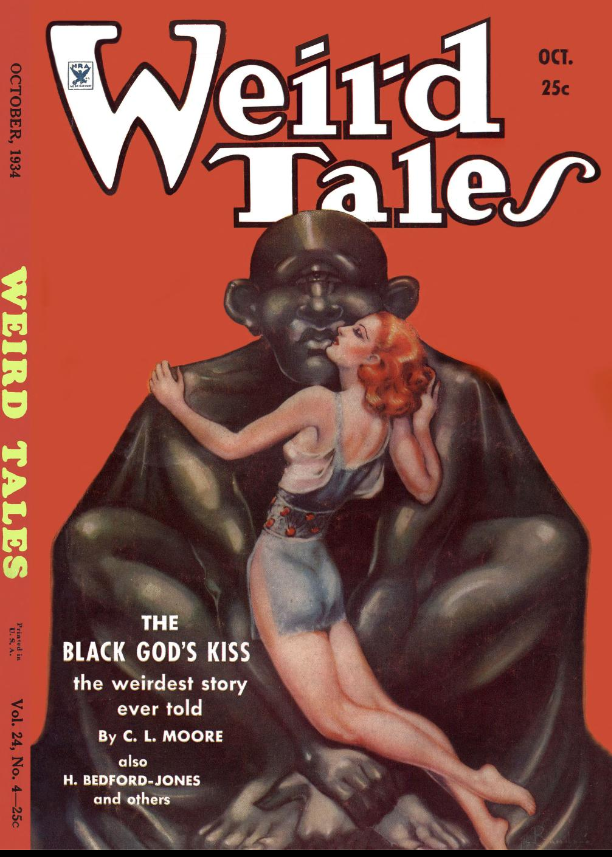

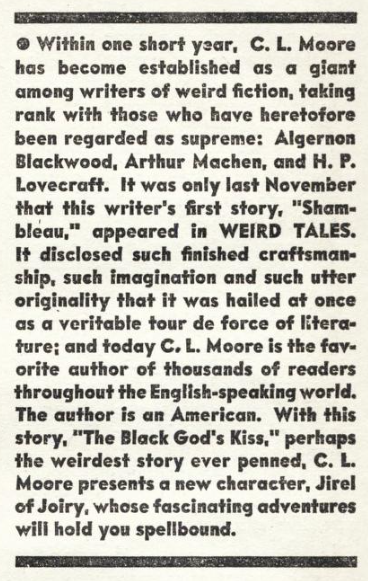

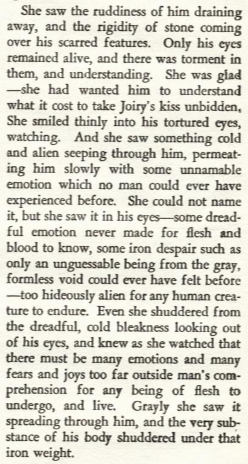

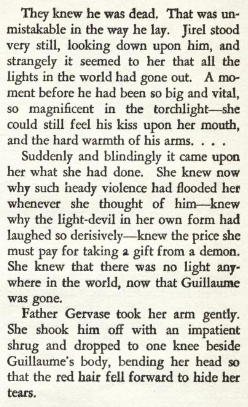

Many names of Great Renown grace the Annals of the Heroic Age of the Pulps, but even in that ancient age of mighty deeds, three names tower above all others with regard to sword and sorcery. Howard we have touched upon twice (and we’ll revisit him soon enough), and we devoted a whole month to the incomparable C.L. Moore, so I reckon it’s high time we hit the final member of the classical sword and sorcery trinity! That’s right, we’re finally going to encounter Fritz Leiber’s foundational duo, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser in their very first published story, “Two Sought Adventure,” from the August 1939 issue of Unknown!

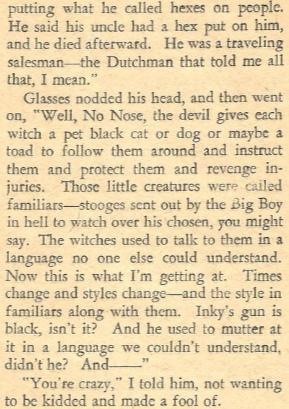

Of course, we’ve already talked about ol’ Fritz, but that was in regards to his weird fiction story “The Automatic Pistol” from 1940 in Weird Tales, which is good and a lot of fun, you should read it. But undoubtedly Fritz’s greatest creations and most lasting renown come from the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories. Given that, AND the fact that he’s the one who actually coined “Sword and Sorcery” for this the best of all genres, I think it’s appropriate to give him another fanfare and more detailed biographical info this time around.

