The Big Day is here: All Hallow’s Eve; Samhain; Satan’s Birthday(?); Pumpkinmas. Yes, it’s Halloween, and as is good and right, we’re celebrating the day with a particularly excellent story dissection/discussion/ramble – Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost” from the October 1941 issue of Unknown Worlds!

We’ve hit Leiber before, of course, discussing his very first story in Weird Tales (“The Automatic Pistol“) as well as the first Fafhrd & the Grey Mouser story in Unknown Worlds (“Two Sought Adventure“) so, obviously, we’re all huge Leiberheads around these parts, just absolutely Fritzpilled. He’s a great writer who had a huge impact across multiple genres – weird fiction, sci-fi, and especially in the genre he named, sword & sorcery. Immensely important figure, and a helluva writer too boot! And man, lemme tell ya – this story today is a killer!

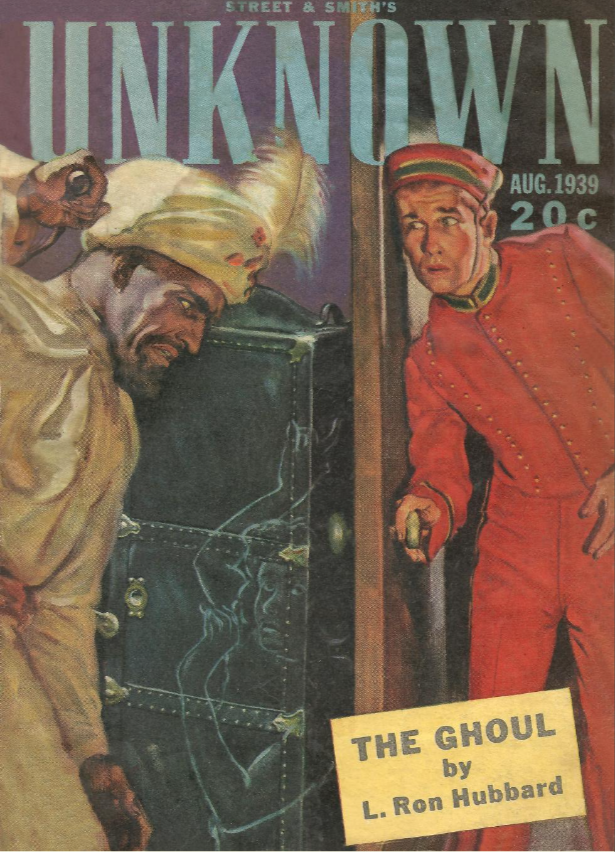

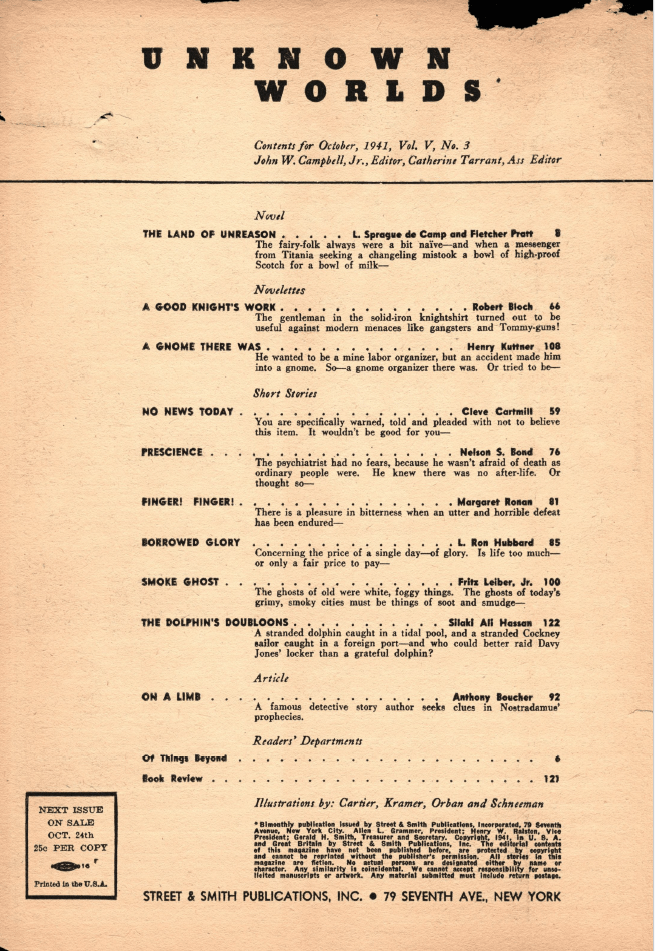

Pretty rad ToC in this issue – the de Camp and Pratt Novel up front is great, one of their “Mathematics of Magic” series that is, I think, criminally underappreciated among fantasy folks. There’s a good