CONTENT WARNING: the story we’re talking about today includes sexual assault.

A hyperborean wind howls from the north, locking my Texan kingdom in the icy grip of mid-40 degree temperatures, which can only mean one thing: Sword & Sorcery month is upon us again!

As I mentioned last year, I have long associated the Yule with fantasy in general and sword & sorcery in particular – something about the atmospherics and the holiday free time lends itself to curling up with some rollicking barbarians-and-wizards action, you know what I mean? Last Sword & Sorcery month, we talked about a lot of fun stories either leading up to the genre – the Solomon Kane story Rattle of Bones for instance, or my favorite S&S tale of all time, Worms of the Earth – or those firmly within its walls, like the classic Conan adventure The Tower of the Elephant, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser’s first story Two Sought Adventure, or Black God’s Kiss, the very first Jirel of Joiry tale.

That last one on the list above is relevant, because it strongly influenced which story I wanted to do today. Again, as is tradition, we gave November over to C.L. Moore stories, and like last year I moved from Moorevember into Sword & Sorcery month with the very first Jirel story. So, with frightful symmetry, let’s start of our celebration of all things sword-and-sorcerous with the LAST Jirel story that C.L. Moore ever wrote, the absolutely killer Hellsgarde!

As is clear if you’ve been reading these long rambles of mine, Moore is one of my favorite writers, and Jirel is one of my favorite characters – she’s really a singular creation, a badass swordswoman in full command of herself and her destiny; she’s not some wandering mercenary or exotic barbarian, she’s a goddamn robber baron(ess), ruling a castle and with a band of rough-and-ready slayers under her command. Interestingly, it’s that singular independence that serves as the instigating factor for most of her adventures – in the first story, we meet Jirel after her defeat, with her castle occupied and herself a prisoner. The threat to her autonomy that this represents leads her to take a drastic and blasphemous path towards vengeance, with a grim and tragic result. Jirel’s saga is bookended by a similar constraint in “Hellsgarde;” here, Jirel has been forced into dire action by the treachery of a (strangely attractive) man, and she also ends up facing strange, alien, and altogether blasphemous magic, a source of pervasive corruption that, I think, really sets the tone for a lot of sword & sorcery later.

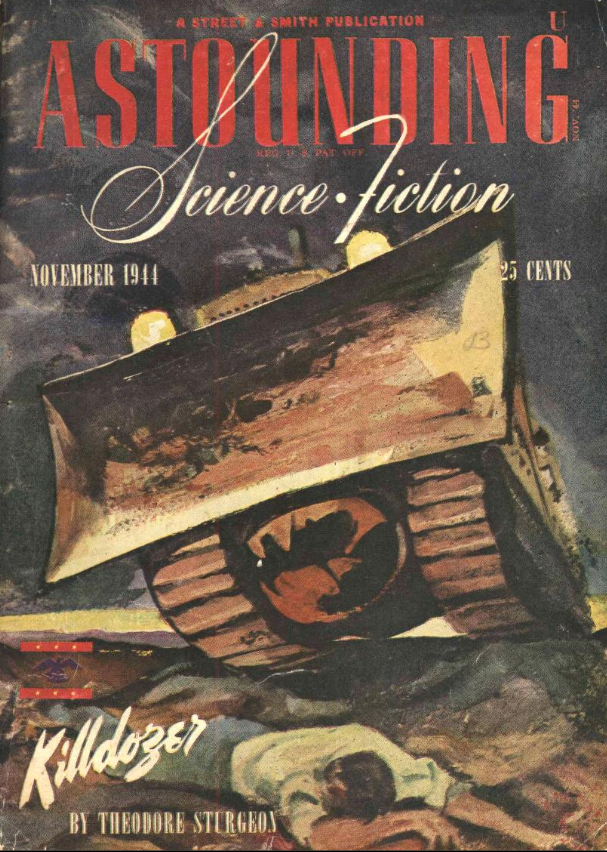

But, before we dive into the story, let’s look over this issue of Weird Tales!

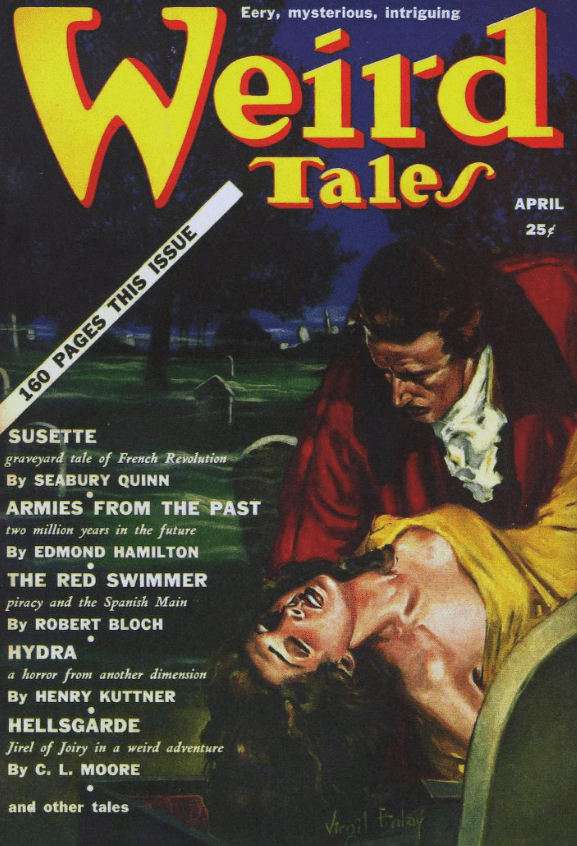

The cover, by Virgil Finlay, is a little disappointing and bland, a shame given what we know Finlay is capable of. In fact, there’s actually some killer Finlay art in the magazine, so let’s take a minute to wash the dullness of the cover out of our eyes with some of that, shall we?

