It’s thanksgiving week here in the states, a time of deep tradition when people gather with their loved ones to discuss the classic pulp stories that mean something to them. And so, in keeping with the ancient custom, I would like to offer up a heapin’ helpin’ of one of my favorite short stories of all time, C.L. Moore’s unbelievably amazing “No Woman Born,” originally published in Astounding Science Fiction in December 1944.

Now, for all of these pulp strainer things, I’ve been linking to the stories in the actual magazines over at archive dot org (huge thank you to them, for real! Long Live Archive Dot Org!), and I hope ya’ll have been taking the time to go and read ’em. For this one, though, I really Really REALLY want to encourage you to stop right now and go and read through the whole story. Seriously; right now. Do it.

The reason why I want ya’ll to go and read it is because the act of reading it yourself is, I think, an integral part of the story. Watching a story unfold blindly is always the ideal, of course, but I think Moore really uses the “surprise” of the ending to force the reader to confront their preconceptions and expectations, and it is absolutely integral to this piece of fiction. I truly believe that this is one of the great short stories, full stop, regardless of genre or period or whatever – it’s that good, and I want you to get the full effect! So here’s the link again: go read “No Woman Born” before inflicting my long ass rambling on yourself!

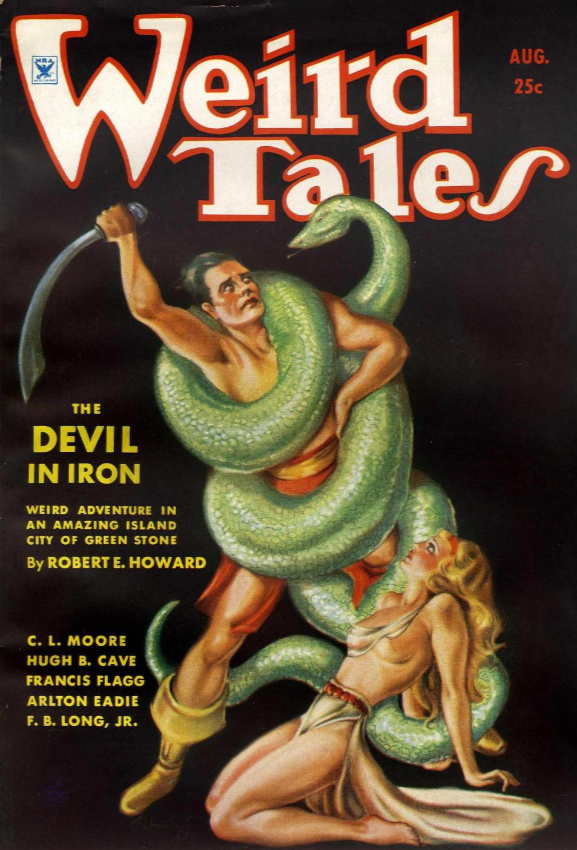

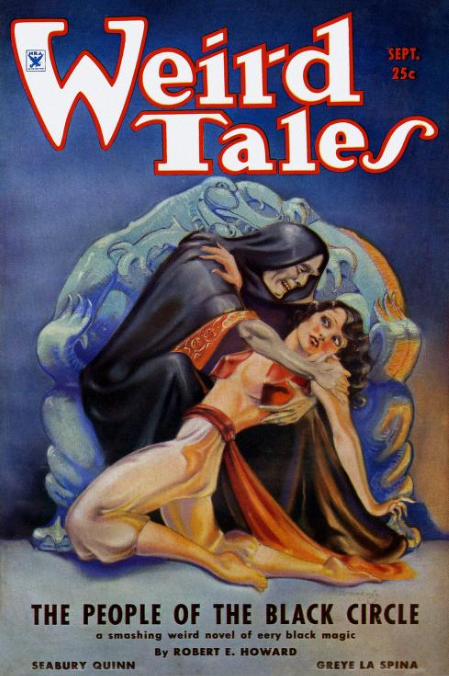

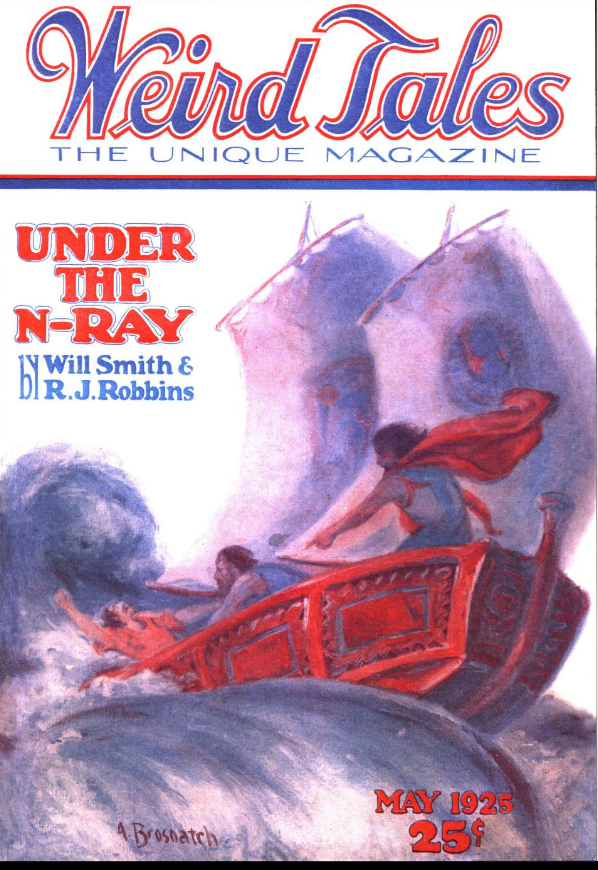

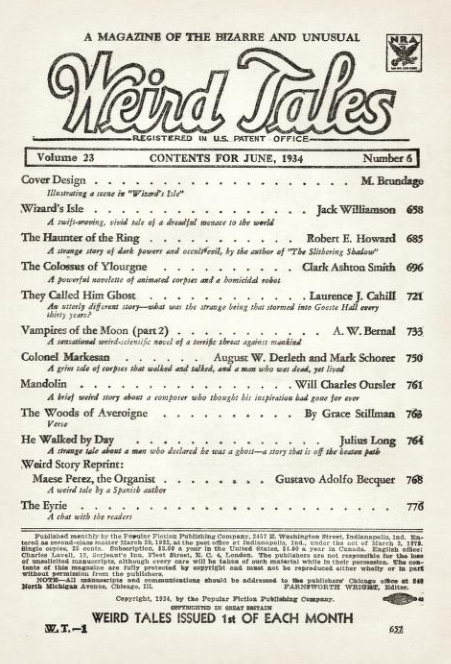

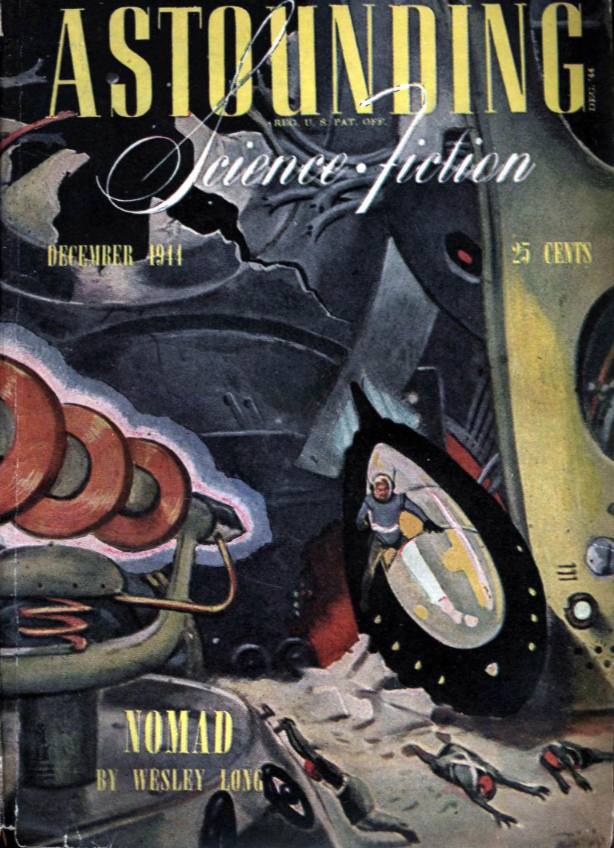

We’re taking a brief excursion out of the pages of Weird Tales this week, since Moore’s story was published in what was at the time the preeminent science fiction magazine in the world. The history of this magazine is fascinating, and it’s played a huge role in the development of the genre, so let’s take a moment to talk about it, shall we?

