Gathered ’round the red glow of the fire at night, its feeble flame keeping wolves (and worse…) at bay while we discuss the weighty topic of The Pulps, one name looms larger than all others, a name of ancient renown steeped in glory and deep lore: the Man from Cross Plains himself, Robert E. Howard. And while I don’t want to get bogged down JUST talking about him, it is the fact that, in addition to basically creating the genre that Fritz Lieber would later name “Sword and Sorcery,” ol’ REH is also one of its indisputable masters, having written some of the best examples of the genre ever. So, while we ARE going to be eventually talking about OTHER people, there will be at least THREE of these pieces that focus on my fellow Texan, Big Bob Howard. And for today, that story is “Rattle of Bones” from the June 1929 issue of Weird Tales.

That’s right, we’re saving Conan for later and STARTING with Howard’s first indisputably successful series-spanning character, the two-fisted, sword-swinging, berserker-Puritan himself, Solomon Kane! I’ve always liked Kane (shame about the movie though…) and I think he’s an important step in Howard’s career. In addition to being a real recurring character, he also seems to have helped Howard crystalize some of his ideas about what he was interested in as a writer, per say.

But wait, I can hear you saying, didn’t I *just* say last time that sword and sorcery wasn’t created until the Conan story “The Phoenix and The Sword” was published in 1932!? What’s this 1929 story doing here in Sword and Sorcery month!? Read on, O Prince (or Princess, as the case may be)!

Leading up to this issue of Weird Tales, Howard was already an established writer: his first professional story ever was “Spear and Fang” from ’25 in Weird Tales, a lusty, action-packed caveman yarn that was extremely well-received. He wrote some more traditional, gothic-style horror tales, in particular “Wolfshead” in ’26, which was another huge success with the readers of Weird Tales and established him as a talent in Farnsworth Wright’s stable of writers. All of these stories are very much in the vein of Howard’s early horror writing, tortured protagonists struggling manfully against a hostile world full of occult threats, rich in historical (or prehistorical) trappings and settings. Importantly, he has introduced the Picts in “The Lost Race” from 1927; these dark, gnomish figures of a forgotten age who lurk in the twilight on the edge of our world are, for Howard, a synecdoche. They represent all of his literary preoccupations: civilization and barbarism, history drenched landscapes, violence, empire, decadence, atavism, and race. While these previous stories are very much still in the weird fiction tradition, focused on moody reflections of doom-laden fate and ancient knowledge, they are nonetheless grasping towards what would eventually become sword and sorcery, where weird horrors exist to be confronted rather than merely suffered. And Kane, as a brave and violent character that can appear in different stories and different settings over and over again, is an important part of bridging that gap from the early “weird fiction” Howard to the “blood and thunder” Howard that we know and love later.

That’s a long preamble, so we’ll save REH biography talk for later. Now, let’s take a look at this issue of Weird Tales!