Kuttner story in here, a lesser (but still fun) Bloch effort too, as well as some of Hubbard’s usual hackwork. Anyway, a solid issue of the magazine, made more interesting by the editorial (“Of Things Beyond,” on page 6) where Campbell and Tarrant are trying to couch their style of fantasy as something more urbane and, frankly, science fictional than the traditional (i.e., Weird Tales) stuff. It’s always interesting to see the genre discussions going on in the pulps – we tend to take the labels for granted these days, but there was a real tension about what exactly was, say, sci-fi or horror, and the only place to hash them out was in the magazines!

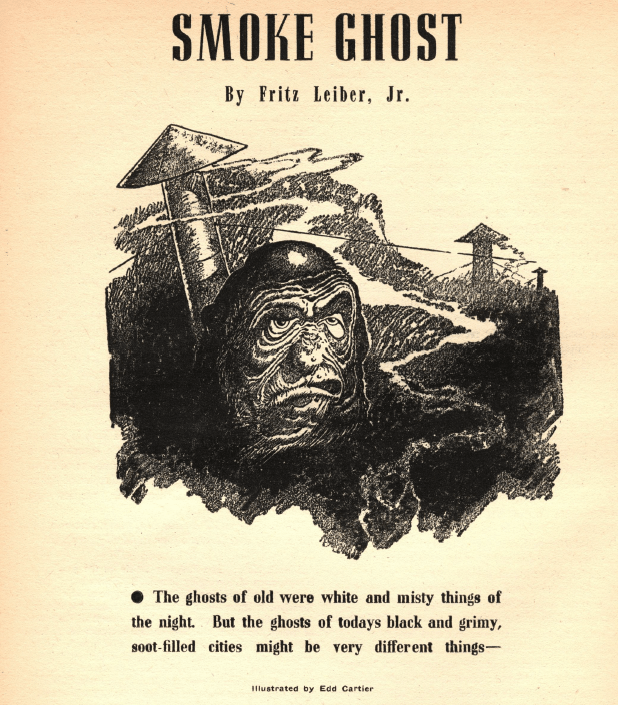

But, anyway, enough! Let’s get down to business with one of my favorite weird stories of all time, “Smoke Ghost” by Fritz Leiber, Jr!

Good, almost “EC Comics” ghastly ghoul there, huh? Cartier is among the top of the heap, especially in the sci-fi magazines, and had a long and storied career as an illustrator, with a fun and playful style that I like. Also really appreciate that this bit o’ art doesn’t give anything away at all, a rarity in the pulps sometimes!