Leiber is, for my money, one of the best writers of genre fiction from the 40s through the 60s, in many ways a predecessor to the New Wave that would revolutionize science fiction in the 70s. His background and various experiences give his writing a depth and vitality that’s really unparalleled, especially for the time; he was the son of Shakespearean actors (and he himself acted on the stage), he was a fencer and an expert chess player, studied for (but did not get) a graduate degree in Philosophy, studied for but did not become a minister at a seminary, read and wrote for technical encyclopedias as a day job, taught as a drama instructor at Occidental college…I mean, the list pretty well sums up Leiber’s interests and the themes he explored in his writing. He also had a brief but important correspondence with Lovecraft near the end of the Old Gent’s life, and in many of his memoirs/recollections he attributed much of his development as a writer to HPL’s encouragement and advice. He wrote a lot of great stuff; his 1947 collection, “Night’s Black Agents” is simply one of the best short story collections of the era, in addition to having just the coolest fucking title of all time (a line from Macbeth, Leiber again subtly showing off his erudition).

Unfortunately, like a lot of writers in the post-pulp era, Leiber had a hard time of it financially. He lived in some apparently truly squalid apartments in California, and there’s some great anecdotes from the 70s of Harlan Ellison raging about how Leiber was forced to do his writing on a shitty typewriter propped up over the kitchen sink. Actually, it wasn’t until TSR, the company that made Dungeons & Dragons, licensed the rights to Fafhrd and The Gray Mouser that he was able to live somewhat more securely and comfortably. Frankly, and as we’ll see in today’s story, even if they hadn’t made official Leiber products, TSR 100% should have just been sending checks to Leiber (and Wellman and Vance) because a shockingly large amount of fantasy tabletop roleplaying is taken directly from his work.