Astounding was one of the first real competitors with Gernsback’s Amazing, and by the 40s had established itself as the high-brow and most literary of the sci-fi pulps. Astounding was first published in 1930, just four years after Amazing had named (and created!) the genre of science fiction in 1926. In that first iteration, Astounding had puttered along until going bankrupt in 1933, when it was bought up by the gigantic and powerful magazine publishing firm of Street & Smith. This was portentous, as S&S had been in the magazine game for a while and had built up a really potent distribution network for their already immensely popular pulps like The Shadow and Doc Savage. Astounding benefited hugely from this expanded reach and it quickly outsold other magazines like Amazing and Wonder Stories to become THE sci-fi magazine.

The other thing that Astounding had going for it was an interesting and, frankly, visionary editorial culture. Under S&S’s reorganization of their newly acquired magazines, they moved F. Olin Tremaine and Desmond Halls from some crime pulps over to Astounding; these two were an enterprising and energetic team of editors who would end up encouraging writers to experiment with new topics, styles, and ideas. In particular, Tremaine famously wrote the “thought-variant” editorial in the Dec 1933 issue’s “Brass Tacks” that has become famous in the history of sci-fi:

These “thought-variant” stories, as Tremaine calls them, are explicitly interested in “social science, the present condition of the world, and the future.” Furthermore, they are necessary as a corrective to any possible stagnation in the genre, what Tremaine refers to as “habit-ridden” or “grooved” stories. The upswing of this is a move, in part, away from two-fisted space adventure stories towards more thoughtful, meditative, and “logical fantasy” type interrogations of society and culture under speculative conditions. This actually set the stage for a huge split in fandom in the 40s that was basically the exact same bullshit that happened with the fascist “sick puppies” in sci-fi a few years ago. Anticipating the exact same nonsense, basically the fans of heroic, red-blooded, ray-guns-and-space-opera stories thought that the pinko psychologizers over at Astounding had RUINED science fiction with all their navel-gazing and social commentary; these reactionary sci-fi fans found a home in the 40s and 50s over at Amazing Stories under Ray Palmer, who embraced rampant nationalism and militarism as a lucrative literary virtue.

Maybe I’ll talk about that in the future, but what’s important here is that Astounding in the 30s had envisioned a new and different approach to sci-fi, one that would come to dominate the genre eventually. It’s no wonder that C.L. Moore was able to place a work like “No Woman Born” in the magazine in ’44, since it is almost exactly the sort of story that defines this new, more cerebral approach. Of course, by that time Tremaine had been pushed out and replaced with arguably one of the most important figures in the history of science fiction, John W. Campbell. Jr.

Campbell is a wildly interesting figure and his influence on sci-fi is uncontested; he basically single-handedly created what we think of as the “golden age” of sci-fi over at Astounding, where he published Asimov, Sturgeon, Clarke, and Heinlein and effectively made their careers. Even into the 50s, when magazines like Galaxy and paperbacks basically overtook both him and his magazine, Campbell retained a tight grip as a powerful taste-maker in the genre and was a major player in fandom and the early conferences. He was also a vile and life-long unrepentant racist, famously rejecting in the 60s Samuel R. Delany’s novel Nova because he didn’t think a black protagonist was believable or palatable to audiences, and who wrote several truly reprehensible essays in defense of slavery and segregation. He was also an early dianetics/scientology guy, and was big into pseudoscience (particularly psychic phenomena). But, weird racism, dumb psychic shit, and “western civ” chauvinism” aside, as an editor Campbell was definitely in-step with the Tremaine program of “thought variant” style sci-fi, often pushing his writers to explore the social, cultural, and historical implications of the ideas and concepts they were inventing.

