the second issue, he argues that SCIENCE itself is the greatest adventure of them all…it’s all very unconvincing, and you’re left feeling like ol’ Asimov is mostly trying to make a purse out of a sow’s ear, at least from his perspective. That said, they did at least give him a rad illustration for his pieces:

It’s possible (even probable) that Asimov might not have even known what stories were going to appear in the magazine when he wrote these pieces, so he can maybe be forgiven for his poorly disguised distaste of the “adventure” tale. After all, most of his career had been spent advocating for a very “hard” approach to sci-fi, and his more “adventure” style writing (like his Lucky Starr books) had been published under a pseudonym and clearly aimed at younger audiences, a kind of entry-level sf meant to introduce the genre, rather than typify it.

But, all things told, I think the stories in Asimov’s SF Adventure are pretty decent, some good even, all mostly done by good (and occasionally great) writers. If anything, I’d say some of the offerings are actually too conservative. Most are very conventional examples of science fiction – they’re often very staid in their mingling of adventure writing with sci fi, adding a drop of fantasy or derring-do here and there into what are for the most part extremely traditional science fiction plots. It feels like they kinda throw the baby out with the bathwater in their attempt to avoid become TOO space operatic, you know what I mean? But, like I said, there’re some fun ones in here, AND I also think they reflect a kind of interesting moment in the genre, and are worth examination for that reason too.

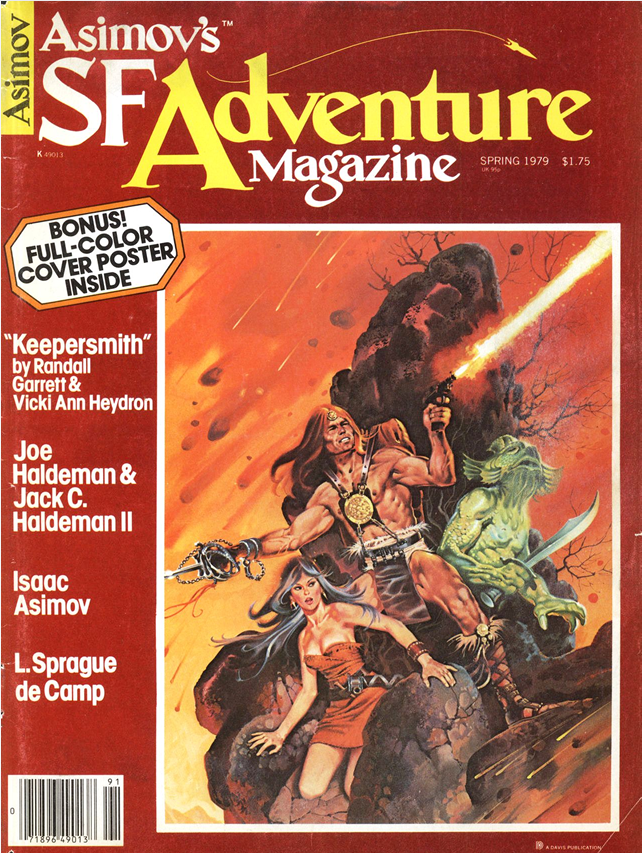

Anyway, yeesh, let’s get to it already: “Keepersmith” by Randall Garrett & Vicki Ann Heydron, from 1979! And look at this cover!