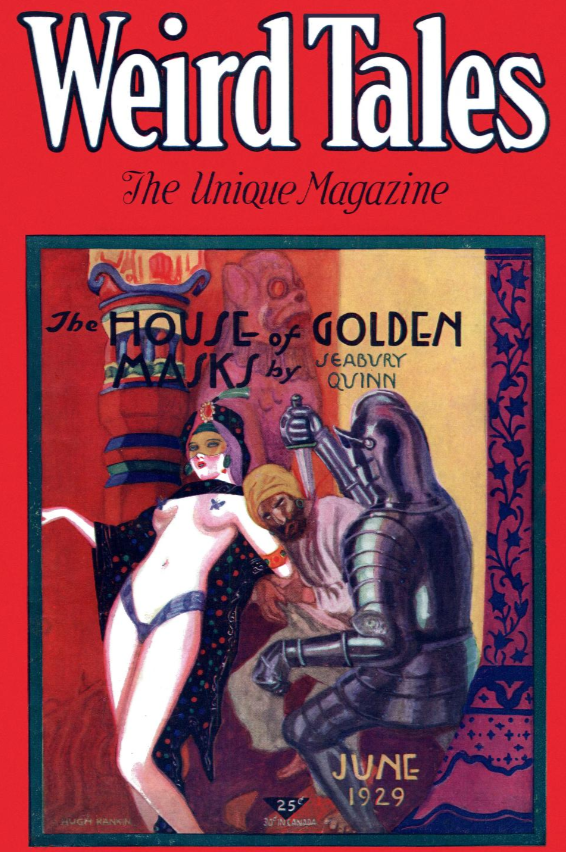

An excellent and very risque cover from Hugh Rankin, illustrating (vaguely) a scene from a Jules de Grandin story by Seabury Quinn. It’s got a great, almost art deco style cover to it, doesn’t it, and the nearly naked woman is particularly stylish and evocative (he said, looking respectfully). Probably way more interesting that the story it’s illustrating, I’m sure – Quinn was a HUGELY popular writer at Weird Tales, surpassing Lovecraft at this point, and his occult detective Jules de Grandin was one of the most popular characters in the magazine. The stories themselves are perfectly fine, but it’s always baffled me HOW bonkers people were for them back then. Changing tastes, I guess. Anyway, the ToC:

Not TOO much to write home about in this issue – Derleth and Whitehead are very much second-stringers in the Lovecraft Circle, and the big names at the time were definitely Quinn and Hamilton; they’re right up right up front in this issue, with a bullet. Howard is comfortably in the middle of the issue, and Wright took particular care to call out that “Rattle of Bones” is a Solomon Kane story; they’d given Howard’s first Kane story, “Red Shadows,” a cover earlier in 1928, and there’d been a second Kane story earlier in 1929, so they’re working hard to make sure people know that this is a recurring character. So let’s get into it, shall we!

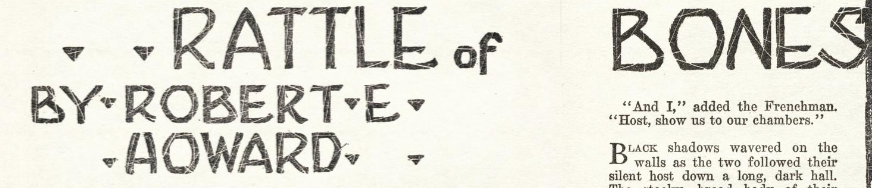

Unique typesetting on the title this time, huh? It spreads across two pages too, but there’s just one word over there on the second page, kind of spaced weirdly. The title font is only used for this story in this issue, which is interesting. Weird Tales was always financially strapped, generally just skating by, so I kind of wonder if they were trying to get some visual interest on the cheap here? But, that’s not to say that they couldn’t afford an illustration!

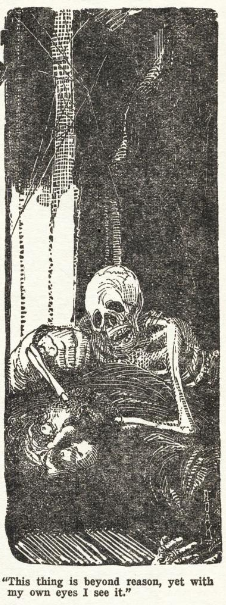

Ah yes, Weird Tales, the magazine never afraid to spoil a story with an illustration right off the goddamn bat. Of course, this one isn’t the worst offender, but still, c’mon ya’ll, let a story breath, would ya?

Efficient and evocative, Howard wastes no time here. Two men travelling through the dark, silent, shadowy black forest approach the Tavern of the Cleft Skull. The landlord is suspicious, and demands to know who these guys wandering the deep forest are. One is, of course, the English Puritan Solomon Kane, and the other is a Frenchman with the unlikely name of Gaston l’Armon. The sullen, suspicious, secretive landlord lets them in, and we get a brief description of our characters: Kane is a goth, all in black with a black featherless hat that sets of his pallid, intense face. Gaston is of a different sort entirely; he’s very much a French Poppinjay, all in lace and finery. And our landlord?

So he’s obviously a deeply sinister motherfucker, even without that last little “few come twice,” thing which, I mean, jeez man. Way to give away the game, although when you have two small red eyes that stare unblinkingly at people, maybe there’s not much dissembling to do? Kane and l’Armon finish up their meal and head on up to bed.

This is a pretty short story with pretty spare descriptions, but I think Howard uses his words to good effect here – the wavering shadows on the walls of the long dark hall and the broad, stocky body of the weird innkeeper shambling ahead of them…it’s a really nice picture, the sparse language helping to convey the silence and the stillness and the emptiness of the Inn of the Cleft Skull.