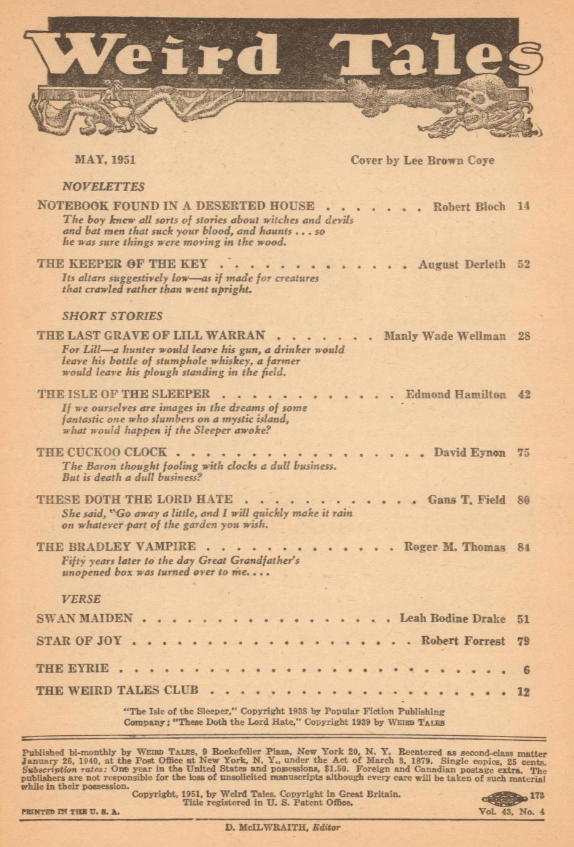

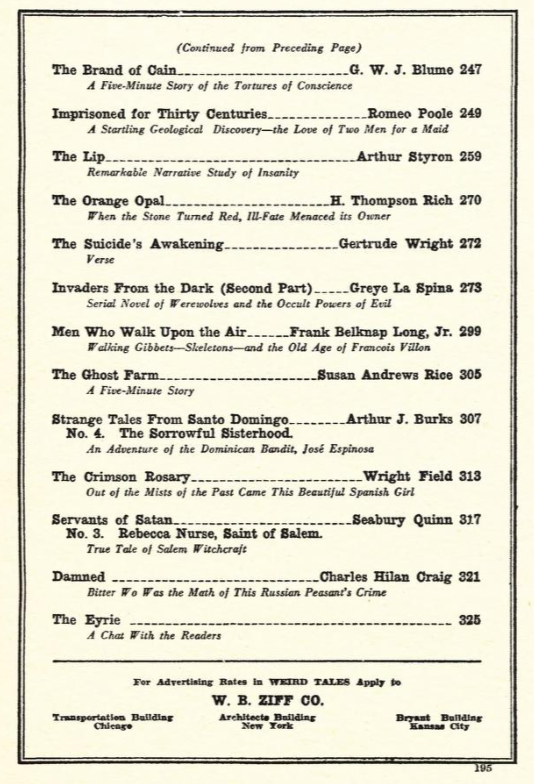

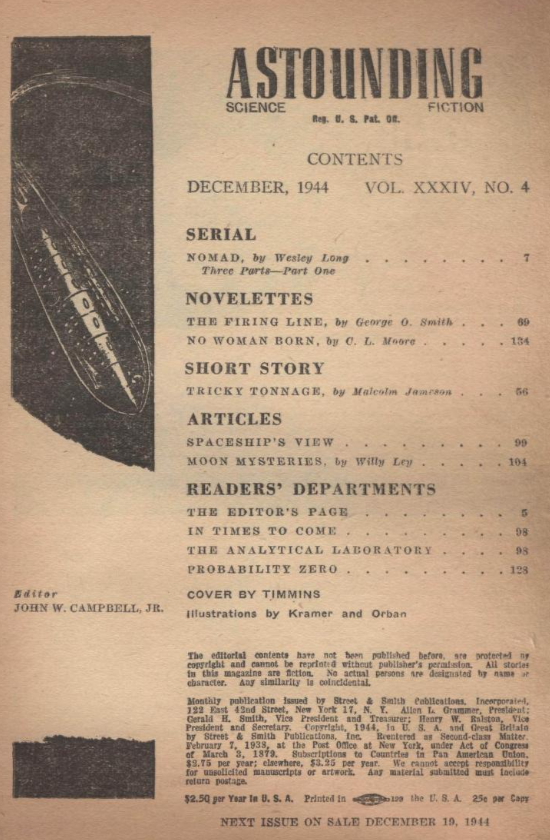

Now, the ToC of this issue:

Kind of neat to see the different philosophies at work in the magazines at the time. Sci-fi, which had a history from the 20s of orienting itself explicitly with “improving” literatures, maintained a tradition of printing pop science articles right alongside the fiction in the pulps. It’s also important to note the large amount of communication opportunities available to the fans – this participatory fandom is a major part of both the success of these magazines as well as the genres themselves. Not much else to say about the other authors on here, except for George O. Smith; he wrote a fun series called the “Venus Equilateral” stories that dealt with a manned communication satellite that I recall being a lot of fun, BUT more hilariously he’s the guy that John W. Campbell’s wife Doña left him for in 1949.

But enough rambling about all that. Let’s ramble about “No Woman Born” instead!

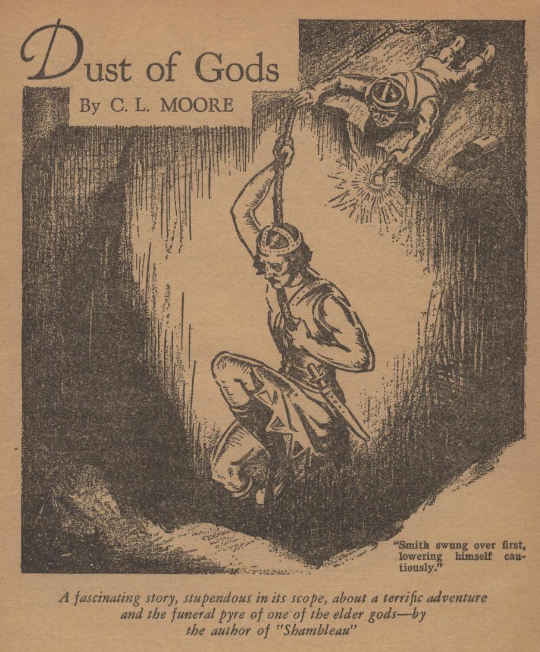

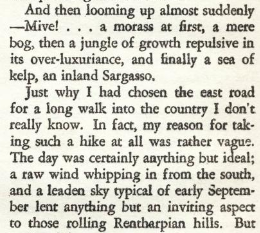

Great title illustration, nice clean classic sci-fi: what looks like some kind of video projector with a Lovely Lady on it, while the grizzled scientist is tinkering with his robot parts, a noggin, a foot, some springs and wires. The story summary only partially and weakly sets up the story, but you get the gist of it – a beautiful woman died in a fire, but now has been resurrected as a robot.

Three paragraphs in, and we still haven’t learned this woman’s name, but we get a lot of loving and highly sexualized memories of her; the fabulous grace of her wonderful dancer’s body, he sexy-as-hell voice, all through the mind’s eye of her manager, John Harris.

She is, or was, Deirdre, a star who surpassed even Sarah Bernhardt and Lille Langtry in terms of exposure, fame, and adulation. Again, through Harris’s reflection, we’re given a glimpse of Deirdre’s beauty as a product of her grace and movement and charisma, a “lovely, languorous body” that the world had known and studied and adored…it’s a deeply voyeuristic kind of fame, very much Deirdre being sold as product. It also focuses on the body and Deirdre’s physicality and the dynamism of her movements.

This is the first of many allusions that Moore makes in a story dense with ’em. This one gives us some insight into Deirdre’s name, and might also offer a clue to where the story is going (although if you follow it slavishly, you’re in for a surprise). But the Deirdre of Stephen’s poem is Deirdre of the Sorrows, “The Irish Helen,” a woman so beautiful and desirable that she led to war and destruction. After a series of slaughters and betrayals, she’s basically kidnapped by and forced to marry the King of Ulster, Conchobar mac Nessa. But after a whole year of never smiling, rarely eating, and generally being a huge vibe killer to Conchobar, the King demands to know who, other than himself, she hates the most. She names the murderer of her original betrothed, and Conchobar says he is going to give Deirdre to him. In protest, she hurls herself from Conchobar’s chariot, dashing her head against a rock and dying. It’s a story of a woman defined by her beauty, possessed and powerless in the hands of men, and whose only recourse in the end is to die.