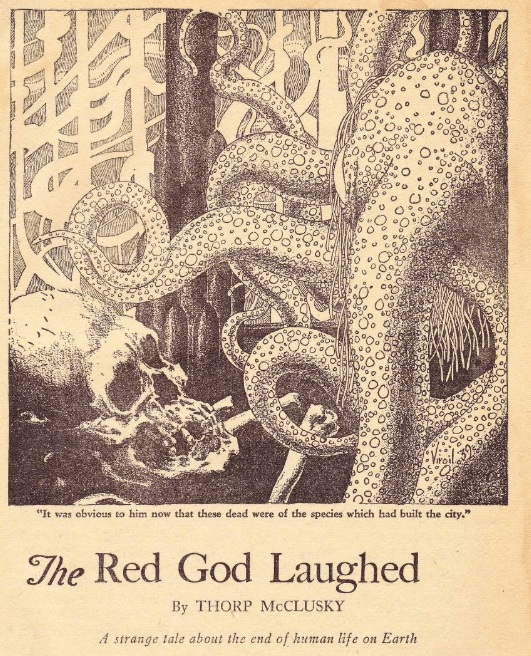

I mean, holy smokes, lookit that! Great, weird art for McClusky’s (middling) story “The Red God Laughed. And lookit this:

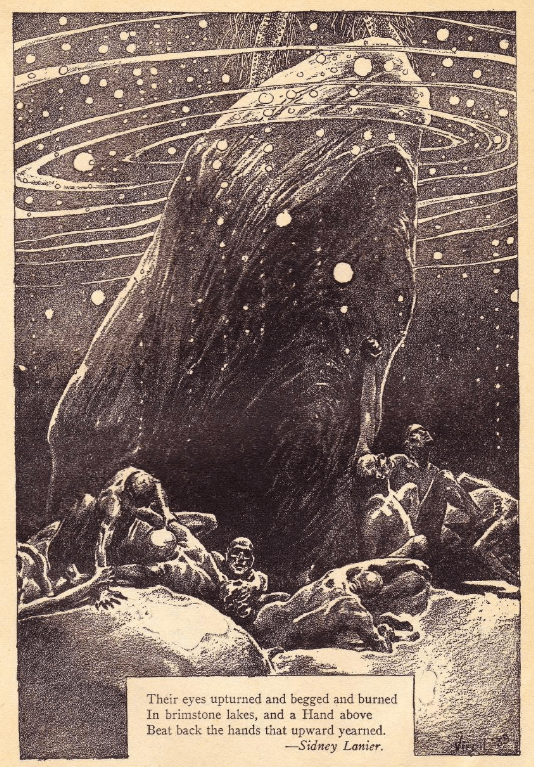

Late Wright-era Weird Tales would do these one page spreads where an artist would take inspiration from a short passage, often of poetry, to create these marvelous full illustrations. I mean, jumpin’ cats, what a piece, huh? Baffling that Finlay’s cover is so dull when he’s capable of masterpieces like this, isn’t it? But oh well!

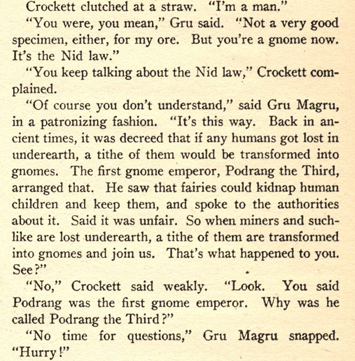

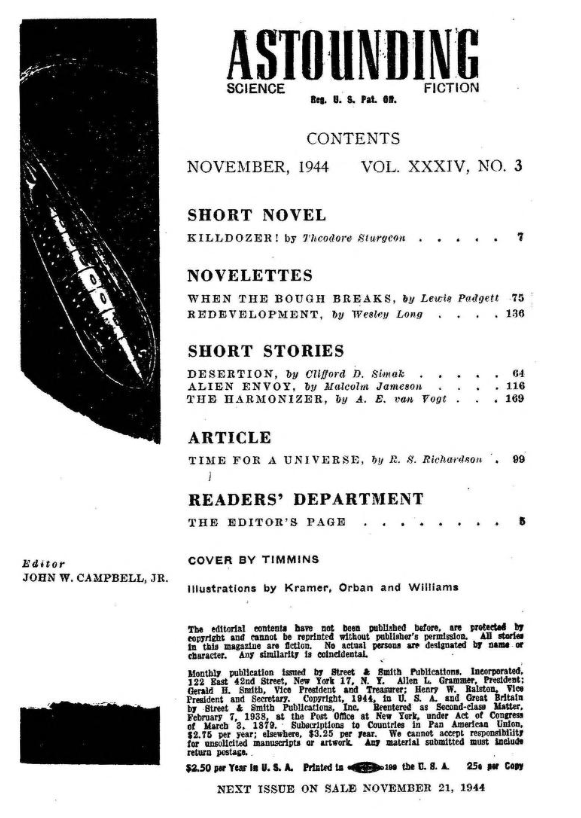

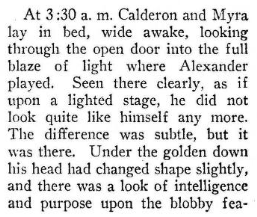

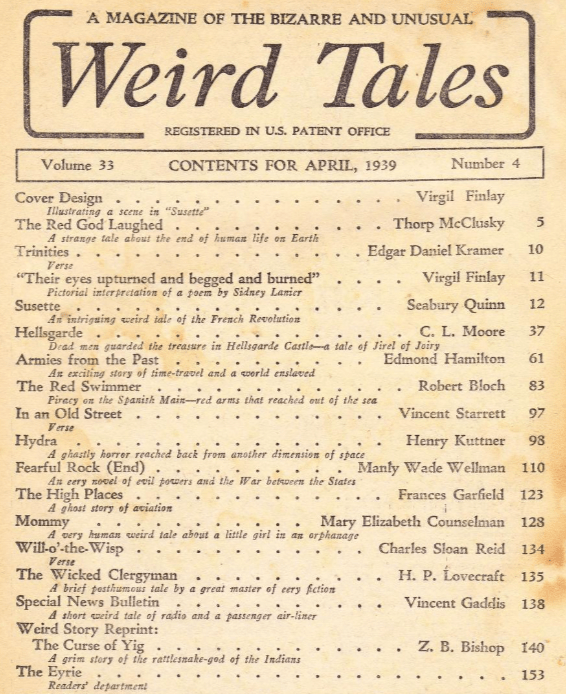

The ToC is interesting:

At first blush, there’s not a lot to recommend this big ol’ issue, is there? A lot of second-stringers, in my opinion; Moore’s Jirel story is the stand-out, from our perspective today at least. Folks back then loved Quinn though, which is probably why his (perfectly fine but nothin-to-write-home-about) story got the cover. Bloch is still working to find his niche – there’s a bit of gratuitous violence and gore in this one, hints of things to come for ol’ Bob Bloch. Moore’s husband and writing partner, Henry Kuttner, has a story in here, and it’s 100% a Lovecraft story, with two weirdos doin’ occult experiments to contact things from Beyond and all that. There’s some funny drug stuff here too, with the occultists using weed as part of their mystic preparations. It’s actually not a bad piece of Lovecraft inspired fiction, even if it does come off a bit derivative and pat. He even excerpts the same passage from Machen that H.P. used in “The Horror at Red Hook!”

But speaking of the Old Gent, there’s two Lovecraft pieces in this issue, pretty good for a guy who’d been dead for two years. “The Wicked Clergyman” is unusual, in that it’s an excerpt of a letter that Lovecraft sent to a friend, Bernard Dwyer, in 1933, and the part that became this story is basically him recounting a weird dream he’d had. Following Lovecraft’s death, Wright took some effort to gather up any remaining bits an pieces of his work and publish (or republish, in the case of the amateur press stuff) things like this in the magazine. On the one hand, it’s nice this stuff got preserved, but on the other, you can’t help but feel like a note about this story would’ve been nice, at least for Lovecraft’s sake – this isn’t a “story” per say, and not knowing its provenance might give a reader a weird idea about Lovecraft’s work and style.

The other Lovecraft piece is a reprint of Zelia Bishop’s 1929 story “The Curse of Yig.” Bishop is a very interesting character who hired (and occasionally actually paid) Lovecraft to do some revisionary/ghost writing work, which she then sold (or offered) under her name. By far theirs in the most “impactful” collaborations in the mythos world; these stories introduce Yig the Father of Serpents into the pantheon. They’re also interesting stories for their western flavor – they’re set in Oklahoma and have a decided “frontier” aspect.

A long ramble, but the point is that Moore’s “Hellsgarde” is coming in at a strange and chaning time for the pulp world – the old masters of Weird Fiction are, for the most part, dead or in decline, and the powerful editor of the magazine, Farnsworth Wright, would soon follow them. Simultaneously there’s more competition, particularly in the sci-fi (and fantasy) realm out there, magazines that had bigger budgets and could pay better prices than The Unique Magazine. Every Jirel story that Moore wrote appeared in Weird Tales, but the landscape of magazine publishing was changing, and Moore (and Kuttner) would expand their markets, particularly as sci-fi grew in popularity.

But, anyway, enough! Let’s get to “Hellsgarde” already, yeesh!