Inside their room, Kane notices that there isn’t a bar for the lock. There’s a bit of banter between l’Armon and Kane, and we learn that the two of them met by chance a mere hour before coming across this lonely inn out in the middle of the German black forest. Still, they decide that they might like to be able to lock their door, so they go out in search of a bolt in one of the other rooms. This trope of an inn as a trap, and in particular one where the trapping is done via locks (or the absence of them) appears in two other big famous stories. One is Howard’s Conan story “Shadows in Zamboula” from 1935 (a good but controversial story that showcases some of the worst of Howard’s casual racism) and, interestingly, it plays a major part in Lovecraft’s “The Shadow over Innsmouth” from 1931 (where it precipitates one of the few action scenes in a Lovecraft, actually). It’s an effective bit of horror stuff, though – vulnerable and unprotected in your sleep, not even a locked door between you and whatever threat is out there…it’s spooky stuff! Kane and l’Armon agree that they’d like to be able to lock the door, so they set off to search the other empty rooms of the inn for a bar to lock their door with. But, they find them all similarly unlockable. And then they come to the very last room at the faaaaaaar end of the dark hallway.

They find the Inn’s murder room which of course we were all expecting. Bloodstained floors, smashed furniture, and even a secret passage!

That’s pretty wild, huh? The inn keeper cleaves some poor bastard’s head clean through AND THEN chains up his corpse in a secret chamber? Confronted with the evidence of their murderous host’s past actions and his immanent threat to them, what do they do? They start screwin’ around with the skeleton, of course:

Perfectly normal thing to say, Gaston l’Armon, I’m sure it’ll have no bearing whatsoever on the rest of the story! But Kane has had enough; he wants to confront the innkeeper with the evidence of his crimes! He turns, preparing to leave, when the unthinkable happens!

Betrayed! And now Kane recognizes him…he’s Gaston the Butcher, a famously murderous brigand! He had planned to murder Kane in the night, the treacherous dog, but a chance came along and he took it! Now he’s going to kill Kane and take his gold. It’s a solid plan, simple and straightforward, and Kane seems to be facing his imminent death (and at the hands of a Frenchman, no less) when, suddenly…

That’s right! Looming up behind Gaston in the hallway, the inn keeper cleaves himself another skull, thereby saving (albeit briefly, as we’ll see) Solomon Kane’s life! By the way, the “hanger” that the innkeeper uses to chop Gaston’s head open is a type of sword, a very short sabre that was popular with woodsmen and hunters before making the jump to the navy and artillery officers of the 17th and 18th centuries. It’s called a hanger for the way it hanged from the belt.

Kane moves forward, but is quickly menaced back by the innkeeper, who has a long-barreled pistol in his OTHER hand. If it’s not one thing it’s another, you know what I mean?

First off all, the innkeeper is a nice and effective example of escalation, one of the staples of adventure literature. Gaston was bad, sure, but now Kane is face with a worse threat, a man driven to murderous insanity by the brutality of a Continental prison. The line, “And deep in my brain, the wounds of the years…” is really great, and it instantly turns the Host of the Inn of the Cleft Skull into something wilder and weirder and more tragic than a simple homicidal maniac. He’s been broken irrevocably, to the point that he’s now hiding out in the woods and waging a murderous war on all humanity. It’s great stuff, real dire threat.

But what, you ask, of sorcery? Well, there’s that strange sound again. Gaston had heard something scrabbling around in the chamber with the shackled skeleton, noises that Kane had dismissed as rats bothering dry bones. But the innkeeper has a different interpretation of the sound.

The madman continues with his ranting, explaining that the skeleton had belonged to a Russian sorcerer who had stopped at the inn and whom he had, of course, killed. But the wizard had vowed that his dead body would rise up and avenge him, so the Innkeeper stripped his bones and shackled his skeleton to the floor in the secret chamber. “His sorcery was not powerful enough to save him from me, but all men know that a dead magician is more evil than a living one,” says the innkeeper, sidling around to check on his prisoner.

I mean, that’s a great scene, isn’t it? A door to death yawning wide, then the man suddenly toppling backwards in a panic! A gust of wind that snuffs out the candle and shuts the door to the secret room where, sealed away, all Kane can hear is muffled screaming and the rattle of bones! Just top notch stuff, really simple and direct and effective. Kane kindles a light and sees a sight that horrifies him:

And that’s the end of the story!