A fantastic opening, isn’t it? A secretary is wondering what the hell is up with her boss, and who can blame her when he’s spouting off truly wild, apocalyptic ideas about the kind of ghosts born into a world of steam and smoke and capitalism. “The kind that would haunt coal yards and slip around at night through deserted office buildings…” I mean, holy smokes, great stuff! And there’s more! Miss Millick is taking dictation from him when he has another odd interlude:

Absolutely killer stuff here, and a good overview of not only the theme of this story but of a lot of Leiber’s fiction, where myths and beliefs and monsters are a dark reflection of the material conditions of life, a kind of instantiation of collective fear and pain whose form and expression comes from the specific types of sordid miseries visited on people. And here, in this story, written at the tale end of the Depression (though who was to know that) and while Europe was engulfed in World War II (with America watching from the sidelines, as yet), Leiber is evoking a particular flavor of modern, industrialized hauntings.

I hope Miss Millick is stealing office supplies, because goddamn that is one grim diatribe to be enduring for thirty-five cents an hour or whatever the going rate for secretarial work was in 1941. She objects that, of course, there’re no such things as ghosts, but this seems to only send Mr. Wran further ’round the bend. With a huge, tight, unnatural smile, he spouts some boilerplate about how of course there’s no such things as ghosts, modern science assures us of this very fact yadda yadda. It’s all very strange for Miss Millick, who nervously runs her hands across the edge of Wran’s desk…and discovered that it’s covered in some kind of weird black smudge or gunk.

Strange how the sight of that dark grime seems to affect him so, huh? When Millick is gone, Wran runs over and examines the black gunk – he’s obviously troubled, because not only does he furiously scrub the stuff off the desk, we also learn that the trash basket is full of similarly inky rags…this weird grimy shit seems to be part of some kind of regularly occurring phenomenon, tied in with other things that Wran, attempted to convince himself, calls “hallucinations.”

And what are the things he’s been “hallucinating?”

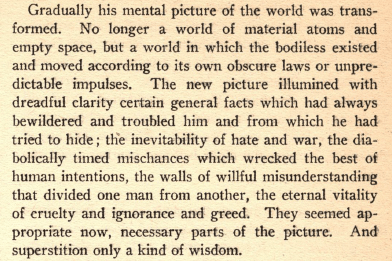

I gotta watch out, Leiber is such a good writer I’m in real danger of just copy-pasting the whole damn story onto here. But I mean, c’mon, how evocative and moody and moving is that passage? This bleak, almost nihilistic scenery is as terrifying and as existentially threatening as any of Lovecraft’s Cyclopean ruins, and the psychogeographical connection between it and the troubled times (specifically the “Fascist wars”) is really phenomenal. Also, neat writerly trick of Leiber’s, tying Wran’s observation of this scenery to dusk and twilight only, doubling down on the sense of fading light and ending cycles.

It’s during these Blakean reveries that Wran captures sight of something – it’s nothing at first, just some windswept garbage…and yet…

That’s a real lived-in moment, isn’t it? One summer, when I was doing field work out in Wyoming, I watched the same same pile of antelope bones slowly disarticulate and scatter down hill. It was on the path I would hike to get to some outcrops, and for like two weeks I saw the steady movement of vertebrae and ribs and long bones, starting up near the ridgeline and, as a result of time and curious coyotes and intermittent rain storms, ending up at the foot of the hill in a little dry creek bed. It’s an interesting thing, getting to “know” a bit of ephemeral stuff in the landscape, and Leiber beautifully describes Wran’s fascination with this weird, oddly behaving bag of trash. And of course, the fun part is that Wran doesn’t know he’s in a weird tale (yet), but we do, so we know that the strange peripatetic movement day by day of this horrible bag thing is much more portentous and threatening than poor ol’ Wran does.

Wran finds himself obsessing over the weird bag thing – when it’s not visible one day, he’s oddly relieved, and then becomes annoyed with himself for, apparently, having been worried about seeing the thing. The next evening, he tries to ignore it, but the desire to look out the train window at the thing’s usual spot proves too strong, and he does indeed see something: it looks like there was a head of some sort, peering over the parapet of the roof.