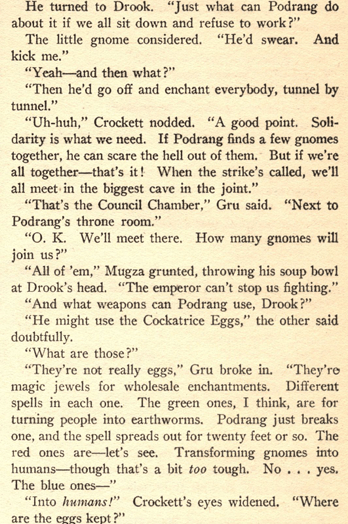

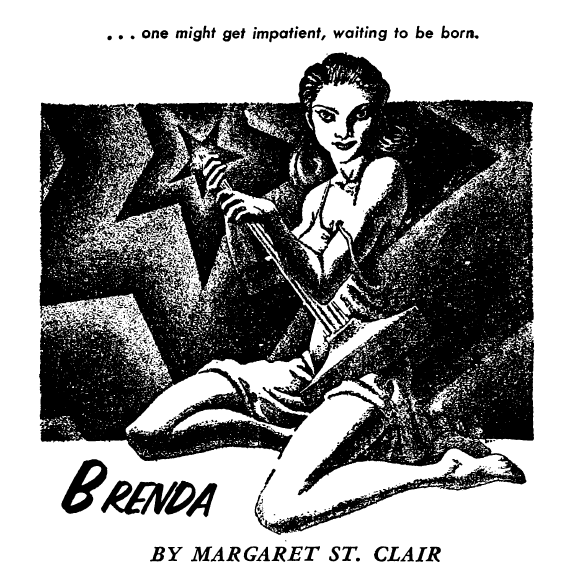

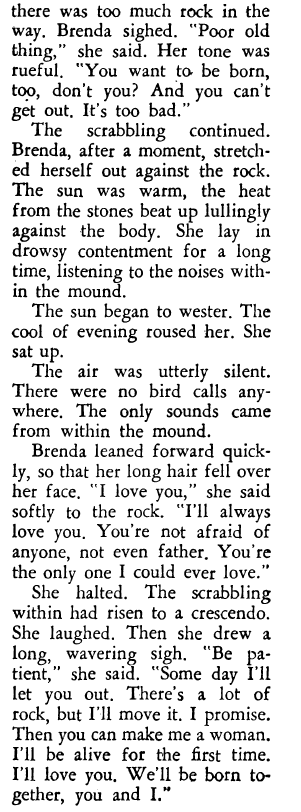

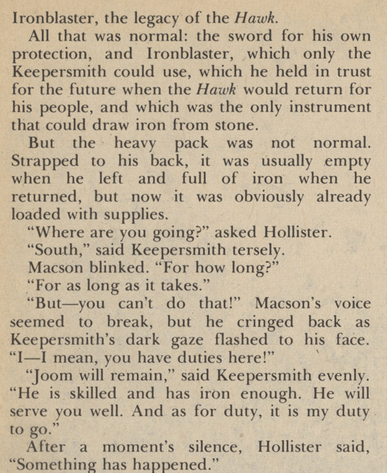

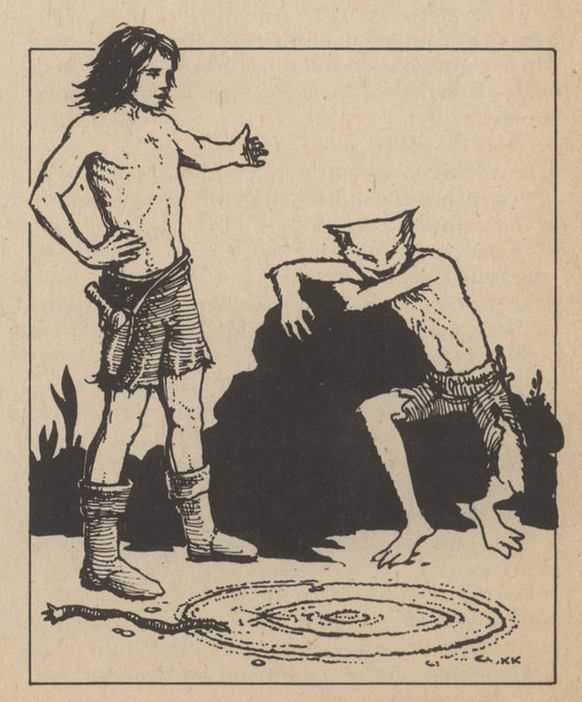

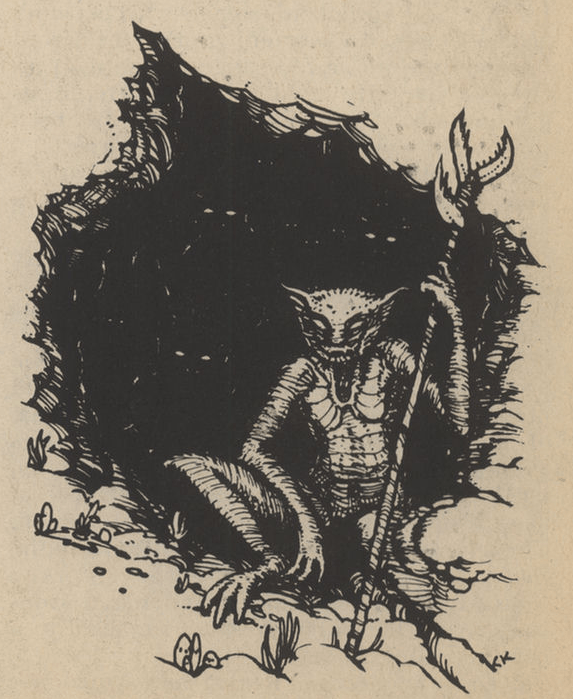

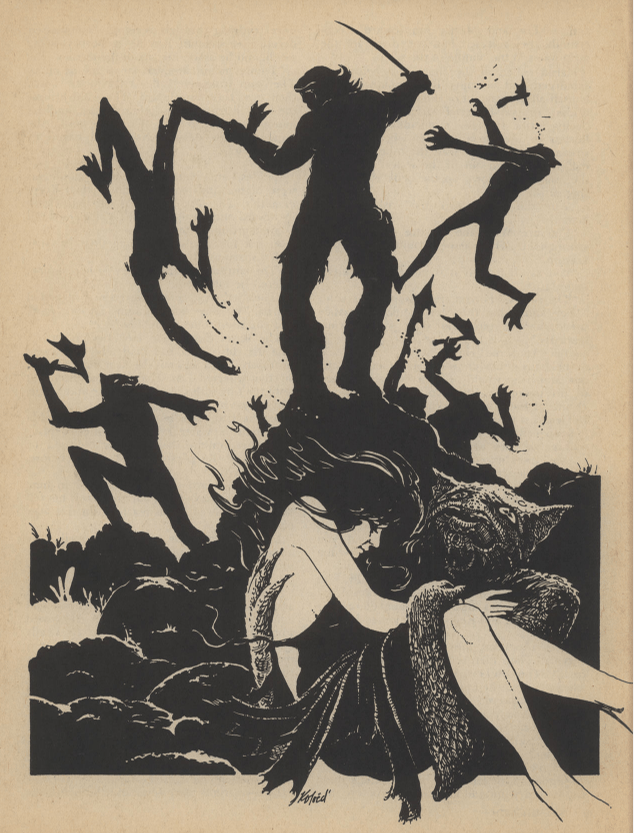

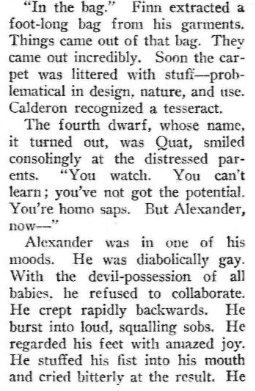

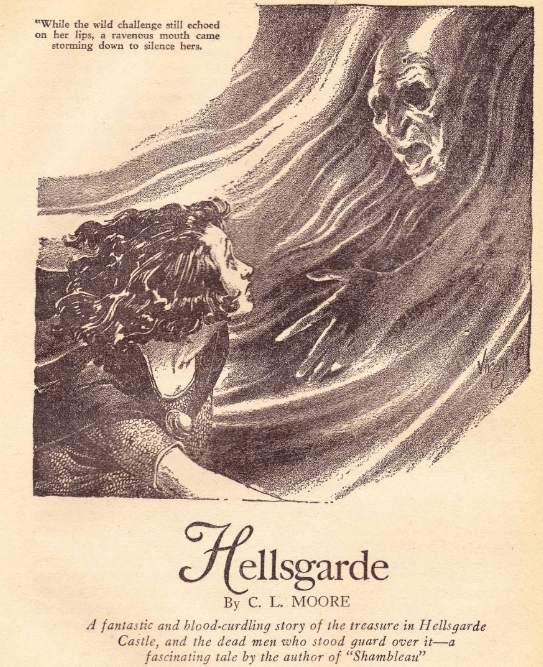

Good illo by Finlay, of course, although I can’t help but wish he’d taken on the weird “nobles” that Jirel meets in Hellsgarde, with their subtle but definite “wrongness.” Oh well! Also interesting how Moore is still being connected with “Shambleau” all these years later! It’s an important story, and it definitely had a very strong impact on ol’ Farnsworth and the Weird Tales world!

We open the story with Jirel, mounted upon her mighty steed, staring out over a strange and empty swampland just as the sun is setting. There’s some great environmental writing here – I think sword & sorcery is a genre uniquely suited to this sort of thing, landscapes and “wilderness” I mean, given the deep resonance they have with themes of natural vs unnatural, civilization vs barbarism, and the contrast between the smallness of the protagonist and the hugeness of the forces arrayed against them. Moore, who is simply a great writer, does this stuff really well too – the glassy unnatural stillness of the swamp, the silence, the long dying sunlight, it’s fantastic stuff, top-notch writing.

And why has Jirel come to this ruined castle of Hellsgarde in the lonely vastness of this swamp? Why, ’cause of a dude, of course:

So first off, there’s more of that strange sexual tension that Moore is so interested in. Jirel is, once again, obviously experiencing some complicated emotions – Guy of Garlot is a scumbag and a villain, but he’s easy on the eyes, that’s for sure! It’s an interesting bit of characterization for Jirel too, since she’s obviously at least appreciative of his physical attractiveness, even if he’s “ugly as sin itself” on the inside. But how’d this hot asshole get Jirel to agree to go questing for Hellgarde Keep in a haunted swamp?

Guy has, somehow, captured 20 of her best bullyboys, and unless Jirel, fearless and mighty swordswoman that she is, retrieves the treasure of the Lord of Hellsgarde, then they die! Guy apparently desires Andred’s treasure above all things (scorning even Jirel’s rockin’ bod!), and will only exchange her men for it; but it’s a deadly dangerous quest, for all who have gone into the ruins has vanished. And what is this treasure? Hilariously, Guy doesn’t know – it’s something small and said to be stored in a box, that’s it. I guess he’s just jazzed about it because it’s so rare a prize and no one has been able to get it? Jirel, pissed off, is forced to agree the bargain; after all, regarding her men:

Great bit of characterization there, huh? Jirel understands honor and the obligations she has to her soldiers – if she must, she’ll go into this preternatural swamp with its haunted ruin and search for a cursed, mysterious treasure, all for the sake of her twenty dudes.