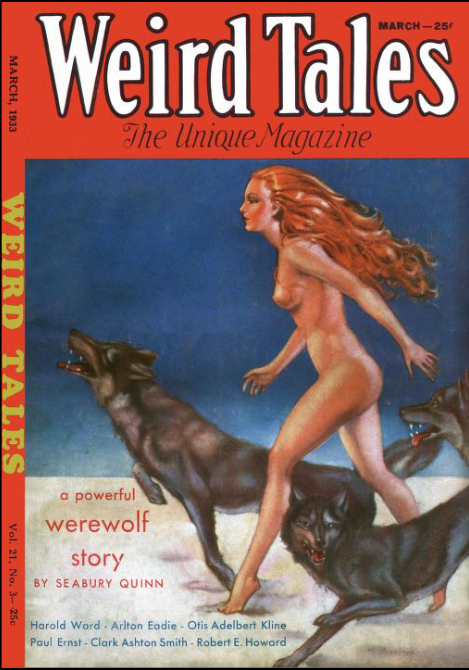

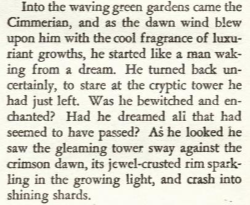

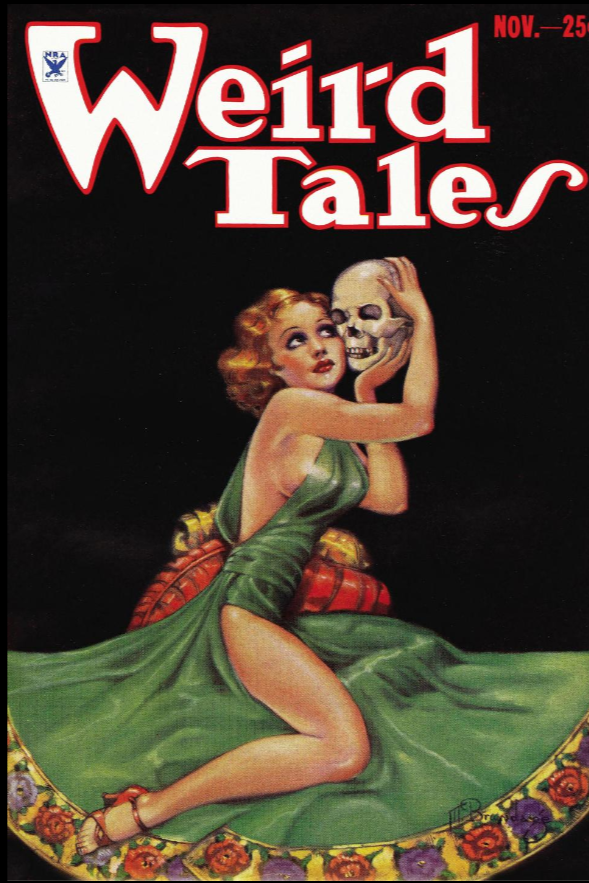

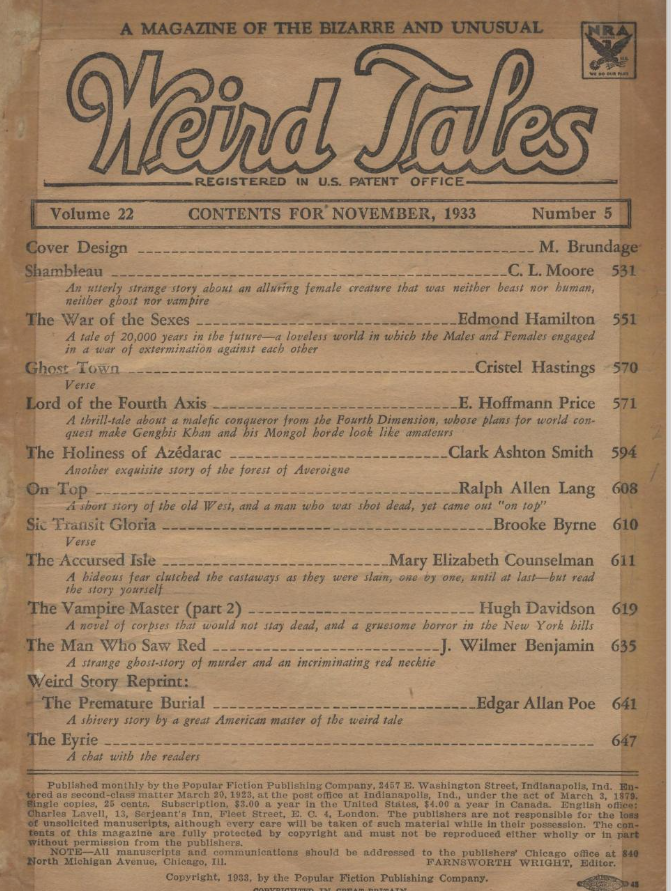

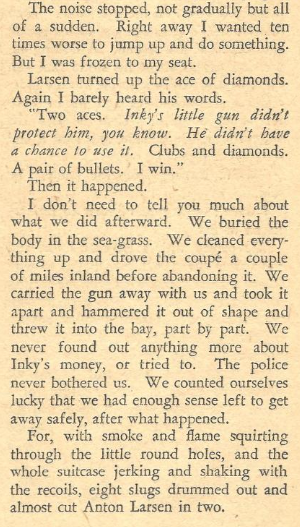

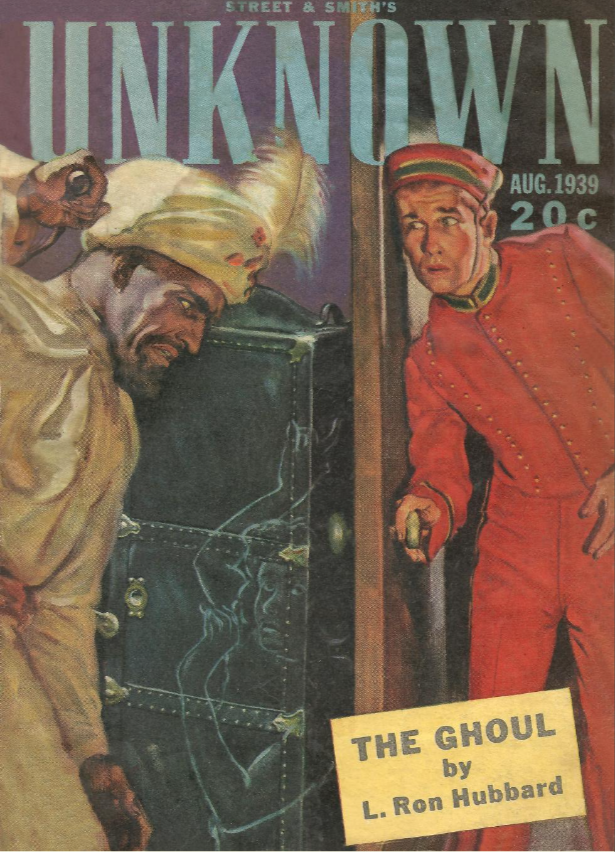

Leiber wrote in a lot of different genres, although you might be surprised at how few times his work showed up in Weird Tales, despite his association with Lovecraft and horror. Case in point, today’s story was published in Unknown, the short-lived fantasy-focused companion to Astounding Science Fiction created and edited by lil’ Johnny W. Campbell himself. Campbell, as we’ve mentioned before, considered himself an intellectual and so he envisioned a a similarly intellectual fantasy magazine that would compete with Weird Tales. Unknown was therefore less lurid, more realistic (or at least the magic and monsters where supposed to be more internally rational), and generally more literary and sophisticated, even going so far as to allow for humor! That said, apparently Campbell would often tell Leiber that his Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories were more like “Weird Tales stories, but…” he would accept them anyway. In fact, no Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story would ever appear in the pages of Weird Tales, which is kind of interesting.