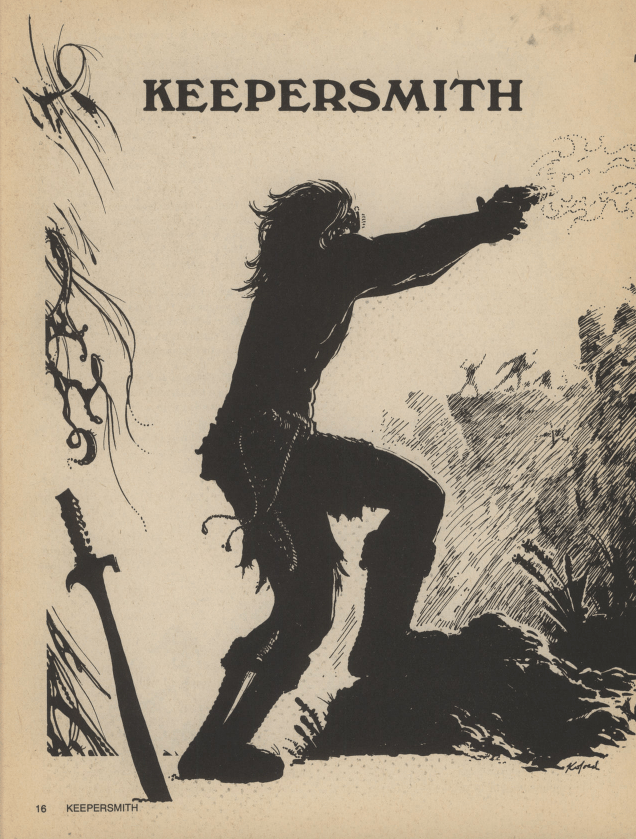

He-Man duel wielding a sword and blaster, some kinda fish guy warrior, a winsome lass, all in a chaotic wild landscape with rocks and ash/sparks flyin’, thrilling stuff huh? Honestly wouldn’t mind the full color cover poster that was, apparently, included with this mag. And the rad illustrations keep on coming in the story itself! Check out the two-page spread the title-page gets:

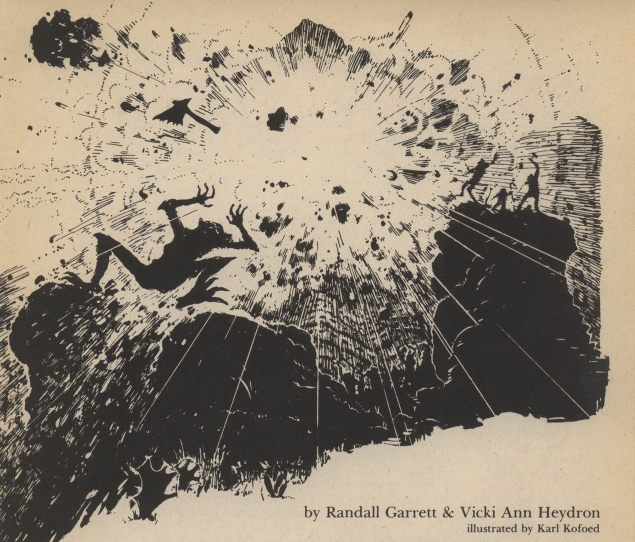

I like it – the stark black figures and landscape, with detail obscured, really conveys the power and brilliance of the explosion, and sword stuck in the ground while the obvious barbarian-type blasts away with some kinda superscience ray gun is a great dichotomy, really economical visual storytelling – the illos in this story are all by the great Karl Kofoed, perhaps most famous for his “Galactic Geographic” pages that appeared in Heavy Metal magazine, really wonderful work that you oughta hunt up if yer unfamiliar with it. He’s a great artist, and does some nice work here in this story!

The story starts with that odd, italicized entry, like something out of an encyclopedia, describing obvious sci-fi stuff and giving us a glimpse into a world of militarized space warfare between human space navies and spooky evil “Snal-things.” It’s interesting how, at first blush, this basically gives away the game with regards to the story’s plot, especially once you hop into the obvious fantasy-flavored stuff that follows – now we’ve got a weird-named guy with a big muscular body, the obvious product of physical hardship, all written with the kind of portentous tone reserved for fantasy adventures (particularly the capitalized “Man,” obviously meant as a species or racial designation). This is done very deliberately, of course, and I’ll have more to say about it later.