Jirel rides down towards the castle, and we get some more great descriptive writing:

What a vision, huh? As she goes, she has an expository reverie that lets us learn, quickly, a little bit about Andred. A big, violent, mean fucker in life, the rumor of his weird little treasure box was enough to draw his enemies to his lonely castle, where they besieged and captured it. His treasure hidden, Andred was subjected to the most terrible of tortures, but his raw vitality and stubborn strength meant that, after long sufferings, he died and took its secret with him. No one found the treasure, and eventually the castle was abandoned…

Standard issue vengeful ghost guarding its treasure, although take note of the fact that Andred’s ghost is said to be a direct result of the vitality and force that he had in life.

The mists continue to rise around Jirel as she rides towards the castle along the causeway, and she thinks they must be playing tricks on her eyes, because it almost looks like there’s some guys stationed in front of the gate of this abandoned castle. That can’t be though…can it?

It is a bunch of guys…dead guys! All stuck by their own spears! It’s a gruesome as hell scene, and very uncanny. Jirel, of course, is no stranger to death and brutality; hell, honestly its easy enough to envision her ordering the same thing done to some guys she’d killed…but out here, in the swamps, something is making sport of death, and it’s damn spooky! While she’s regarding these dead men, the door to the castle suddenly groans open…and a weird little guy greets her.

Now, first thing to point out and mull over is the somewhat uncomfortable way Jirel articulates the wrongness of this fellow. He’s described in frankly ableist terms, something that we find a little offputting these days – the idea of a villain’s disability being used in some literary way to reflect their twisted soul is not only offensive, it’s cliche, a very common trope from the past. Now, within the context of this story, I think you can approach it as the way Jirel, an indeterminately medieval person, would view the world around her. I mean, within the context of stories and literature from the broadly defined medieval Europe, that was a common and self-evident view, moral decay or sin stamped on the body or face. In detail, it’s important to recognize that Jirel is perceiving a kind of moral deformity in this guy – he’s not actually a hunchback, after all, and the clumsy and uncomfortably language we can choose to read as diegetic here, Jirel articulating a strange new concept to herself. It’s also of a piece with her reflections on Guy from earlier in the story – she several times brought up the apparent contrast between him being grade-A beefcake and a vile asshole. This discourse on form and (evil) function is an interesting one here, a key theme of the story.