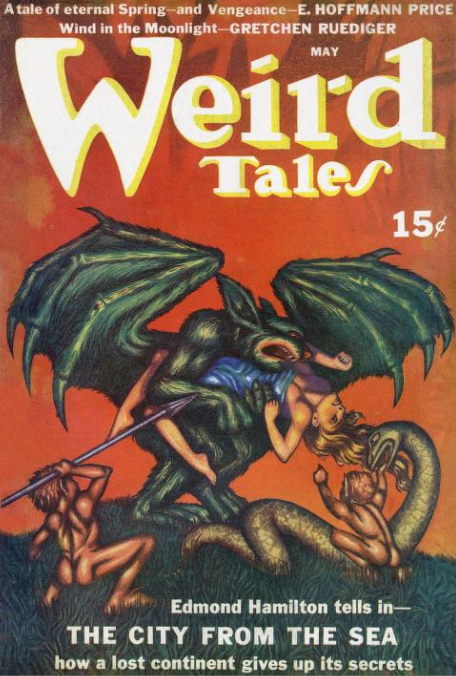

That’s right, the cover of this issue went to Thelemite and future Founder of Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard. It’s a fairly bland cover, in my opinion, kind of lacking the *punch* you’d see in, say, a Brundage cover from Weird Tales. Very much more main stream looking, in my opinion.

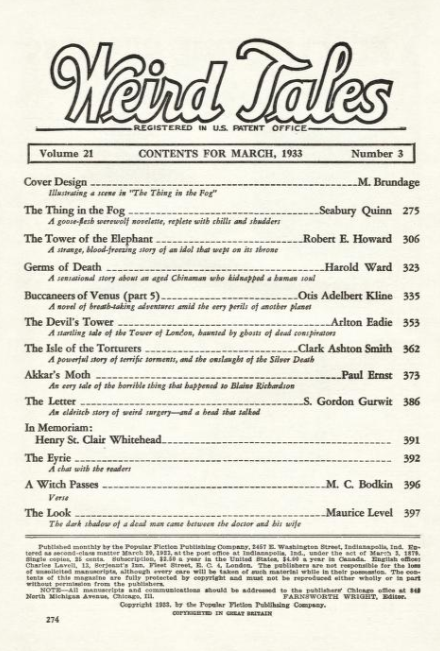

The ToC shows Campbell’s editorial perspective too – fewer stories, but longer. That Hubbard is 90 pages (stretching somewhat the definition of “novel” perhaps, but still…that’s a long ‘un for a magazine)! You’ve got some of Campbell’s heavy hitters here too, del Rey and Kuttner, both important in the pulps and (del Rey as an editor in particular) in the paper back revolution that would come post WWII. Also neat are the two “Readers’ Departments,” integral parts of the participatory fandom that played a huge role in the development of modern genre literature. Unknown had a fun readers’ letters section; taking the title from the famous lines of Omar Khayyam is a very evocative, stylish, and literary thing to do, and the illo is good too:

Very E.C. Comics, isn’t it? But, godammit, let’s get to the story! Fritz Leiber’s first ever published short story AND also the very first adventure of that incomparable duo, Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser!

