Know, O Reader, that in the time after the Great Turkey Slaughter and before the sinking of the Year there is a month undreamt of, a month of Sword & Sorcery where the Yule, a time of gigantic mirth and gigantic melancholies, strides forth to tread the jeweled wrapping paper beneath its buckle-booted feet!

Yes, that’s right, it is once again time for my annual celebration of the Best of all Genres, Sword & Sorcery! As I’ve mentioned before, the Xmas season is, for me, the most Heroic and Sorcerous of times, one where I like to kick back and read about the derring-do of various mightily thewed types. And while things have been busy down here in Austin, December has come in like a Nemedian Lion finally, bringing cold temperatures and, with them, a resultant coziness that is PERFECT reading weather. So let’s get to it!

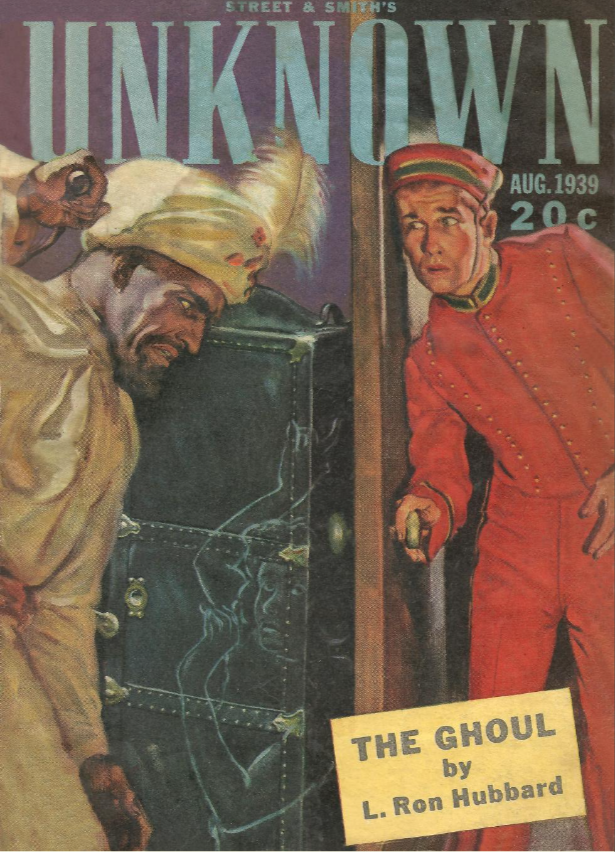

This time around we’ve got a true classic too, foundational in terms of Leiber’s Lankhmar stories AS WELL AS the genre as a whole, for today’s story has the very first example of a fantasy “Thieves Guild” that I’ve ever come across! The idea of organized thieves operating as a cohesive and hierarchical medieval-style guild is a core concept in fantasy, as much a part of the genre as evil wizards and scimitar-wielding bad guys, yet another cornerstone laid by the genre’s greatest mason, Fritz Leiber, Jr. Without further ado, the story this time around is Thieves’ House, from the Feb 1943 issue of Unknown Worlds!

A few years ago, we talked about the very first Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story, “Two Sought Adventure,” and of course we’ve also talked about Leiber as a weird fic writer, so we won’t spend too much time on bio and background. So let’s dive in!