This weird creep says he works for the lord of Hellsgarde, a guy by the name of Alaric, who holds court here. That’s news to Jirel – as far as she knew, this pile was a ruin and no one lived here. Alaric, however, appears to claim some distant ancestry with Andred, and as such has taken the castle as his inheritance. Jirel is troubled by this – doubtless anybody living in Hellsgarde would have searched it thoroughly for the treasure. Has this Alaric found it? And even if he hadn’t, as a descendant of Andred, he would, ostensibly, have more of a claim on the treasure than anyone else. Either way, her plan is somewhat complicated by this development. And so, Jirel tries subterfuge. She’s just travelling through the swamp, will this fellow’s master give her shelter for the evening?

Inside the courtyard of the castle, Jirel sees a gaggle of extremely rough dudes. They’re obviously evil thugs, but at least their particular evil is something human and understandable to Jirel, in contrast to the majordomo and, as we’ll soon see, Alaric and his household.

Horse stowed, Jirel is led into the main hall where, at the far end, there’s a huge fire in the hearth and a semi-circle of people around it. Immediately though, Jirel catches a hint of “wrongness” about the scene. The fire seems merry enough, but there’s something about the people sitting around it, their faces and postures, that seems odd and strange. A man, obviously Alaric, sits in a highbacked chair, and a strange lute player (someone actually with a hump, it turns out) seems to be looming over the back of the chair. On cushions or benches there’s a “handful” of women and girls, as well as two small preternatural boys as well as a pair of scarlet-eyed greyhounds. All eyes are on her as she strides across the hall towards them, and knowing this, Jirel struts as she approaches them:

Again, Jirel is such a fun character. She’s a badass warrior AND a stone-cold fox, and she not only knows it, she revels in it! Honestly, a lot of warrior women in fantasy stuff aren’t allowed to have this much fun – they’re either weirdly (and coquettishly) virginal or absolutely sexless. But Jirel, in addition to obviously being someone who fucks, is allowed to have fun with it too; her sexuality is another weapon in her formidable arsenal, one that she deploys against men and women alike (I don’t think we’re meant to take that last little aside in the paragraph above as sapphic in any way, though – I mean she’s perfectly willing to let those 5s know that she’s a 10.) (Although you can put whatever the hell you want into your fanfiction, of course.)

Up close, the weirdness of these people is even more evident – there’s the same kind of spiritual deformity that she recognized in the doorman in Alaric and his jester, a hint of something twisted and off behind their eyes. And the rest of the household is no less strange. The women are strange beings, tall and with shockingly large and staring eyes, a similar shadow of evil hanging on them. The dogs are hellish things with red eyes and a foul disposition, and the two young boys, while silent and watchful, have the faces of devils with cruel, lusterless eyes. Equally weird is that it’s never made very clear how all these people are related to one another, despite the clear affinity for evil shared between them.

Despite the weirdness and menace of these oddballs, Jirel has a mission to do. She asks to stay the night, and Alaric graciously offers her room and board. She settles in among the throng, although she keeps her sword handy and her reflexes primed – she does not like these people and senses something is wrong and very dangerous here. She and Alaric fence verbally, although every time she asks a question about them or their experience at Hellsgarde, a ripple of subtle amusement runs through the whole company, as if they’re all sharing a secret joke. The whole scene is great and very weird; Alaric et al are just flat out odd; they’re clearly watching her hungrily the whole time, but we’re right there with Jirel in not understanding what it is that they’re after. She (and us, the readers) have to be thinking that this, in some way, orbits the question of the treasure; perhaps Alaric has guessed her errand, and is laying a trap for Jirel? Who knows! But then, supper is served, and Jirel’s brief relief at the normalcy of a meal is soon replaced by further unease:

But, when the table is set and the meal begins, it turns out everything is a little…off:

Brave woman to bite into whatever unrecognizable beast had been roasted. But then again, everything tastes bad and foul and rotten. Jirel is the only one who seems troubled, though – everyone else is digging in with gusto. And then Alaric notices Jirel isn’t eating:

Grade A weirdness! I love it! It’s particularly fun to take this hyper-competent character, a cunning and clever warrior, and put her in a situation where that really doesn’t matter, where something totally alien and strange is happening, and she’s just kinda gotta ride it out. And the menace behind these weirdos is good and palpable too – this strange group with their furtive jokes and their staring eyes and their evil auras. Solid stuff!

Following the bad meal, Alaric offers to show Jirel the great hall full of armor and banners and whatnot. It’s all rotted and rusted of course, what with being an abandoned castle in the swamp and all, but while they’re promenading Alaric escorts her to a huge stained patch of stone floor – the very spot where Andred died, dismembered and broken by the long tortures he’d endured. And, while Jirel is regarding the spot:

A sudden furious storm seems to descend on her, right there in the hall. The lights go out, she’s seized in an oddly disembodied grip, and a mouth is suddenly thrust upon hers, bestowing a “savagely violent, wetly intimate kiss” unlike anything she’s ever experienced (gross!). At the same time, she’s being bodily dragged across the hall by some kind of implacable, unstoppable force. It’s very weird! And maybe very uncomfortable for the reader, since Moore makes sure that we know that Jirel is 100% experiencing this kiss as a violation. Her mouth is “ravaged,” she’s gripped by an “insolent” hand, she can only make inarticulate sounds since her mouth is sealed by the “storming violation” of the kiss; it’s very much a sexual assault, and the suddenness and overwhelmingness of it is very shocking to the reader.

Anyway, as this is happening, Jirel is also experiencing a sense of claustrophobic confinement, as if she’s being dragged out of the hall and into a small room or closet. It’s pretty frightening, obviously, but just as suddenly as it appeared it vanishes. Suddenly there’s light in the hall again; one of the weird women has tossed a bunch of brush onto the doused fire and suddenly there’s a blaze going. Jirel sees that she’s standing alone in the far end of the hall – the rest of the people are by the fireplace, and Alaric himself is standing over the stain, at the other end of the hallway. She has been dragged across the room, although she was never “confined,” and it’s clear that Alaric, who had been near her at the beginning of the attack, had not been the person to grab and assault her.