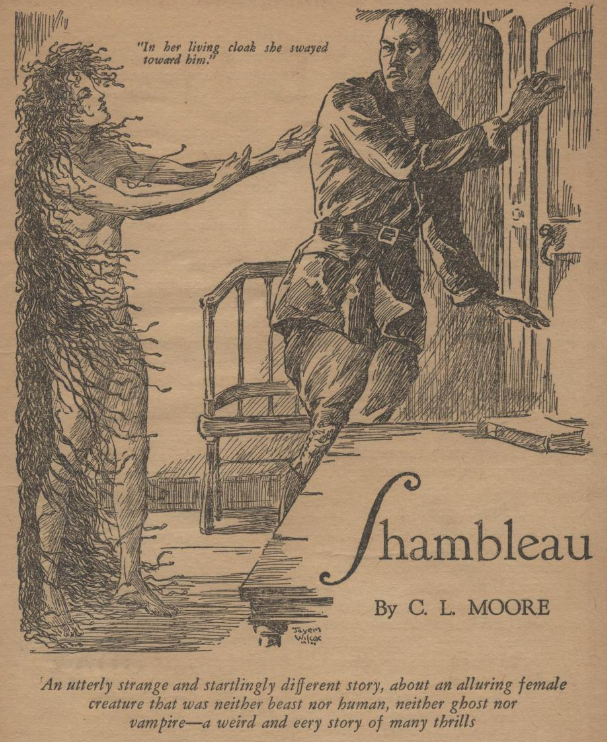

And more comic-book style art, though this time maybe it’s more “Prince Valiant” than “Vault of Horror.” Honestly not really my cup-o-tea, if’n ye ask me…just a fairly bland fantasy scene, though at least Unknown has enough sense NOT to toss in an illustration from the climax of the story right off the bat. Still, I wish the artists had had a little more verve or style or something, especially for such great and visually distinct characters (and situations) that appear here. Oh Well!

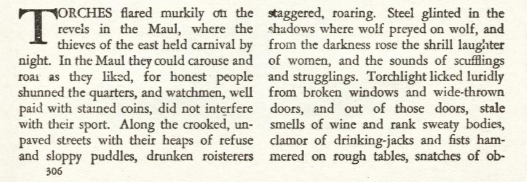

First thing first, I love fantasy calendrics like that…”Year of the Behemoth, Month of the Hedgehog, the Day of the Toad…” it’s just really fun, an easy and striking bit of genre semiotics that immediately shifts the reader into a “fantasy adventure” mode. Leiber keeps ladling on that fantastical flavor with more and more little flourishes, scenes of bucolic yeoman farmers, medieval-esque mercantilism, followed by the promise of a shift-change to astrologers and thieves; it’s great writing that sets a specific scene AS WELL AS positioning the whole of the story within a certain genre-space. And then it’s followed by a couple of paragraphs that introduce the main characters.

The tall northern barbarian is, of course, Fafhrd, while the small dark man is The Gray Mouser. As far as introductions go, these can’t be beat. Their gear, their appearance, their movements, everything is in service of explaining and presenting their characteristics – Fafhrd is a bluff and forthright barbarian in rough linen, bearing a sword and bow, and with a hint of wildness to him, while The Mouser is sneaky, clever, sharp, and secretive. It’s frankly just a perfect intro, efficient and effective.

Of course, we haven’t actually learned their names yet, although that’s not too far off in this story. Still, they’re very well developed and, for the most part, fully formed, the same characters that we’ll meet in their future adventures – this is due to the fact that Leiber, with his friend Harry Fischer (who actually created and named Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, basing them off of Leiber and himself) had been exploring the two and their world for several years already. Leiber in fact had already written several of their adventures already, and that background had practice has given Leiber a good handle on these two.

Anyway, as these two are riding along they’re suddenly ambushed! Bows twang, arrows fly, and the pair spur their horses onward, pursued by a band of eight or so well-armed and similarly equipped ruffians. But, unfortunately for the thugs, these two guys are characters in a sword and sorcery story who have JUST been introduced, so they use this convenient ambush to demonstrate their unparalleled skill and toughness.

Fafhrd executes a flawless Parthian shot and the Mouser zings a leaden ball back at their pursuers, striking two riders down and sending the rest scattering. That done, it’s time we got PROPERLY introduced to these two bad-asses:

There’s a cool efficiency to these two that Leiber likes to play with, particularly in their dialog and the way they speak to each other about what’s going on, always commenting on the action and characters around them. Their friendship is really compelling and very lived in and is, honestly, probably pretty familiar to a lot of people; these two are the kind of friends who, confronted with dangers or troubles, tend to minimize all the challenges they face, kidding around and making fun of the “blundering fools” who would dare challenge them, always talking each other up. It’s a great bit, honestly, and helps reinforce the central idea of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser: they are self-mythologizers that are always confident that they are the main characters in a story. Sometimes this self-awareness comes awfully close to metafictive fourth-wall breaking, but where Hamlet struggles against the role he’s cast in, the Mouser and Fafhrd relish it – they are swashbuckling sword-and-sorcery heroes, the very best possible thing to be, and they’re having a great time (even when they’re not, really).