The Deirdre of “No Woman Born” has died in a theater fire, however, and now Harris is arriving at some skyscraper laboratory to meet the scientist who has, for the past year, been attempting a technological resurrection. From the italicized summary under the title, we know that Deirdre has been turned into a, basically, a robot (although we’d call her a cyborg today, since her physical human brain has been incased a robotic body, but that’s neither here nor there). The scientist, Maltzer, had apparently been on the scene of the fire and had persuaded Harris to allow him to, basically, build a a new body for Deirdre, a task that took a year to complete and has, apparently, left Maltzer something of a mess!

Something is bothering Maltzer; before he lets Harris go to meet her, he wants to have a talk. What comes of it is this: Maltzer believes in the technical perfection of the work, the body he’s built and the connection between it and the brain, but he’s afraid of what he’s done. He’s been so close, so intimate, with Deirdre’s new body, that he’s not sure he can judge whether its “good” or not – he’s afraid that Deirdre, used to adoration and being a beautiful woman, might find adjustment in her new body difficult, and that rejection could be disastrous for her psyche. Again, it’s focusing on the body, on how bodies are perceived and experienced.

But Harris screws his courage to the sticking post and goes on in to meet Deirdre. It’s a sitting room, tastefully appointed, with a high-backed chair in front of the crackling glow of a fire. And in the chair is Deirdre.

This section is really great, a very considered and thoughtful meditation on memory and perception and the way the brain orders and sorts and categorized images, all focused on Harris trying to make sense of the robot before him, seeing first just the machine, then the memory of Deirdre, before finally and laboriously combining the two into the cyborg standing before him.

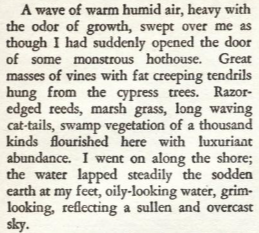

The key thing for Harris here is her voice and her movements – after that first hiccup with her voice, he recognizes the same trills and sounds and mannerisms in her speaking that he remembers, perfectly reproduced and executed. Similarly, her grace and movements, even in so alien a body, are Deirdre’s. Even faceless, and with jointless arms and legs made from hoops of metal, her new body is clearly hers. Moore’s description and appreciation of the body and movement and physicality is one of her (many) strengths as a writer, something that I feel like she developed and took from her sword and sorcery writing (a genre preoccupied with describing and considering the body and its potential). It gives this robot a reality that I don’t think I’ve ever really seen before (or since) in science fiction. I feel like the editors and illustrators must’ve felt the same way, because there’re some great drawings of Deirdre throughout the story:

The other aspect of Deirdre that’s so well done in this story is her expertise – she’s an expert dancer and entertainer, with years and years of training. Her discipline and the muscular coordination it forced her to develop have clearly played a part in how effectively she’s been able adapt to this new body, learning to control it with the same effortlessness that she moved around with her old human body. Similarly, there’s the sense that her ability to perform for an audience might play a role here – she is in a strange costume, playing the part of “Deirdre.”

She tries to convey the strangeness of her experience to Harris (and us, by extension), though it’s not clear that her former manager is getting all she’s putting out. There’s also a hugely important part of the story where she describes her realization that her body is like a ship or a plane (or a gun):

That’s incredible stuff – she’s talking about machines and the perception of the men who use them, but it also holds true for women in the eyes of men. Men conceive of their ships and planes and guns as “she” – is that any different than how men create and impart images onto the actual women in their lives? And now here’s Deirdre who is both a woman and a man-made machine.

She announces to Harris that she is going to go back on the stage, immediately in fact, that very day, an act in a hugely popular variety show that has been kept secret from almost everyone. But Harris is suddenly worried that Maltzer might’ve been right.

This is the core of the fear that Maltzer and Harris have: is Deirdre still trapped in the past, with an image of herself as a Real Woman, and is her reality, as a Robot, going to crash into that fatally?

