Since I broke the (cursed Lemurian) seal on it, why not continue to plumb the depths of Swordly & Sorcerous fiction that appeared in Weird Tales in the years immediately following Howard’s death? We talked Kuttner and Elak last time, focusing on the differences in character and approach between ol’ Hank and REH, so this time we’re going to look at an example of Post-Howard S&S that adheres a bit closer to the formula perfected by ol’ Two-Gun Bob. It’s Clifford Ball’s “The Thief of Forthe” from the July 1937 issue of Weird Tales!

Interestingly, Clifford Ball’s first appearance in the magazine wasn’t as a writer, but as a Weird Tales reader mourning the loss of Howard and the stories he’d never write. His letter appeared in “The Eyrie” letter section of the January 1937:

This is only one of many such letters sent in to the Unique Magazine following Howard’s death (as I’m writing this, I think I might devote the next entry here on the blog to those letters, so stay tuned!); what’s interesting about Ball’s is that it really seems like the End of Conan struck him so deeply that he decided to try and Do Something About It – namely, Clifford Ball went and wrote some Sword & Sorcery himself! What’s more (and much like Kuttner), Ball also appreciated that one of the Keys to the success of Howard (and Conan) was the establishment of a fun, living secondary world – for Ball, this is (for lack of a better term) Ygoth, which is either a city or a country (it’s not exactly clear), and which is mentioned in all three of Ball’s S&S stories, tying them all together into a loose, unrestricted canon, much like Howard’s Hyboria.

Ball’s first story, “Duar the Accursed” would appear in the May ’37 issue; it’s an odd little work, very Theosophical honestly, about an amnesiac mightily-thewed barbarian hero who had been a mercenary, become a king, lost his crown, and then become a wanderer. There’s some interesting weirdness in it – in addition to having no memories of his early life, Duar’s accursedness is manifested as terrifying rains of blood and an ominous, unearthly raven that heralded his army. We’re also introduced to a strange, shimmering, extra-dimensional spirit that follows Duar and provides him magical support (whether he wants it or not), and has some kind of relationship with him from the past. There’s suggestions that Duar is himself some sort of Ascended Being trapped in a fleshy prison. It’s all very cosmic and, like I said, Blavatsky-ian; there’s pretty heavy foreshadowing that Duar is a kind of recurring spirit reborn as a hero or champion throughout time. But it’s also very much in keeping with Howard’s idea of the Manly Ideal of a S&S Protagonist – confident, physically powerful, fearless, and not interested in the niceties of civilization. There’s some good Gygaxian D&D flavored stuff in it too – the MacGuffin is a jeweled rose that’s actually a demon, and there’s a weird “Force” at work that drives people to their deaths in the depths of a dungeon. If you’re a completist for this sort of thing, it’s worth a read, but Duar never shows up again.

Ball thankfully (and correctly) drops the hints of “Chosen One” bullshit from his later (and last) two S&S tales, the much better and more fun Rald the Thief stories, the first of which we’ll be looking at today. But you should definitely temper your expectations here – they’re perfectly fine C-level work, I’d say, pastiches of what Ball obviously loved about Howard (and weird adventure writing), the sort of stories you expect from someone early in their writing career and looking for their voice. Unfortunately, Ball never got that chance – he wrote three more stories, though these are more straight weird fic than S&S. The last of these, a werewolf tale, was published in ’41, and then it appears Clifford enlists in the Navy. He ends up dying in, apparently, an accidental drowning in ’47, never having written anything else. It’s sad, especially because I think he had at least a sincere love of S&S, as I think you’ll see in the story today.

So let’s get to it already, sheesh:

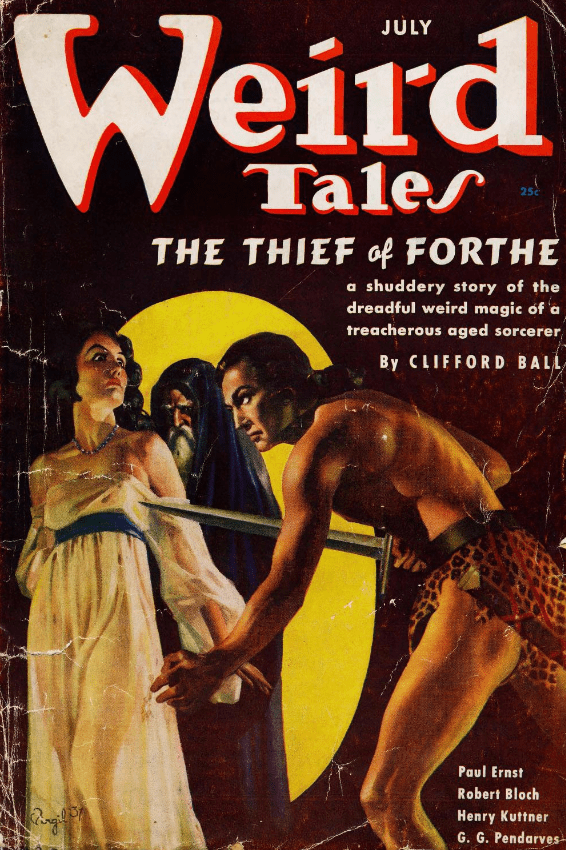

That’s right, Rald the Thief gets the Finlay cover treatment, quite remarkable and, much like the Elak covers, it speaks to the deep love that the new and as-yet-unnamed genre of Howardian-historico-fantastique-adventure tales had garnered. The iconography is interesting here, and gets to the heart of the appeal of these stories – a sword, a Man of Action, a damsel, and a mysterious threat. There’s not even a real background – the whole scene takes place in an indistinct void, really highlighting that the whole thing is a very literal psychodrama. Simple, but effective!

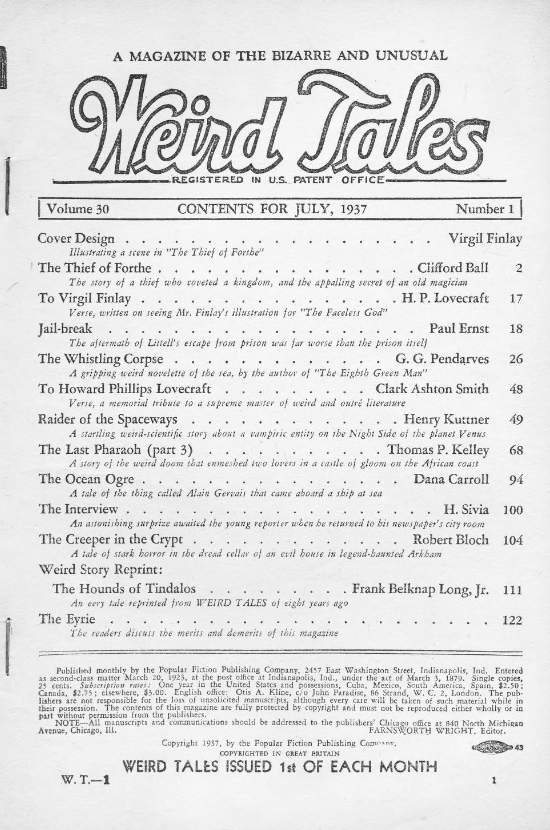

A good ToC, including a reprint of what’s probably Long’s most famous story, “The Hounds of Tindalos.” Also worth noting is CAS’s memorial poem to HPL, who had died in March of the year. It’s been a rough few years for Weird Tales fans, who’ve lost some giants in quick succession! Anyway, on to today’s tale!

A pretty straightforward summary here, and truthful too – this is a brisk tale indeed, rolling along at a decent clip with very little downtime. Case in point, our story opens in medias res, with a business meeting happening in a dank, drippy, disused dungeon. Two figures are conversing:

We’re introduced to a wizard with an apparently top-notch moisturization regime – their slender womanish hands a sure sign of sorcerous puissance and subtlety. This is in contrast to the other as-yet unnamed figure, who is immediately portrayed as a forceful, man’s-man kind of dude – he grumbles, he strikes the table with a meaty fist, and he’s suspicious of all this wizardly bandying of words about the King, named (oddly) Thrall. Yes, these two are surely quite different from one another, so much so that we get two more paragraphs describing them. First, our wizard:

Good, strange wizard physiognomy, I think, and the insanely hairy face is fun (and, obvious) foreshadowing of something. The “what’s under those robes!?” is a little thickly ladled on here, but honestly it’s not too bad, and it’s perfectly fine to hammer it home given where the story will end up. “Karlk” is a decent evil sorcerer name too, I think, short and sharp and menacingly strange. All in all, a top-tier evil magician, I think. And what’s the beefy fellow Karlk has been talking to like, you ask? Well:

No mincing words here, this is just Conan. Naked and muscular in a loincloth and sandals, obviously of a kind with the Cimmerian, strong, violent, and cunning (as evidenced by phrenology). What is interesting is that Ball calls out Rald’s scars, which is a detail I don’t think I’ve read about in Howard’s loving descriptions of Conan’s rough-and-rugged body. Ball wants to highlight the history of macho violence embedded in Rald’s body, because this, along with his near-nakedness, muscular bigness, and clean-shaven face, marks him as diametrically opposed to Karlk the Magician.