Having dealt with the ambush, the two realize that this very valley is most likely the one they’ve been searching for. The Mouser unrolls an ancient vellum, and we’re introduced to their quest:

Certainly a taunting tone to Urgaan of Angarngi’s missive, isn’t there? He’s daring treasure-hungry fools to come and face the challenge of his mysterious treasure tower, but that doesn’t daunt these two. Rather, as they ride on, The Mouser reflects on how similarly equipped and armed the ambushers they faced were, suggesting that they might have been Lord Rannarsh’s men. It turns out that the Mouser cut the vellum sheet about the treasure tower out of an ancient book in Rannarsh’s library, and that the Lord, famously avaricious, might’ve taken notice of the theft and sent his boys out to kill them and claim the treasure for himself. Fafhrd scoffs at the idea, which of course means that The Mouser will turn out to be 100% correct.

The two adventurers come across a small cottage not far from the stumpy ruins of the tower, meeting a hilariously taciturn old farmer and his large extended family.

I like the farmer, and the later scenes with his whole family are really great, but for now Fafhrd and The Mouser decide to reconnoiter the tower in the fading light. It takes them a strangely long time to reach the tower, which seemed so close, and when they get there they find a skull and shattered bones just inside the treasure house. A strange sensation of foreboding and danger settles over The Mouser.

Very good foreshadowing, I think; the sense that there is very much something unnatural going on in this treasure tower, something watching and waiting and certainly at least a little sorcerous is conveyed well, but we’re still wondering what exactly is going on.

Heading back to the cabin, the two have a great and boisterous evening with the farmer and his family. Mouser does magic tricks, Fafhrd roars his wild sagas, and they get the whole lot of ’em drunk on wine. It’s probably my favorite scene in the whole story, actually, a wonderful little slice of life scene that really evokes the strangeness of these two adventurers showing up out of nowhere and throwing the normal humdrum pattern of these people’s lives pleasantly off kilter. Leiber is of course just as interested in adventures and swordplay and derring-do as Howard, but he’s ALSO interested in the little material things of life that define the world; his stories are steeped in this kind of rich, lived-in detail, with an interest in the way people spend their downtime. In addition to just being flat-out a lot of fun to read, I think it’s also an important development in sword-and-sorcery literature, a real key moment. Here, back in ’39, Leiber is illustrating to people a kind of “fantasy realism” that uses realistic, naturalistic details to deepen and enrich a secondary world setting.

Of course, it also serves a nice narrative function, because the ancient old man, roused by wine and sing, manages to croak out an enigmatical little statement:

“Maybe beast won’t get you” and then he konks out…great stuff! And it’s echoed again the next day when, striking out early in the morning, they’re stopped by the gangly and shy farmer’s daughter, who has a warning for them.

This family of farmers live right next door to a death trap, apparently, and have learned to give the place a wide berth and keep a respectful distance. I really like how Leiber uses the peasants here – again, they have had to live next to this tower. Whatever danger dwells within, they’ve learned how to avoid it, getting on with their own life in the shadow of its threat. It’s only interlopers and outsiders who blunder into the tower who get killed. It’s a fun, subtle inversion of what a fantasy hero armed with cunning and expertise and knowledge and all that.

But of course no warning, no matter how blood-curdling or threatening, would cause Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser to turn aside from a quest. They continue on through the woods, reflecting merrily (and perhaps a bit unconvincingly) on the remarkable imagination of the farmer’s daughter. Then they meet a very material threat: the men who had ambushed them yesterday have regrouped and reformed at the tower. It’s obvious that they know about the treasures rumored to kept in there, since they’ve also brought shovels and picks.

There’s a long (and good!) scene of sneaking and combat, with Fafhrd and The Mouser getting the drop on these guys. Now, I find the “Fantasy Combat Discourse” generally pretty boring, but I DO like the way Leiber does his fights. To be fair, if you’re one of those HEMA nerds who pours over fechtbücher and owns a broadsword, you’re going to be annoyed with Leiber; he’s a fencer, apparently a very good one, and so the way his heroes fight is very much informed by that. In particular, Fafhrd tends to wield his enormous sword a lot like a rapier, something that might strike some as silly. Deal with it, though, is all I can say, because the combat in this section is fun, and also better than any swordplay that Howard wrote – Conan might hew his way through twenty dudes, but Fafhrd is having to be realistically careful fighting two guys who have him flanked. There’s a sharper sense of danger, is what I’m getting at, probably because Leiber at least has a sense from actual fencing practice about the ways someone can get overextended or leave themselves vulnerable. Makes his fighting descriptions that much scrappier, I think.