It suddenly becomes clear that Alaric and the others had expected something like this to happen. They’re speaking in a weird language Jirel doesn’t understand, but they’re all very excited and running around with a strange, hungry look in all their eyes. Alaric questions her about what happened, and they all get very excited when she muses about it being the ghost of Andred.

We learn that Alaric and his weird crew have been waiting here for the ghost of Andred to appear, but it hadn’t come out until Jirel shows up – Alaric speculates that Jirel has a kindred fierceness that Andred’s spirit finds irresistible. Similarly, they, being Andred’s descendants, have not been able to get him to appear (an obvious lie, as we’ll see soon). When Jirel asks why they want to see this horrible ghost, Alaric stammers a bit before saying that, why, only with the help of this ghost can his treasure be found (another obvious lie, and one Jirel catches right away). Anyway, now that Jirel is here, they can get on with it. If she’d be so good as to go stand in the spot again…?

Jirel, of course, tells him to go fuck himself, but then suddenly she’d gripped from behind. No ghost this time, it’s the damn lute player, whose snuck up and pinned her arms. She struggles, but there’s a bunch of them and they quickly grab hold of her. Her sword is taken away, and she’s dragged over the blood stain again. Then, the fire is doused, the hall plunged into perfect darkness, and the people holding her melt away to the far corners of the room. Spookily, it becomes clear that, even though it’s pitch black in the hall, Alaric and pals can see her just fine – they react to her moving around, and even carefully and precisely deliver a pillow to her when she complains of how sitting on the cold floor for hours is uncomfortable.

They wait there in the dark for a long time, until sometime after midnight when it becomes clear that no second appearance of Andred’s ghost is forthcoming. With everything perfectly dark still, Alaric and company grab her up and, without striking a light, carry her off into the castle somewhere, tossing her into a small, locked room. It’s clear that they’re going to keep her imprisoned to try again later.

Then, through the cracks in the door of her cell, she sees a light, and realizes that they’ve summoned one of the human thugs from the courtyard, who has brought a lantern. She waits awhile until, eventually, the guard leans his bulk against the door to take a nap, and she shivs him through the door with the dagger in her greaves. She grabs the lantern and considers her options; there’s a fun bit of meta-fictive playfulness from Moore:

Jirel needs the treasure, and however unpleasant it was, she knows she needs to brave the horrible ghost of Andred again if she wants to get that treasure! So, she sneaks down into the hall, finds the weird stain and, steeling herself, she blows out the lantern.

The challenge apparently works, because she’s suddenly in the center of the supernatural vortex again! She’s grabbed and dragged again across the hall, and all the time the horrible ghostly mouth pressed against hers. And then things get real weird!

Jirel again experiences the sensation of walls closing in, as if she’s being confined in a small room. As this sensation builds, so to does the fury of the vortex, as if they storm is also confined, and therefore all the more terrible. In her struggles, she reaches out and feels cold, slimy, stone walls – she is in fact in a small chamber, one full of bones, the remains of previous treasure hunters! Somehow, this ghostly vortex is magically dragging her into a different space, a pocket dimension or whatever. As she struggles, she is aware of flickering back and forth between the extradimensional prison and the great hall – it’s as if her soul is in one and her body in another. In the prison, she stumbles and picks up the box, and then she fights against the vortex and is back in the hall and her own body, still holding the box – she’s somehow carried it from one space to another. But she’s weakening, the terrible tireless force of Andred’s ghost is beating her down; she knows she will soon be dragged back to the little dimensional prison place, where her bones will mingle with those of the thieves who came before her. As she begins to lose consciousness, she hears a dog barking…and then lute music!

The vortex is still raging, but it seems to have forgotten her, spinning angrily around the hall. But it seems to have been trapped, as spinning around it in a wild Bacchic dance is Alaric and the others, wild and weird and very sinister.

Extremely weird! And what a great bit of writing too, the sense of motion and the wild frenzy of Alaric and the others, and the way that they, suddenly, are much more menacing and dangerous and deadly than Andred’s ghost! Fantastic weird fiction!

Jirel grips the small box to her chest, but she realizes that Alaric and his coven have no interest in it or her – they’re focused solely on Andred’s ghost. The music and the dance wind down, and with it the fury of Andred’s ghost ebbs too. Something is happening, clearly, but Jirel doesn’t see the end, as she finally just konks out.

She wakes to daylight streaming into the hall. She’s sore from all the buffeting that she took, but she’s alive, and she has the small, worm-eaten casket that she grabbed out of Andred’s ghostly oubliette. She looks around, and sees the whole of Alaric’s coven sprawled out across the hall.

A special kind of grimness to the morning-after, isn’t there? And the obscene satiety on all their faces is just a cherry on the top of all this weirdness, isn’t it? There’s a real sense of disgusting, licentious, gluttonous, excess in the aftermath of whatever the fuck happened last night, made worse by the fact that we (and Jirel) don’t really understand anything about what’s been going on! Great weird fiction! And it gets better when she runs into Alaric, the first of his group to come out of their stupor.

I mean c’mon, that’s just fun, isn’t it? You can imagine Alaric, bleary-eyed, needs a shower and a cup of coffee, all cotton-mouthed and stale from last night’s debauch, suddenly being reminded that, oh yeah, that’s right, Jirel is still here. “No worries, I’ll have your horse brought around. Take it easy, bye!” And then of course the capper is that he doesn’t give a shit about the box, help yourself lady! It’s so much fun, and like all great weird fiction, it hinges on us getting a glimpse of something with its own rules and purpose and meaning that we can never really understand.