But lets move on! Keepersmith, our big Man, meets some people outside of his Keepershome where, presumably, he forges his Smithswords…stay with me, we get most of this Capital-Letter Noun Fantasy stuff out of the way early on here, I promise. Anyway, Keepersmith is goin’ on a trip, and not merely one of his usual jaunts – he “may be some time” as it were:

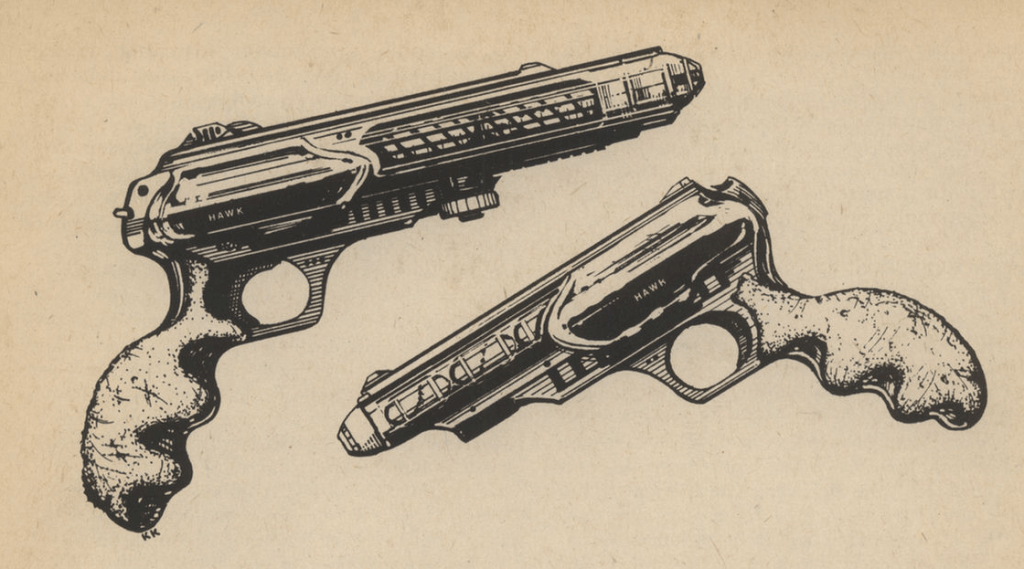

The three people Keepersmith has summoned are obviously troubled – this guy is clearly their leader, or at least in a position of authority, symbolized most strikingly by him being allowed to wield what is clearly a sci-fi ray gun, something that lets them “draw iron from stone,” an obviously useful trick in their otherwise barbaric world. They even ask him to leave Ironblaster behind – there’s just the one of it, after all, and without it they’d be unable to get more iron. But Keepersmith is adamant – he’ll need it on his journey. With his stern eyes slitted against the sun, he bids his friends farewell and begins his mysterious journey. It’s all very much the sort of barbarian heroics you’d expect from a sword & sorcery protagonist, isn’t it?

He travels all day and into the night, and we get some more world-building – there’re weird trees we’ve never heard of, and we’re told this place has a double moon, all background flavor that lets us know we’re on an alien world as well as getting us in the right mood for the story. Later, around midnight, he comes across a flickering fire, and sees the strange creature that kindled it:

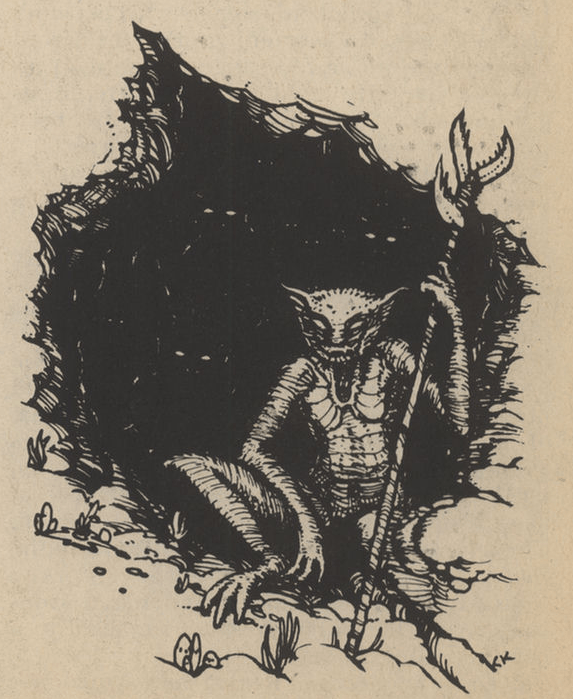

Every good fantasy adventure needs a Weird Little Guy, and this is ours – Liss, who we quickly learn is a scaly semi-aquatic being called a “Razoi,” natives to this world who have a contentious relationship with the Men (meaning humans; again, we’re in Fantasy Adventure Mode, so you capitalize it for the whole species, like in Tolkien).