There’s some fun back-and-forth arguing between Rald and Karlk about King Thrall; Karlk seems to have it in for in him, but Rald points out the King has done alright by Karlk, covering up a mishap when one of Karlk’s “experiments” escaped. All in all, Rald seems disgusted by the wizard and their planned treachery. I’m no business guy, but it really seems like at this stage of the negotiations (along in a dripping dungeon), you’d want to have this kind of stuff ironed out. Karlk seems put out by Rald’s apparent lack-of-fear; he is a weird, menacing wizard, after all, and is used to a modicum of cringing respect. So Karlk decides to show Rald some of his power:

And how does Rald react to Kralk’s laser beam?

I mean, fair enough, right?

Regardless, Rald wants to get down to business…what IS it that Kralk wants to hire him to do, anyway?

Rald’s professional pride is fun, as is his discussion of what the possible targets of his thieving might be. I like the little “No women, mind you!” bit too, it’s all very material and earthy, a lived-in detail that captures Rald pretty well and gives him a bit of depth.

That is solid wizard shit there, you know what I mean? Kralk is steeped in black lore, and has moved beyond mere jewels and such. Kralk wants Rald to steal THE VERY KINGDOM ITSELF!!!! which is so bonkers, I love it. Rald’s reaction is fun too – how can you steal a whole kingdom, particularly one which is, in some way, divinely ordained. King Thrall is the King of Forthe, simple as? How would Kralk take over, even?

Very fun stuff; Rald is thinking about the Realpolitik of Kralk seizing the throne of Forthe, how impossible it would be to hold it given how everyone hates and fears him, but Karlk leapfrogs over that problem by the simple expediency of having RALD be the king, with Karlk a hands-off power behind the throne. Rald’s realization, and the temptation, are handled really well; Ball has constructed a convincing web for his Prince of Thieves to get enmeshed in!

I love the whole “wizard practicing the blackest of sciences” angle to these early S&S stories – it’s something Howard did himself, with a lot of his evil wizards relying on drugs and alchemy and hypnotism more than thunderous bolts of power. Similarly, Kuttner had his weird little wizard Zend behaving more like a scientist, using occult forces and magic-technology to keep Atlantis from sinking, for instance. Karlk’s claim that they are merely a scientist is a lot of fun, and something that I feel like you don’t see as much of in fantasy these days – wizards are a lot more mystical and esoteric, which is a very different characterization from experimental and technical approaches to even blasphemous sorcerous knowledge.

It’s also menacing as hell, isn’t it? We had that little story about the dog-man thing that had to be executed after it escaped, a very strange and unsettling story, and Karlk seems to be mostly interested in being allowed to expand his research program, something that would necessitate a friendly king willing to turn a blind eye to whatever horrors he’s planning. Of course Rald is disgusted…but…

It’s a solid Faustian bargain – Rald puts up a good front, but he’s quickly broken down by Karlk’s tempting him with not merely wealth and power, but immortality as a dynast! It’s fun and unique, making Rald a bit darker and more morally ambivalent (for now, at least) than his literary progenitor Conan. The story is a bit grimmer and grittier too; Conan had lots of adventures motivated purely by greed, but he never stooped so low as to ally himself with an obviously evil wizard! Credit where credit is due, Ball has come up with a fun and novel plot!

The next section opens on Rald beginning his infiltration of the Palace of Thrall. There’s some fun world building in here, among some admittedly clumsy and overwritten sentences. The walls of the palace, both inner and outer, are crumbling and in poor repair, and the patrols of the guards are fairly cursory and easily evaded. Similarly, the jagged bits of metal embedded at the top of the walls are rusty and easily pushed aside. But most importantly:

That’s a nice touch, and conveys a lot about this place and its history. They don’t need to maintain the walls or a tight guard – the sanctity of the palace is exactly that: sacrosanct, the product of cultural and religious scruple that sees the King and his power as a holy, divine thing, which NO ONE in their right mind would ever violate! Luckily, Rald is free of such scruples. This is more than just a nice bit of flavor, too – it will explain what exactly Karlk’s plan is, and how a whole kingdom can be stolen.

There’s a really nice bit of writing around Rald’s skulk through the garden here:

The statue he mistakes for a person, and the annoyance of the wet sandal are great, nice little bits of very realistic detail that lend Rald some interiority as well as highlighting his real physical experiences sneaking through the forbidden grounds. Equally fun is the fact that Rald knows the layout of the castle absolutely, due to the simple fact that everyone does, from servant’s gossip. The way Ball tells us that the simple peasants would be horrified at the use their gossip is being put to is fun writing. There’s a lot of nice details in this story, I think, and Ball is very much taking his time trying to develop the scene and evoke the setting, and it’s (largely) paying off, I think.