It’s made even more explicit when Maltzer and Harris are watching the show that evening – it’s a variety show, so there’re lots of acts on before Deirdre, and of course its full of beautiful women is gorgeous costumes. And for Malzter, that get’s to the crux of the problem:

I mean, yikes huh? A woman’s role in society is a function of her femininity, and of course Deirdre is no longer a woman, right? How is she supposed to navigate a world where she is so utterly and irrevocably divorced from it, particularly when she ridiculously persists in pretending like she IS a woman? This is some really keen, sharp, insightful writing from a woman who was, of course, constantly navigating many deeply sexist and essentialist societies and milieus.

And for Maltzer, Deirdre’s separation from her organic body has deeper implications – she has, of course, lost all senses except for sight and hearing. These are the “coldest” of the senses, the least deeply human of them. Taste, smell, touch – these are vital animal experiences and, diminished by their loss, Deirdre is fundamentally less human.

Just want to point out that Abelard reference, which reinforces Maltzer’s idea that sex and humanity are intimately and fundamentally tied, and that the neutering of a being’s gender is a kind of dehumanization.

The variety show goes off without a hitch; in fact, it’s a huge success. Deirdre hypnotizes the audience, her dancing and singing a remarkable display of artistry and soul that leaves them in rapturous adulation, just like before the accident. But Maltzer STILL isn’t convinced – he KNOWS that at some point the novelty will wear off and that they will turn on her, treat her as a machine or a freak, and in doing so they will destroy her. Also, Maltzer feels that, because of his intimate relationship he shares with Deirdre as the builder of her body, he KNOWS that she is also worried about something, scared of something. For Maltzer, this is enough – he knows that she’s afraid of the same thing that he is, that she knows she is less-than-human, alienated from all that is human forever. Because of that, Maltzer declares that he MUST put a stop to all this nonsense! Deirdre must get her to a nunnery!

Harris leaves, and Maltzer and Deirdre have a long discussion about the future – no decisions are made, but Deirdre agrees to a two-week break in the New Jersey countryside while Maltzer, wound to the breaking point, will go to a sanitarium. They’ll rest and recuperate, and then they will all meet up and come to some kind of conclusion.

The three come together in two weeks, meeting at Maltzer’s skyscraper penthouse lab apartment thing. But Maltzer and Deirdre both are more resolute in their convictions than before. But to Harris, something is off with Deirdre:

Maltzer makes one final attempt to convince Deirdre that she cannot go back on the stage, that she must retire and live out the rest of her life in seclusion – she is too different from humanity, she can never fulfil the feminine vanity and womanly urges that she has because she is simply no longer a woman. Maltzer is remorseful, feeling that he has done her a disservice by preserving her life in a form so obviously hateful and alienating. And he knows that Deirdre knows this! He knows that she is troubled by something profound and deep, perhaps worse after the two weeks on her own! But she refuses to admit that to him, saying that she is fine, and that she intends to get back onto the stage.

And so Maltzer climbs to the edge of an open window and threatens to kill himself if she doesn’t acknowledge that he’s right and do what he says.

Harris watches as Deirdre, seemingly powerless, is getting harangued by Maltzer, who again is in an open window threatening to kill himself because she won’t accept the FACT that he is RIGHT about everything. It’s great stuff!

This is a really incredible part of the story, but I’m not going to reproduce it – sufficed to say, Deirdre explains that Maltzer’s analogy-by-frankenstein is flawed. She’s not a monster, and he didn’t create her, merely preserved her. Her brain is her own, and the way it operates the body is ALSO her own. She also does a neat thing where, while she’s talking, she’s fiddling with a cigarette, acting like she’s smoking, and its only when she flicks the unlit cigarette away and laughs that Harris and Maltzer realize that the whole time she’d been talking they’d believed she’d been smoking. Deirdre says that this is a testament to her humanity and ability to fit in, but Maltzer calls it a trick and says she doesn’t understand, not really; she IS a monter, his monster, and he must pay for the sin he has committed in creating a subhuman that dreams it is human.

Maltzer is poised to kill himself, when, suddenly, Deirdre blazes.