We’ll learn more about Liss and the Razoi later on – right now we’ve been shown that it was the humans who taught them the use of fire, and that Liss knows Keepersmith personally. It is, in fact, Liss who has caused Keepersmith to begin this adventure, because he’s found something truly portentous…

The thing that’s summoned Keepersmith southward is the discovery of another, though slightly different, ray gun, stamped (we learn) with “I.S.S. Hawk” on its butt. It was Liss who found this gun; we’ll soon learn he picked up from the body of an enemy Razoi from the south. Liss is excited about this because he absolutely knows what Ironblaster does, how it’s used, and the importance of it to the Men. Keepersmith is also nonplussed by the weapon, although his expertise lets him see that it is actually different, perhaps most strikingly in that this blaster has those two weapon settings on it.

It’s a fun, sci-fi reveal, and it leads into a long block of exposition as Keepersmith and Liss both discuss this new, second blaster, and what it means. But, more importantly, there’s a bit of exposition here that fills out the very important relationship between Liss and Keepersmith, something fairly atypical between the humans and the Rozoi.

This is the heart of the story, and we’ll be coming back to it later. As a boy, and with no inkling of his future, Keepersmith was approached by Liss, who made a semi-prophecy about them and then, basically, proceeds to suggest what amounts to a secret treaty of exchange for peace between the Rozoi and Men in the mountains. Liss wants to learn, and he knows that the secret knowledge kept by the Keepersmiths would vastly improve his people’s lives. And, aside from the political/diplomatic connection that Keepersmith enjoys by having a rapport with Liss, there’s something else deeper there too:

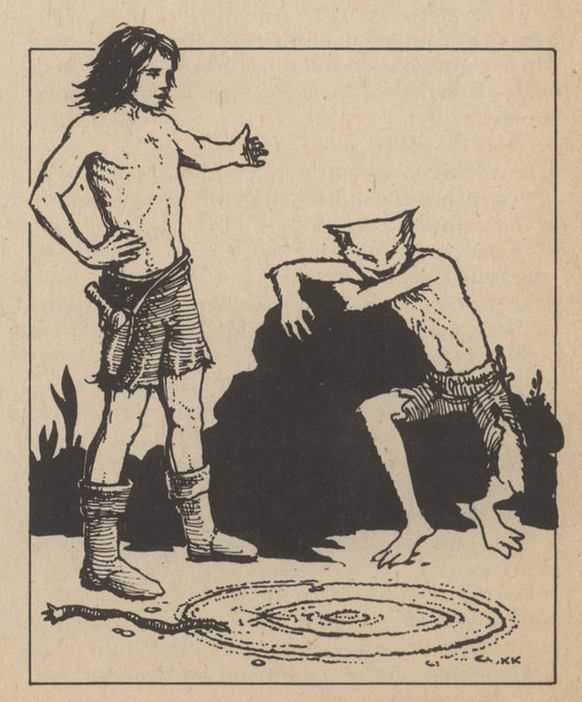

This friendship between Keepersmith and Liss is the heart of the story, and is what makes this an interesting piece. It also provides a prompt for a fun bit of art of the young Keepersmith and Liss:

This background of companionship and alliance explains why Liss 1) recognized the gun as important and 2) brought it to Keepersmith. And it provides a chance for Keepersmith to explain to Liss (and us) the history of Men on this world, and what the gun means.

We learn that the humans have a long and violent history with the Rozoi, first with the southern “dusteater” tribe, and then with Liss’s own northern tribes – there was, basically, a war, where the humans displaced the Razoi and forced them into new valleys up in the mountains – this much is remembered by the Razoi, who have an oral tradition of it, but Keepersmith proceeds to fill in the blanks.