Rald makes in into the castle and encounters a drunk guard and, in a room beyond, a sleeping woman whom he takes to be a courtesan of some sort. Finally, he reaches a door that, via the clarity of narrative convenience, Rald realizes must be his goal:

Might be a real “Marge_Potato.jpg” moment here, but look: I just think this is neat. It’s extremely fun that Rald is an atheist in a magical world with gods, and that it’s this atheism that allows him to lift the magically warded lockbar without being struck down by the mighty curse woven into its very matter. That’s good stuff, and it works nicely with the whole thing going on in this story – the decrepit theocracy being vulnerable to One Atheist Thief!

Rald pushes through the door and enters some kind of sacred council chamber where the King and his sister hold court. More importantly, there’s the sacred necklace that is the goal of his quest hanging there!

So potent a symbol is this necklace that merely possessing it makes one, functionally and practically, the ruler of Forte. It might seem like a goofy system of gov’t, but who the hell am I, an Amerikkkan, to judge? More importantly, it’s in keeping with the whole tenor of this country/city-state, right? This religiosity that seems to rule here would absolutely imbue an object, and whoever happened to be holding it, with absolute political power; it makes sense! And it seems to have worked out just like Kralk imagined it would…or has it!? For, while Rald is admiring the sparkle of the diamonds that make up the necklace, he’s interrupted by a voice!

Do I wish Ball had given Rald a better swear than “faith?” Of course I do. Do I love this mysterious person telling Rald to knock it off with all the jumping around like some damn ape? Absolutely. It’s funny! The whole thing is very swashbuckly, and I love it.

The newcomer is the King’s sister, the Lady Thrine (apparently a real, if rare, Danish girl’s name, by the way), and she’s aghast at the temerity of Rald to not only break taboo by touching (and proposing to steal) the Sacred Necklace, but also by DARING to enter her bedchamber and peer at her sleeping. Yes, she was the “courtesan” from earlier, and its the whole shock of the boldness of Rald’s crimes that have lead her here, rather than, say, calling out all the guard. There’s some flirty banter, honestly not badly done, particularly since Ball is working on his own here in a Pre-Mouser world, but it’s cut short by the sudden arrival of Karlk!

Again, it’s a really great part here that Karlk, a magician and therefore intimately familiar with the reality of occultic forces, couldn’t move the magical bar with its potent spell, so he hired an atheist thief to do it. That’s good, a solid interesting premise for a S&S story, and also an interesting “mechanic” (if you’re excuse the vulgarism) for a S&S world, where magical potency is in some way related to belief. It’s fun, and something you don’t see much of these days!

Anyway, Kalrk prepares to zap Thrine, something the besotted Rald CANNOT ALLOW TO HAPPEN…but it’s all put on hold by the arrival of King Thrall, in full battle armor. There’s a funny bit where Rald, again in Mouser fashion, asks exasperatedly “doesn’t anybody SLEEP in this castle?” which is a funny, solid joke for a S&S story. There’s more banter, some guards show up, and the Kralk and Rald are bound up with ropes. They’re left, unguarded, in the council room (with the necklace) while Thrall, having sent his sister back to her room, orders a quick search of the gardens, in case there are more conspirators. Left alone, Rald and Kralk bicker a bit, with Karlk realizing that Rald has scruples he hadn’t imagined.

And then Karlk does something weird:

Khalk unties himself with an extra pair of small, white furred arms that emerge from his robes! I mean, that’s absolutely great! Equally fun in the kind of nonchalance with which Karlk assures Rald that there’s a LOT about him no one knows. It’s a great scene, and very weird.

Also fun is how Karlk, while having to leave Rald behind, still proposes to honor their partnership – he’ll kill the people Rald can’t, and then Rald can become King, with Karlk the power behind the throne. It’s very logical and straightforward and, honestly, makes Karlk out to be even more inhuman and mysterious. Afterall, while he’s disappointed Rald didn’t just kill the Princess, he can still use him. It’s fun, weird, stuff, and honestly between that and the extra arms, Karlk is up there with the evil wizards in S&S lit, in my opinion.