At this point Wran really is justified in his assumption that he’s developing some kind of psychosis – the things is dominating his thoughts, and he develops a weird compulsion about grime and dust and inky grit that he suddenly is noticing everywhere in the office. Similarly, he decides that this is something he has to confront, and so, one evening on the train, he strains his eyes looking out over the grim cityscape.

And so Wran decides to visit a psychotherapist.

Leiber was, like a lot of people, intensely interested in psychiatry/psychology – we now tend to not really appreciate how HUGE and REVOLUTIONARY the idea that the brain was “fixable” had on people in the early 20th century. In our modern world of commodified and wide-spread therapy, it’s kind of taken for granted, but back then there’s a real sense that not only is it possible to interrogate and adjust the human mind, but it could be done scientifically. There’s a reason why people like Sturgeon, Campbell (the editor of the Unknown Worlds), and Philip K. Dick were such devoted believers in PSI/psychic stuff, and why it shows up so often in the science fiction of the day – it was bleeding edge science, doing for the mind what medicine was doing for the body and what physics and chemistry promised to do for the external world. Leiber, who received undergrad degrees in both psychology and biology, was uniquely equipped to integrate these concerns into his fiction.

Wran’s visit to the head-shrinker allows him to relive and explore the “unfortunate incident” that Miss Millick had alluded to earlier in the story. It turns out that ol’ Wran was, apparently, a psychic kid, although that’s really the least important part of the story – what TRULY matters here is the Wran, while apparently clairvoyant, continuously disappointed his mother because he could NOT communicate with the dead. The fact that this “sensory prodigy” could only see real, physical objects and NOT spiritual ones is interesting, in the context of this story.

Childhood Wran’s life as a psychic oddity is interesting – it seems like he mostly hated it, but he desperately wanted to please his mother and other adults, all of whom paid attention to him because of his gifts. This need to please is so great that it maybe ends up sabotaging him; his first public test at a university elicits such anxiety that he ends up psyching himself out and, apparently, loosing the ability totally.

At this point, we have been told a few things about Wran that’re important to the story – he’s a needy little guy, he had a brush with the occult world as a child that has resulted in him turning away from the unknown and towards placid rationality (see, in particular, all his talk about science and his desire for an expert to tell him everything is okay) and, most interestingly, his psychic power ONLY worked on real, physical objects…he never spoke to the ghost a dead person, no matter how hard his mother pushed him.

All this is very interesting, and Wran is even apparently feeling a little better from having taken the talking cure when, suddenly…

Don’t be bothered by the uncomfortable usage of the age here – it’s unfortunate phraseology, but the needs of the story justify it I think and, besides, trust me; in hands other than Leiber’s it could be waaaaay worse. Anyway, the bag thing has obviously followed Wran to the doctor’s office, which is freaky as fuck. Also interesting is that the doctor sees it too – this isn’t something only the “sensitive” can see, it’s a real physical presence in the world!

Obviously, Wran decides it’s time to wrap it up, and he heads out – he’d been hoping modern psychiatry would be enough to solve his delusion, but now he knows that’s all done with. There was no delusion; the bag thing was real. He wanders around the city, taking comfort in crowds and lights, only to find himself wandering back to his office. He realizes that, subconsciously, he’s recognized that he can’t lead the bag thing back to his home, where his wife and child are. Dejected and without a plan, he heads up to the office, mulling over his newfound enlightenment:

His thoughts are interrupted by a sudden phone call! It’s his wife, with some troubling news!

The bag thing is at his house anyway! He hurries out the office and calls the elevator, looking through the grate and down the shaft…

…where he sees the bag thing…

Wran is looking down the elevator shaft, and the thing is three stories below, looking up the shaft, directly at him. I mean, that is some killer, chilling stuff, isn’t it? Just spectacular, and it’s only going to get better – we’re entering the home stretch of the story, and Leiber is just about ready to let us have it.

Wran flees back into the office, locking the door and retreating to his desk, terrified out of his mind. He hears the elevator come up to his floor, and then a silhouette appears in the glass of the office door. Why, no worries! It’s just Miss Millick!