So, first thing first, this is definitely a horror story, and not even a particularly weird one – there’s nothing cosmic or mind-bending about the monster here…it’s a wizard’s skeleton, and it literally just strangles a guy to death. In fact, the Innkeeper is a much weirder threat; he’s been brutalized so thoroughly that he’s lost all humanity, becoming an engine of destruction and murder who lays in wait for any and all who happen to come his way.

Similarly, the proto-sword and sorcery elements might seem to be thin on the ground here. Kane is mostly held at gunpoint the whole story, and he doesn’t even get a weapon of his own until the very last bit of the story. He doesn’t fight anybody or anything, and mostly just watches as the events of the story unfold around him. In fact, if you haven’t read the previous two Kane stories, you might be a little skeptical of the whole “Kane is a sword-and-sorcery hero” thing here (it’s much clearer in those stories, though – he’s sword-fighting and ranging all over the place in those, and generally a lot more active and dynamic than here, as well as menaced by sorcery and horrors).

But! I think that this story nicely illustrates Howard’s changing direction and the way he’s developing a distinct aesthetic. First of all, there’s an interesting use of the environment. The black forest setting is gloomy and threatening, and this ramshackle inn with a terrible name is, rather than a welcome sign of civilization in a wilderness, actually much wilder and more lonely than the woods themselves. The threats of the forest, wolves and weather and such, are after all natural, while the canker of the inn is wholly unnatural, a blight on the face of the earth. And the origins of that blight are sunk in the brutal degradation that Man visits of His Fellow Man, which is a very Howardian perspective that underpins many of the Conan stories.

You’re also beginning, I think, to see the tell-tale interest in the specific settings and materiality that makes for good sword and sorcery. Howard is always interested in making you believe that the places he’s setting his stories are real; now, that might be easier when the place IS real, like the black forest, but the work he’s doing is still substantial – after all, he’s just said “black forest” and “Germany,” it’s not like he’s providing an in-depth primer on the socio-economics of Baden-Württemberg. BUT I think there is an obvious interest in conveying that this landscape is real, and that the people and places in it are historically contingent. By playing around with those ideas in stories like this one, he’s practicing for the quick but evocative realizations that he’ll need to make Aquilonia or Turania seem like real places with real histories and economies and cultures, the sort of backgrounding that makes the Conan stories work.

There’s also a brutality to the characters that is interesting and important. The innkeeper, who is insane, is certainly a grim enough fellow, but Gaston’s depravity might be even worse. After all, the innkeeper at least has an ethos, man, but Gaston is straight up just a greedy murderer. Both of them have been degraded and turned into monsters, in fact; the innkeeper by a cruel and crude “justice” and Gaston by his own avarice. In the Kane stories, it’s implied that he is a volcanic, passionate man whose natural tendencies are kept in check not by his strict Puritanism but rather by his single-minded obsession with his own ideas of justice and righteous violence. In fact, over the course of the stories, you could very easily say that Kane is very similar to the poor mad murderous innkeeper, the only difference being that Kane’s endless war is being directed at the right people, brigands and murderers and inhuman monsters. That kind of psychological depth, and in particular the emphasis on the darker side of human beings, is certainly one of the poles holding up the sword and sorcery tent, and it’s in the Kane stories that Howard really starts to explore it.

I obviously really like this story – in fact, it might be my favorite Kane story. Don’t get me wrong, there’s good swash-buckling in a bunch of ’em, although you do have to prepare yourself for Howard’s paternalistic take on Africa for a lot of them (“Wings in the Night” is probably worth a read, though). And Kane is probably Howard’s first Great character, a dynamic and forceful and interesting personality, a Puritan who is, actually, a Barbarian hero, subject to gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirths. And while it’s short and Kane doesn’t get to do much in it, I still like the tone and mood of this piece – it’s a horror story, yes, much more so than sword-and-sorcery, but it’s almost there too, just teetering on the edge of a new genre. I think it really is a good key to understanding the evolution of Howard’s writing and thinking, and how all of, his interest in history and civilization and people, is going to blossom very soon into something special and epochal.