Among the humans, there’re multiple traditions of what the “Hawk” is, but Keepersmith knows the truth – a long-ass time ago, and for mysterious reasons, the Hawk, a spaceship, landed on this world and left a bunch of humans behind, promising to return at an indeterminate time. There would be a signal from the ship when they were to return, and everybody had to be ready to go when it was received. Perhaps this gun is the signal?

Liss leads Keepersmith south, and while they travel for days and days and days, we get a little more exposition that fills in the history of humans and Razoi; we learn about the early trade networks that allowed the humans to survive, and the fact that Ironblaster has allowed them to not only defeat the southern Razoi but also dominate the northern ones. Here we learn a little bit more about what Ironblaster is: it’s a long-range weapon, too dangerous to use up close, that has been adapted by the humans for use in iron extraction. It is also the only remaining example of the Hawk‘s technology, which is (again) why Keepersmith is so interested in this new, second blaster.

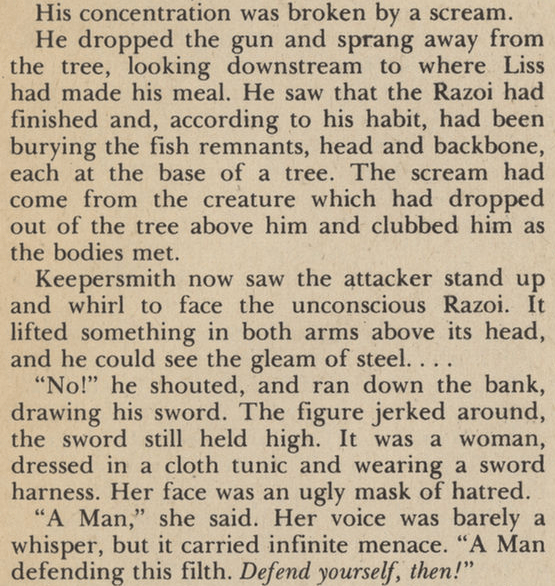

We get some techno-exposition too, with Keepersmith secretly dismantling the guns to compare their inner workings, showing that the traditions of his barbarian people run pretty damn deep, actually. But his Sally Struthers’ Gun Repair course is interrupted by a scream!

There’s a fight, and the outcome in anything but certain for Keepersmith – this woman is tall, tough, and clearly skilled in swordplay, and he has a very hard time defeating her. She expects to be killed and meets her fate with defiance and bravery, but of course ol’ Keepersmith merely tells her to sit down and not move while he checks on his friend.

We learn that this woman, Marna, has suffered a recent tragedy. A band of southern Razoi attacked her homestead, killing her husband and little child while she was out; there’s a particularly tragic scene where her kid, six-years old, is found in the dead in the doorway, with his wooden practice sword in his hand. Grim stuff! And it’s why Marna went a little crazy, hoping to get some revenge by killing as many Razoi as she could. Liss is incensed that he was mistaken for a southern dusteater, his own peoples’ ancient enemy. Marna seems unsure of Liss, but her reverence for the Keepersmith, who speaks for the Hawk, leads her to promise to never to harm Liss.

She accepts some food from them and goes to bathe in the stream, and while that’s happening Liss is dismayed to see the “broken” blaster that Keepersmith has disassembled.

What follows is a pivotal scene, a key development that makes this story interesting and worthwhile, and which will be built on later. Briefly, Liss is finally fed-up enough to call Keepersmith on his bullshit. He wants to learn stuff, but the crumbs that his friend Keepersmith has been handing out aren’t enough – fire is nice, but goddammit they want pottery and steel and, even more fundamentally, Writing, which would let them pass down their knowledge in the same way as the humans have done. Keepersmith, who we’ve seen is aware of all this, feels bad and, truthfully, doesn’t have an answer to the accusation, because that is exactly what he’s been doing. Humans have been hording their knowledge as a means of maintaining their power on their home world. Now, confronted with the fundamental unfairness of this disparity, Keepersmith is forced to make a decision.