Rald doesn’t waste time, however. After Karlk has left, he painfully hoists himself up, knocks a torch from its sconce, and uses it to free himself. In the corridor he finds a guard, horribly magicked to death by Karlk. Grabbing the dead man’s sword, Rald rushes down the corridor, hearing a woman’s sobbing scream of terror from somewhere ahead. Rald comes upon a deadly, dangerous scene – Karlk, crouched horribly over the bound and terrified figure of Thrine, preparing to blast the unsuspecting King Thrall with evil magic. Rald leaps into action, slicing into the surprised Karlk with his sword:

Thrine tells the king that Rald saved him, indeed saved them all from Karlk’s deadly magic, which the King grants, though of course he DID plan on seizing the throne himself. With a modicum of contrition, Rald foreswears his earlier actions:

Rald agrees that an evil, murderous wizard can never be a man, but hilariously he has misunderstood Thrine. For, in fact…

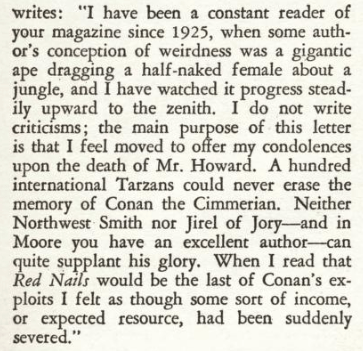

Karlk was a GIRL all along!!!! The fake beard, the scrupulous flowing robes, all a trick! But that’s not her only secret…

How came she to have royal blood, you might ask, and King Thrall certainly does. Well, it’s a funny story:

Kind of grim, and with an unfortunate amount of “monstrous ape rape” (a surprisingly popular theme in early Weird Fiction). Also, you might not recognize it, but the “white apes of Sorjoon” are basically the multi-armed white apes of Barsoom, from Burrough’s John Carter of Mars stories; in the earlier Duar the Accursed story, Ball refers to them as the white apes of the “hills of barsoom,” even. Maybe it was an editorial decision to change them, or perhaps he thought in hindsight that that was a little too on the nose. Still, everybody reading Weird Tales would’ve immediately recognized the Great White Apes for what the were, horrific multi-armed ape monsters from a classic swashbuckling sword-and-planet tale. It’s interesting that Ball uses them here; speaks to the importance of Burroughs for the readers of these more action-oriented, thrilling adventure weird tales, I think, and is in keeping with Ball’s letter eulogizing Howard too; he mentions “a thousand international Tarzans” as being unable to make up for the thrill and power of Conan, suggesting the lens through which he was being read, by some at least.

Anyway! Karlk’s extra arms come from her White Ape parentage. There’s a bit of Howard’s Atla in Karlk here too, from “Worms of the Earth.” Both of them are outsiders, cursed by their lineages to belong to neither of their parents’ worlds. Cursing all of mankind, Karlk devoted herself to evil and the eventual overthrow of Forte. There’s some great, creepy writing as Karlk’s laments her poor experiment back in her hut, and then she dies.

The story wraps up with a nice little bow – the King roars that, for his great deeds this night, he’ll make Rald a baron, but the thief is gone. But don’t worry, says Thrine, he’ll be back…for her!

And that’s the end of “The Thief of Forte!”

From a Sword & Sorcery perspective, I think this story is pretty decent. There’s good world building, and Karlk is a fun and interesting character that, honestly, I would’ve liked to spend more time with. Rald is basically and blandly a species of Conan, though maybe just that much more avaricious than the original – like I said, working with an obviously evil wizard seems a bit too much for ol’ Conan, though Rald readily agrees (even if he does have second thoughts later).

It’s not some lost masterpiece of the genre by any stretch, but it’s at least as good as Kuttner’s Elak stories, I’d say. What is interesting is that both of them, Ball and Kuttner alike, offer different perspectives of the post-Conan and post-Howard genre. Ball’s is much more straightforwardly a pastiche, I’d say, with Rald simply being Conan, or at least much closer than Kuttner slim and amoral Elak. Ball also seems interested in the women in S&S stories, more so than Kuttner at least; perhaps he’s influenced by Moore’s Jirel stories there, probably the most important non-Conan S&S character to emerge in the 30s. Ball has a bunch of tough amazons in the second Rald story, and there’s a pretty tough queen in the Duar story, though of course all end up conforming to comfortable 30s heteronormative roles by the ends of their respective tales. By far the most interesting character in Ball’s slender oeuvre is Karlk, though, and I think the story is worth reading for them alone!

Maybe more to the point, I think it’s worthwhile to read these attempts at carrying the torch forward in the post-Howard days of Weird Tales, particularly because they’re wrestling with something that would dog the genre well into today, namely: where do homage, tradition, pastiche, and out-and-out cribbing fit in the genre, and how do we push at the boundaries and make something new? Obviously there’s a deep love of Howard and his work here, but how do you build on it without simply (and more weakly) recapitulating the same tired old themes and plots and characters. I don’t think there’re answers in these stories, but I do think it’s fruitful to read them and think about these questions!