She moves like lightning across the room, with speed that perhaps is more than simple motion – to Harris, it is like she is moving impossibly fast, perhaps in some kind of strange, fourth-dimensional way existing in two places at once. Then time seems to return to normal, and she is easily lifting Maltzer and carrying him like a baby back across the room and depositing him on a couch. But Maltzer is STILL dumb as hell and hasn’t figured it out!

Deirdre demonstrates that she can produce sound vibrations powerful enough to shake the building. She is, in fact, unbelievably powerful as a result of some kind of emergent property that is the result of her own brain’s ability to seamlessly and perfectly interface with this strange robotic body. That is the source of her discomfort – not that she is subhuman, but that she has transcended humanity, that she is moving so far beyond it that she is in danger of leaving it behind entirely!

What has she learned? Divorced from her old body, forced to look inwards and cultivate strength and talents she never knew she had, she must’ve learned something about herself, how she used to fit into the world, and how she would fit into it now? And what about us, about humanity itself – outside of it, she sees its little vanities and the weaknesses. And Maltzer, with his myopic ideas and inability to conceive of Deirdre as anything more than an enfeebled half-woman locked in a body that, sexless, cannot give her the satisfaction of the Feminine Ideal as he sees it. She sees through all that from her new perch, becoming fully transformed, maybe the first expression of real transhumanism I’ve ever seen in sci-fi.

She get’s Maltzer to admit that he doubts he could reproduce her – something about her brain (which, she explains, is developing new senses beyond the paltry human five) with its training and discipline and idiosyncrasies has forced the body to work in this way. And so she is alone, singular, on the edge of something profound and transformational. That is why she wants to keep going on the stage and performing; it gives her a connection to humanity, something that she could so easily cast aside.

And that’s the end, Deirdre standing on the precipice, contemplating her existence and what it means. I take the ending to mean that, for the first time, Deirdre is realizing that she is the one who will make the decision, that she has to confront and take control of her own life, away from all the little men that had surrounded her before. And, of course, she is realizing that she is changing so much – already, in two weeks time, she has become basically a god. What will she be in forty years? Even the limitation of having a human brain might be surpassed in that time, but there’s the fear, the problem that she’ll have to confront: will she be human at the end of this process?

This is just such a remarkable story, and its so well written. The whole time you’re seeing Deirdre through the flawed eyes of these men, particularly Maltzer who, Pygmalion-like, thinks he has some ownership or, at least, insight into this thing that he’s created. But Deirdre is a living being in her own right, and she has come to see the world as it is, not as Maltzer believes it to be. Deirdre, her beauty, her talents, all of these things had been commodified, so much so that Harris and Maltzer (and, by extension, society at large) could not see her as a person with her own agency and thoughts and desires – it took a radical restructuring of her whole being to get there, and even then, she had to DEMONSTRATE her power and abilities to convince them of this new truth. This sudden realization, that these men have had NO IDEA what’s going on, have in fact completely misunderstood the situation, is just such a powerful writerly effect in this story.

I also think the strict sci-fi aspects of this story are great too – I really like the anti-reductionist approach to transhumanism on display here. It is the contingent properties of Deirdre’s brain (and, in particular, her experience as a dancer and an entertainer, it seems) that make all this possible; slap Maltzer’s shit in a robo-body and you’d have something completely different. That’s so much more interesting (and realistic) than the purely digital “I downloaded my consciousness into a computer!” bullshit you see nowadays, in my opinion. The kind of “wow, psychic stuff!” is maybe a little dated, but it’s par for the course of this era – in the 30s and 40s (and 50s) particularly, a lot of sci-fi writers just took it for granted that OF COURSE new discoveries in the brain would lead to the understanding and utilization of previously unknown mind powers (that’s the premise of most of PKD’s novels, fer chrissake).

It’s just a really remarkable story, written by a woman who had obviously spent some time thinking about these kinds of situations and themes and such. As feminist science fiction it’s almost unparalleled, a remarkable document from 1944 that presages Le Guin and Russ and Tiptree. As literature I think it’s also remarkable – there’s real beauty and insight in this writing, and the way that Moore has constructed a story that is so deep and rich and fulfilling is really a testament to her power as a writer. It’s one of my favorite short stories ever, a phenomenal piece of science fiction that does so much its premise. Anyway, I’ve rattled on and on about it, so I’ll stop here and just say “read more C.L. Moore!”