Importantly, Liss keeps pushing. What if the humans DON’T end up leaving – will Keepersmith STILL keep the knowledge Liss wants for his people secret? Keepersmith squirms a bit – he feels like he can’t make this decision for all humans, that the riddle of steel is one he must consult with the others about, but he vows to teach Liss the secret of Writing, at the very least.

Keepersmith and Liss are joined in their quest by Marna, and they trio continue southwards. While journeying, Marna has some character growth and realizes that Liss isn’t the monster she thought he was, seeing him for the first time as a person, like her (the dusteaters, of course, remain monsters to be slaughtered by both of them…baby steps, right?). Later, there’s a thrilling battle scene where the three of them are ambushed by a bunch of dusteaters; this one is likewise a close battle, with Keepersmith coming close to being killed, saved only at the last minutes by the intervention of Liss and Marna. When the dusteaters try to escape, Liss pursues them into the river, bringing back a captive, which, it turns out, was his plan all along:

Solid fantasy badassery from Liss here, for sure!

The three are led to a rocky series of cliffs and valleys by their prisoner (who is promptly killed by Liss), and the three realize they’ve come across a major village of the southern Razoi. There’re caves and ridges full of ’em, and Keepersmith reckons there’s hundreds of them living here. Some good art, too!

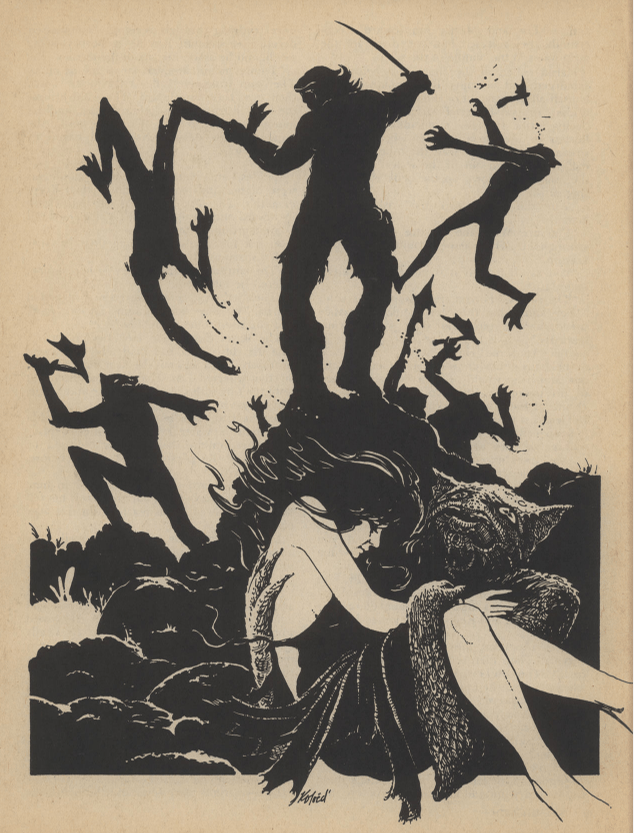

Some good, creepy cave-dweller shit in that illustration, huh? Really makes the Razoi look great and menacing, too. Anyway, Liss points up to a particular cave, high up on the ridge, and explains that, according to his information, there’s an entrance to an “iron room” where the smaller second blaster was found. I’m sure by now you’ve figured out where all this is going, but it’s still fun, nonetheless, and besides, we’re not given much time to think about it, because the trio have been discovered! Marna takes a sling bullet to the noggin and is knocked out! Keepersmith draws his sword and Ironblaster, and Liss carries Marna to safety. The scene is captured in some fun art too, although I wish Marna hadn’t been taken out of the fight so soon – as established, she’s a badass too, and it would’ve been fun to see her chops some heads with the boys, you know?

BUT, what we do get is Liss upgrading his weapon with Marna’s sword, and it IS pretty rad. He’s been studying the way of the blade on his own, it seems, in preparation for one day actually getting to hold a steel weapon.