Yeah…poor ol’ Miss Millick has been possessed. This begins one of the scariest sections in basically all of literature. Leiber has made Millick into this terrifying avatar of something inhuman and alien, and it’s just some spectacular stuff:

The tittering, the weird playfulness, the way it starts every sentence with “Why, Mr. Wran…” and then the horrific alteration of Miss Millick’s body, followed by the implacableness of the thing…it’s absolutely spectacular, and the last line of the section (“I’m coming after you”), I mean, it doesn’t get any better than this. Absolute top notch weird horror.

Wran flees to the roof, but of course the thing follows him.

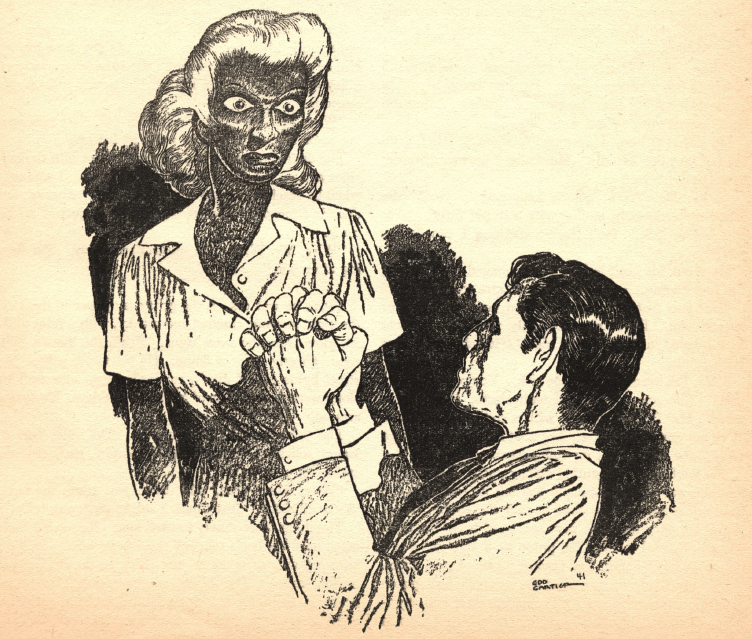

Chilling fucking stuff. There’s even a fun, spooky illustration of Wran’s abjectification:

The thing titters, demanding total abasement from Wran:

The thing, pleased with Wran’s submission, releases its hold on Miss Millick, and Wran is left alone, having pledged himself totally to his new god, The Smoke Ghost. He helps Miss Millick, who for the life of her can’t understand how she ended up on the roof, and then the story closes:

I mean, goddamn, am I right? A hell of a story, and such a rich text, with so much going on. The big picture, at least for me, is Leiber very much recognizing the dark truth of his (and, now, our) times: the age of “rationality” is an illusion. Rather, we live in a haunted world, one stalked by the phantoms of fascism, of capitalism, of industrial gigantism, of smoke and soot and abjection. Wran, confronted by the implicit threat of this world, breaks immediately, begging for his life at the feet of the oppressor and promising to serve and worship it utterly. It’s dark stuff! And kind of a bummer! Sorry!

Setting aside the crushing existentialist horror of the story, though, I think we can all agree that it’s also a homerun in terms of being a technically perfect piece of weird fiction. Not a sour note there, the pacing is great, the build-up is spectacular, the weirdness is solid, and when the horror starts up it gets really good, really fast. It’s also such a great, original take – the Smoke Ghost is a specter of modernity, a being called into existence by a world of rampant, soulless capitalism and wracked by fascist war. There’s even a bit of early environmental critique here – the ghost is a thing of garbage and soot; it’s physical presence is one fundamentally of pollution and corruption.

Obviously, I love this story; it’s definitely one of my favorites, a great example of Leiber’s mastery of weird fiction. A perfect way to celebrate Halloween!