A certain red-haired fellow among the ambushers confirms what The Mouser had suspected: these were Rannarsh’s men, and the venal lord had certainly hoped to get the fabled gems himself. Following the battle, there’s a great bit of Fafhrd barbarism – the combat over, becomes first almost hysterically hilarious, and then deeply, almost ridiculously, solemn about a man he’d just killed.

This is contrasted with The Mouser’s own reaction – he may be feeling a little sick and anxious now, but he knows that the force of the combat won’t come on him for some time. It’s another of these Leiber flourishes, a deep and abiding interest in the interiority of his characters and the often very different ways people can react to or experience extreme things. It is simultaneously taking a part in and commenting on the Howardian tropes of sword-and-sorcery, in particular the way Fafhrd’s barbarism is being contrasted with The Mouser’s more urbane reaction.

Entering the tower, The Mouser is relieved that he no longer feels the dread that had oppressed him the night before. They explore the first chamber of the tower, and run across more smashed skeletons – it seems like something indeed has been pulverizing interlopers here, although it may have been a very long time ago. Interestingly, however, the two find a scroll case on one of the corpses that includes a note very similar to their own!

This note, along with the many other skeletons strewn about Urgaan’s treasure house, reveal the truth: the dude has made some kind of death trap, and is luring people here with tales of unbelievable treasures.

Undeterred, the two advance up the stairs, determined to search out discover the treasure. As they reach the top of the stairs, steel glitters in the dark as a knife is hurled from a doorway, nicking the Mouser in the shoulder! Enraged, he darts into the room, sword drawn, and discovers Lord Rannarsh hiding there.

Unmanned by fear, Rannarsh seems only to be interested in escaping, even abandoning all claims to the treasure. However, confronted by his hated enemies, he masters himself enough to try a second dagger, which earns him a skewering at the hands of The Gray Mouser. Following his death, Fafhrd muses on how Rannarsh seemed to be seeking death, which The Mouser says was simply because he had appeared weak and afraid in front of witnesses. It’s another trademark of this duo, always willing to believe that others are as awed of them as they are of themselves, conveniently ignoring all other contradicting information, like when Rannash refered to a “thing” that had been playing “cat and mouse” with him. But, just as The Mouser makes this pronouncement, a sudden and horrific pall of fear falls upon them!

Having failed their saving throw vs fear, the two of them are frozen to the spot, listening to the steady footfall of someone approaching through the tower, up the stairs, and coming towards them. Eventually, a new NPC is introduced, an ancient looking holy man who looks grimly over the room before greeting them.

This man is Arvlan, a direct descendant of Urgaan, here to destroy the horror that his ancestor has left behind. Not letting them speak, Arvlan explains his purpose and history, and then sweeps out of the room on his holy mission.

Arvlan, we hardly knew ye! But, interestingly, once Arvlan gets mashed offscreen, the paralyzing fear that had held the two of them in thrall lifts, and they’re able to move again. Swords out, they rush into the room and see the red ruin left behind of the holy man, crushed and splattered in the middle of the room. But their attention is soon drawn away from the corpse and towards a stone marked with the words “Here rests the treasure of Urgaan of Angarngi.”

The two of them set to work, using pick, mattock, and pry-bar to begin their excavations. Weirdly, they quickly encounter some kind of strange, tarry substance in among the masonry, though not even that gives them pause; they keep gauging away, eventually exposing enough of raw stone that they can get their pry-bar in and wiggle it around, loosening and gouging alternatively. As they keep at the work, though, a new strange feeling of revulsion comes over The Mouser, a sensation clearly related to this dark, foul smelling glop that they’re working on. Nauseated, he goes to a window for a breath of fresh air, and sees down below them the farmer’s daughter. The young girl is clearly trying to screw her courage to the sticking place to come in and warn them of their danger.