But of course Jirel demands SOME kind of answer. Alaric explains that they used the lure of the treasure to get her to play the part of the bait for the ghost, since they couldn’t explain what they REALLY wanted from Andred’ shade. Her getting the treasure was incidental to their purpose, as was her survival – she just got lucky that one of the weird dogs had heard her and roused the rest when she was down in the hall on her own. Alaric and the others had swooped in at the last minute almost accidently!

Truly wild stuff, huh? Alaric and his coven (dogs, little boys, and all!) go around eating ghosts, basically – something sweet about the furious dark energies created by their violent deaths. But it’s tricky; he admits that Andred was, rightly, afraid of them, and without Jirel’s own energy to draw him out they might never have had a chance to slurp him up. As thanks, Alaric offers Jirel a bit of advice:

As Jirel rides off, trying to put the memories of the night and the weird horror of the Hunters of Undeath behind her, Jirel regards the box, and considers Alaric’s warning.

And that’s the end of “Hellsgarde,” and the final entry in the original run of C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry stories!

First off, right away, I think it’s great. Jirel is such a wonderful character, her attitude and sharpness and command are fantastic and always a lot of fun to encounter. As weird fiction (the genre that birthed and nurtured sword & sorcery), I think it is again another example of Moore’s command of weirdness and the uncanny; much like the strange hell world that Jirel journeys to in “Black God’s Kiss”, there’s a real undercurrent of alien-ness to everything here. Hellsgarde and its swamp are spooky, but the discover of it being inhabited, and particularly by the strange critters that Alaric and his coven seem to be, just elevates everything. I mean, these hunters of undeath are very strange – are they humans who’ve been changed by their weird appetites, or are they something else? The dogs seem to suggest that there’s something horrible and corrupting about ghost-munchin’ but it’s never explained (thankfully), so you can just kind of savor the weirdness of it all. Great stuff!

As a sword & sorcery story, it’s great, although I can appreciate that some might find Jirel here a little disappointing – she’s often just along for the ride for much of the story, although the fierce joy she feels when she considers her hidden dagger, and the iron determination she expresses by sneaking down to the hall when she’s escaped the prison is absolute top tier s&s heroics, in my opinion. Also, I feel like the threat here is so otherworldly that anything more would break the spell of the story, you know? The ghost is already very scary and strange and obviously something that a strong sword arm isn’t going to be much use against, let alone the weird threat posed by undeath hunters (whatever they are). It would be very dissatisfying if Jirel had been able to, conan-like, brute force her way out of these situations. Much more satisfying is the weird glimpse into an alien world that she got, in my humblest of opinions. Also, she’s got her own agenda here – she needs the treasure to get her guys out of a dungeon, and she’s focused on that above all else, very much in keeping with a s&s protag’s pragmatism!

Of course, we do have to talk about the sexual assault aspect of these stories, particularly since they’re not one-offs by any stretch. I mean, three of the five (ish, I’m not counting “Quest of the Starstone”) Jirel stories are directly about Jirel being violated or threatened with violation. In particular, there’s a strange symmetry between the first story, “Black God’s Kiss,” and this one, isn’t there? The central image of the kiss as violation, for one thing; Guillaume forcibly kisses Jirel when she’s his prisoner, and the outrage of it spurs her on to seek the deadly kiss of the black god to get her revenge. Here, Andred’s kiss is somewhat more straightforward, a violent and unwanted kiss for sure, but one from a ghost many hundreds of years dead; it’s even kind of implied that Andred’s atavistic tendencies are a result of his ghostliness – he’s a thing of violence, almost elemental in death now.

Some people make the argument that Moore, bowing to the realities of pulp publishing, uses “kiss” euphemistically for out-and-out rape in these stories. I mean, I don’t think we’re meant to read these stories, see the word “kiss,” and immediately think that Moore is eliding or winking at what *really* happened. I also think it kinda sorta doesn’t matter, in terms of the story – Jirel experiences these kisses as violations, after all, and that’s enough, although I will say that Moore dwells on the ghostly kiss and its violence a LOT in this story, to an uncomfortable degree. It makes for an odd reading experience, although at least in “Hellgarde” we’re not confronted with as complex an ending – again, the ghost is elemental in its violence, and Jirel can’t have a relationship to it beyond being subjected to it’s innate and impersonal violence.

But, like in so much of Moore’s fiction, there’s a definite fascination with sex and relationships, and an appreciation that there’s positive and negative aspects to all of it. Jirel’s obvious fascination with Guy in this story does make me think of Guillaume in “Black God’s Kiss.” The ending of “Hellsgarde” is also kind of funny, again in a symmetrical way, when compared to “Black God’s Kiss.” Jirel, having slain Guillaume with the horrible and obviously evil magic of the Black God’s Kiss, feels remorse (both for the act, which is tainted by alien forces, as well as because she realizes she had kind of loved Guillaume). But if she learned a lesson from that, she’s obviously forgotten it here! Again she has an obviously evil magic weapon, and sure as hell she’s gonna use it to horribly kill another hot (and evil) guy she has a complex relationship with! It’s pretty interesting that, again, Moore is drawing from that same well for another Jirel story, isn’t it?

It speaks to the strength of Moore’s writing that the stories engender so much discussion; really, there’s no one writing at that time who does so much in such little space. All of her stories are these subtle, complex things, not necessarily puzzles to be solved so much as koans to be appreciated, I think. And they’re sophisticated, to; she’s always diving into heady territory, and using the conventions of the genre (even ones as young as S&S and weird fiction) to really explore and highlight conversations that you otherwise couldn’t have really had (in “straight” lit fic, I mean). Howard (and Smith) clearly influenced Moore’s approach to what would later be called sword & sorcery, but she did something really magical with it, I think, recognizing in it a way to talk about people, environments, relationships, all in new and interesting ways.

Anyway, it’s a great story, Moore is a great writer, and it’s a great way to start of Sword and Sorcery month, I think!