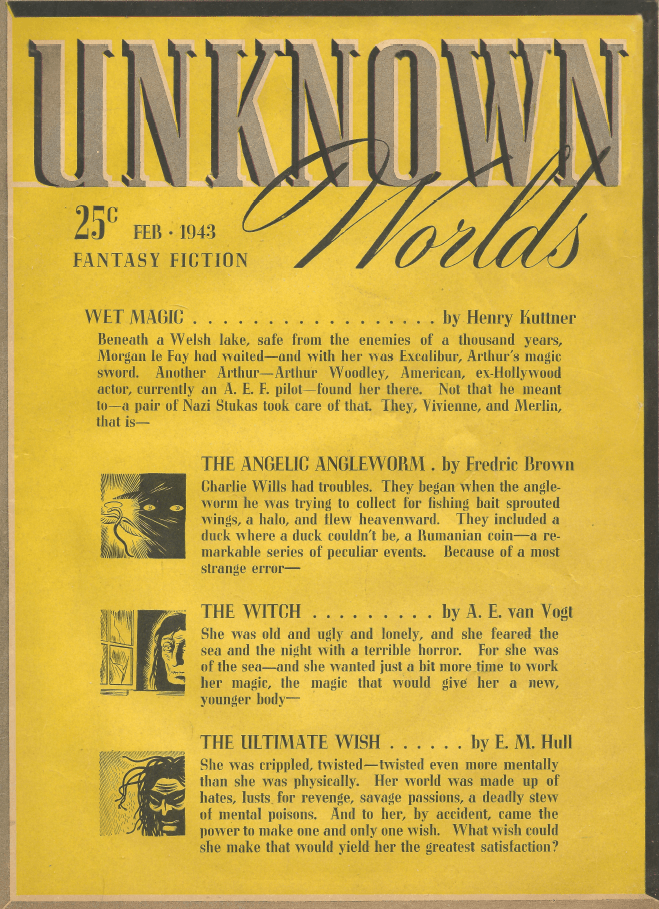

The cover of this issue of Unknown Worlds is a bit underwhelming, huh? I do like the little thumbnails, but it’s hard to imagine that utilitarian little summaries of some of the stories are going to do a better job than a big, crazy cover by one of the many talented artists available for hire at the time. We’re nearing the end of the run for the magazine, though; it’s been losing money for a while and, what with war time paper rationing, it’d soon go under completely, so I imagine the decision to do the covers like this might’ve been influenced by those realities. What’s weird though is that they don’t just put the WHOLE ToC on the cover – these are just a selection of the stories in this issue, plus editor’s columns and letters etc. If you weren’t familiar with the magazine, you might think that all you’re getting for your two bits are these four stories, when, in fact:

A pretty respectable list of work! It’s an odd decision to have only a sampling of the ToC on the cover… maybe based on perceived popularity of the writers, although it seems like a new Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser story should’ve warranted inclusion if that was the case? But, oh well! What is interesting is how Unknown Worlds was really positioning itself as the “fantasy” magazine here. There’s some modern day stuff in here, but a LOT of this issue is devoted to what you’d call classic fantasy, either in the (as-yet-unnamed) sword-and-sorcery genre or in the more broadly defined medieval-ish vein.

Anyway: onto the story!

Title illustration is of a guy getting a back massage from a skeleton, good workmanlike art I’d say, and a fun bit of sword-and-sorcerous menace to start it off – you know something macabre and outre is in the works, but the picture here doesn’t really give anything away, which is good!

An absolutely killer way to start a story, isn’t it? Leiber can really set the hook – a skull with its own name, gilded and gem-encrusted, being discussed by some thieves, and then a brief precis or interior thieves’ memo about the skull of Ohmphal, with a nice little summary of its history AND the difficulties involved in retrieving the stolen item. Really, truly: if you’re interested in the history of tabletop fantasy roleplaying in general and D&D in particular, then you’ve simply gotta read Leiber. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are absolutely the ideal dungeon delvers, and Leiber’s stories lay out so much of the tone and flavor (and, honestly, mechanics) that Gygax and Arneson would mine for their game. The note, the weird factional aspects (with the Priests of Votishal stealing a skull from the Thieves’ Guild), the dungeon-y aspect of the lost temple, and even the need for a well-balanced party – this is a Dungeons & Dragons adventure! Hell, even the format of the memo on the skull is a diegetic DM’s entry, you know what I mean?

Over the next few paragraphs, we get a very nice, efficient explication of these thieves and the “red-haired wench” – they’re mulling over an ancient parchment that the black-bearded boss-thief discovered in a hidden compartment in an ancient chest at the Thieves’ Guild HQ. Now, piqued by the description of the bejeweled skull, they’re planning on liberating the skull of Ohmphal. Fissif, the fat thief, balks a bit at the challenge, though – the hidden temple is a grim and perilous place, and there’s the whole “guardian beast of terrible ferocity” thing too. Luckily, Krovas, master of the Thieves’ Guild, knows just the rogues to help them out:

A double cross! Man, if you can’t trust the Thieves’ Guild…

But what a rousing adventure is in the offing, hey? An ancient crypt, full of traps and ingenious locks, a jewel-skull guarded by a horrific monster, and a planned betrayal. Can’t wait to read about all that, huh? Let’s get RIGHT INTO IT!

Oh, seems like we’ve cut to 25 days later, and we’re suddenly in a foggy, disreputable street somewhere in the winding streets and alleys of Lankhmar. And what’s this fat, scuttling figure making his way to the Thieves’ House?

Fissif, carrying an ancient box and looking a little worse-for-wear, hurries up and slips inside, warning Krovas that “the two” are following quickly! And it’s true, they are, because very shortly we hear a bunch of secretive whistling warnings, and two figures approach!