As established, Ironblaster is no close-combat weapon – it’s too powerful, and at short range would be just as dangerous to the wielder as to the target. Keepersmith puts some distance between him and the southern Razoi, pops the goggles on, and then decides on a desperate and terrible action. Rather than blasting the fighters, he aims up towards where the iron room is, blasting away with the super weapon at the very walls of the valley itself. The terrible power of Ironblaster is on display, some kind of high energy atomic ray that, with blinding ferocity, destroys the cliffs and buries the southern Razoi beneath a zillion tons of exploded rock. The reveal of the blaster results in some good writing here too – the description of the “black sun” crawling up the surface of the rock is great, very evocative of unfathomable atomic power, you know?

And what (besides mass murder of the Razoi) is the result of this awesome display of super science power?

That’s right – exposed by the weapon is a huge metallic surface, the outer edge of some vast structure that was hidden beneath the rocks. Keepersmith knows that this was the mystery he had been sent to solve, and he proceeds alone up the cliff and into the metal thing, the door snapping shut behind him with terrible, grim finality. Liss and Marna know that they can only wait, and watch…

Three days later…

dun Dun DUN!!

I mean, it was pretty obvious, wasn’t it? Not that I mind, of course, especially since that’s not the point of the story at all. But we learn that, of course, this warship came to this world, some soldiers debauched, and while they were away on recon or whatever, a landslide buried the ship. The survivors of the expedition, those who had been on walkabout, just assumed that the ship had left and would, eventually, return, and so they passed down their knowledge and the story of the Hawk, in hopes that their ancestors would one day be saved.

And that’s the end of Keepersmith!

It’s a fun SF Adventure tale for sure, with all the fun super-science+barbarian stuff the genre promises, of course, and the characters a pretty good too – I like Liss, I like Marna, I even like the unflappable Keepersmith, honestly. And sure, the plot itself is telegraphed right from the get-go, but who cares? Because that’s not what the story is about!

I think Keepersmith is a really well-done narrative of decolonization that, importantly, moves beyond the very simple (and fairly common) “oppressor vs colonized” stories. Often, decolonization is portrayed as a simple and outright rejection of everything that the colonizer has brought. You often see this in “decolonize the sciences” movements, where nothing less than the total rejection of western scientific knowledge and practice is to be accepted; this, of course is stupid and destructive. Decolonization is not a return to something old. It is the creation of something NEW, a rejection of bias and oppression and unfairness in favor of partnership and alliance and cooperation, and that’s something very hard and much more necessary than a what a lot of these sorts of stories tend to portray (or people in the real world pursue, honestly).

Keepersmith’s journey to this understanding is really interesting and satisfying, I think – he begins with a sympathy and affection for Liss, after all, but he’s still not internalized the desperate desire of Liss to learn more, not does he understand *why* Liss needs to know more. When he’s later confronted with that (after the fight with Marna), his resolute and hide-bound beliefs begin to crack, and he realizes that there is a reciprocity that he needs to honor. But then, at the end, when he realizes the truth, that Man (as a species) is NOT leaving, that they are now going to LIVE on this planet and are a part of it, he comes to the much greater conclusion that the isolationism and hording that his people have been engaged in is not only wrong, but counter-productive. Liss and the Razoi (at least the northern ones…) have to come together to make the world a better place, as brothers (and sisters).

Now, of course, there’s plenty to be critical of here – certainly a bit of saviorship on display here, and similarly, you can ding the story for the fact that it is only the “right type” of Razoi that Keepersmith is extending the grip of comradeship to…but still, for a story from 1979, it’s a fairly sophisticated and nuanced approach to the subject, and one that rejects supremacy for equality, since it is EVERYONE who will have to learn new and difficult things. In particular, I’ve come across a lot of modern sci-fi where this kind of difficult, complicated conclusion would never be reached; for instance, how many “solarpunk” stories are just brutal eco-fascist fantasies of violent retribution? Here, Keepersmith realizes that Liss was right, that he and his people were wrong, and that CHANGE and equal partnership is the ONLY way forward. Pretty good stuff in my opinion!