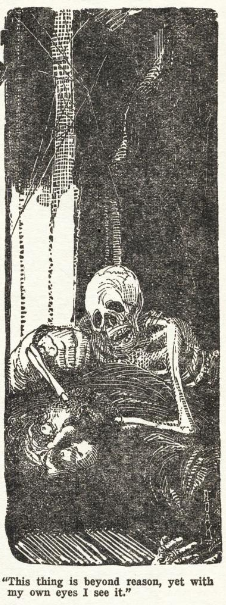

A kind of mania descends on everyone now – The Mouser has seen something in the ceiling, but he can’t articulate it even to himself, and instead lurches sick and fearful out of the room, focused only on keeping the girl from entering the tower. Meanwhile, Fafhrd seems possessed, blind and deaf to everything else expect the stone that hides the treasure. Like the weird fear aura the place had earlier, it seems like the tower is projecting some kind of weird psychic effect, and everyone is mostly powerless to resist it. As the Mouser reaches the bottom of the stairs, his muddled mind steadies itself enough to realize that what he’d seen on the ceiling was a corresponding smear of gore, the counterpart to the blood on the floor. What could it mean!? And why is the tower suddenly vibrating!?

Meanwhile, Fafhrd has finally cracked into the treasure chest!

In the moment, this is all extremely strange and weird and not entirely clear. A weird basin full of dark celestial mercury, upon which floats a weird tangle of glittering geometric shapes, including the huge diamond promised in Urgaan’s message. Everything sparkles with a strange inner light, and Fafhrd weirdly seems to sense that he’s gripping a piece of a thinking mind in his hand as he grabs for the diamond. Meanwhile, the tower is beginning to twist and undulate; The Mouser thinks at first it is toppling, but he realizes there’re no fissures or breaks…rather, it’s like it’s wiggling or bending! Back in the treasure chamber, the weird gems start jittering in the black mercury, and Fafhrd is having a hard time holding on to the skull-sized diamond in his hand. Doors and windows begin to clamp shut, closing like a sphincter, and Fafhrd realizes that the room itself is changing shape.

The Mouser reaches the girl, and they dive for safety beyond the clearing outside of the tower, while Fafhrd confronts the realization that, basically, he’s inside an insane robot.

The diamond, strangely mobile and very hostile, flings itself at Fafhrd’s own skull as he tries to escape, eventually exploding into a cloud of sparkling dust. At that, the tower begins its death throes, with Fafhrd only just escaping before the door slams hut.

There’s a break in the story, resuming after some time has passed.

And that’s the end of the story!

It’s a pretty strange one, isn’t it? I think it’s true to Leiber’s own proclivities, but you can see the Campbellian “rationality” in the tower/robot. Urgaan’s tower is not merely magical; it’s some kind of weird magical technology, complete with what is obviously a kind of high-tech gem-based brain. Presumably, Urgaan has built this conscious robotower as some kind of horrible death trap – lured in, the computer then smooshes all interlopers, it’s weird stone body lubricated by that odd tarry goop. It’s a fun and fully bonkers idea, although it’s not too wildly different from Howard’s magic, which is often more occulto-scientific that pure magic. Why Urgaan would do that is left mysterious, which is actually kind of fun – people can be real assholes, and if you’re some kind of ancient technomancer then maybe that’s the sort of the thing you’d do!

You can also really see the influence Leiber had on Dungeons and Dragons in this story, too. It’s almost exactly the kind of thing Gary Gygax would write, right down to the dungeon built around a weirdly complex and almost certainly fatal death trap. But even beyond the setting and the trappings of the dungeon, I think you get a sense that Gygax et al. ALSO certainly styled their adventurers after Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser.

And it’s the characters of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser that are so important and foundational to the genre, in my opinion. Even Conan at his most avaricious (say, in “The Jewels of Ghwalur”) ends up shifting gears, exploring a mystery, saving a girl, and engaging in heroics, whereas Fafhrd and The Gray Mouser are almost single-mindedly focused on this tower, ignoring countless warnings and obvious signs that something is amiss. That stubbornness and single-minded selfishness is key to their motivation and characters, and Leiber is really the first writer of the genre to really explore that aspect of sword-and-sorcery. Even though they envision themselves as heroes, any actual heroism that they end up doing is often in spite of themselves. It’s often funny, although only rarely does Leiber play that purely for laughs; rather, their self-importance and unassailable confidence gives them the boost they need to persevere in the face of insane odds. Mostly, Leiber is interested in the way these characters, who clearly see themselves in a certain light, are actually a little more complicated and gray than we might expect. Particularly in the post-Howard world, most of the sword and sorcery heroes are painfully noble barbarians; guys like Elak of Atlantis are even Kings who (despite renouncing a throne) always carry with them a sense of portentousness and destiny. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are different, wanderers and adventurers and thieves, just a couple of scrappy normal dudes who are going to carve their destiny and wealth out of the carcass of the world. Fafhrd and The Gray Mouser are an interesting counterpart to Conan and Jirel, and represent a key part of the evolution of the genre.