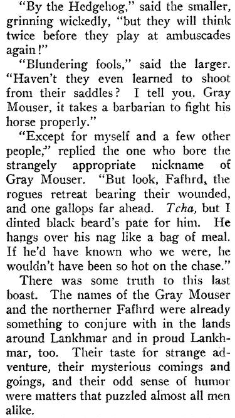

That’s right, it’s our two “heroes,” Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, and they’re hot on the trail of the traitorous Fissif!

We’ve completely skipped over the whole dungeon dive that was introduced in the beginning of the story, leaping directly to the betrayal and its aftermath – it’s a bold, strong choice from Leiber, and the right one too, because while it would be fun to see the Mouser matching wits with ancient traps and Fafhrd slaughtering a horrible monster, the real action is in the betrayal. Leiber’s always much more interested in the way his two adventurers deal with the scrapes, schemes, and hardships they encounter, more so than in the threats themselves – fighting a monster is one thing, but having to chase after a thief who has betrayed these two is where the real meat of the story is at. It’s also reflects Leiber’s interest in urban settings, I think; he passes over a fairly straightforward “dungeon” portion of this story to leap right into the twists and turns of the city, because compared to the wily, evil ways of the city, a dark and dangerous dungeon is nothing!

There’s also a great example of what is one of the most fun parts of these two characters: the dialog between Fafhrd and the Mouser. Both characters have very clear voices, with very well-developed perspectives, and the comradely rapport between them is always great and often quite funny.

Discussing Two Sought Adventure I mentioned how these two are such fun and unique S&S characters because, in a lot of ways, they know that they’re S&S characters – both of them envision themselves as daring swashbucklers with steely nerves and unmatched skill, true heroes of their Age. They are, literally and consciously, adventurers, and this fully informs the view of both themselves and the world around them. Because of that, their motivation is never in doubt or has to be hand-waved away – Fafhrd and The Gray Mouser will always behave “heroically” in their stories, because they are (and they KNOW they are) the “heroes.” Of course, they’re also very well-developed characters, with Leiber writing with very clearly defined characters in mind.

Mechanically, their interactions are also interesting – so many great S&S stories are centered around hard-bitten lone wolf types, which by necessity means that there tends not to be too much interiority on display with the main characters – Conan is almost always an enigma, really, and we as readers rarely get to see WHY and HOW he’s deciding on what he wants to do. That limitation is why the best Conan stories all have a secondary character that interacts with Conan, questions him, gets him to explain himself and his plans, etc. With Leiber, there’s no need for that – he’s given us two characters that are intimately bound together, and who are always very consciously playing a part for both themselves and one another. Leiber, son of actors and an actor himself (as well as someone very interested literarily in Elizabethean dramas) has made a very conscious, very deliberate decision in the way he portrays these two, and it lets him generate these interesting and fun bits of dialog and scenarios, like we’re seeing here.

The Mouser, always (and often hilariously) the more hot-headed of the two of them, cools himself sufficiently to agree that they should at least be PREPARED to meet with some resistance in attacking the Thieves’ Guildhall directly. This is wise, because they are immediately confronted with sneaky ambushes! Each of them neutralizes the other’s threats in kind, which is another neat little benefit of having two equal participants in the adventure as your protagonists. Then, menaced from the street, the pair are forced to head deeper into the Guild’s inner chambers where, strangely, they meet no further resistance; it’s almost like something has happened, and these two are just stumbling into it. But what else can they do? They make there way to Krovas’s rooms, hoping to find Fissif and the stolen skull there.

The red-haired woman flees through a secret door, taking the skull and locking the passage behind her. Frustrated in their pursuit, our two heroes are busy contemplating the barred passage behind thick curtains when, suddenly, Fafhrd remembers Krovas, who they left, oddly motionless and oddly complexioned, at the desk in the room. They approach him slowly and with needless caution for, of course, he’s dead, mysteriously strangled to death. This puts it a crimp in the Mouser’s half-formed plan of holding Krovas hostage in order to escape, something of immediate concern because now they hear voices approaching! They sneak behind the curtains just as a bunch of cutthroats arrive, including the betrayer Fissif and another thief they recognize as Slevyas, the #2 in the Guild. But something is going down – the thieves are all nervous and seemingly scared, and Fissif is in deep shit with Slevyas, who demands to know where the Jeweled Skull is.

Slevyas orders a Thief’s Trial of Fissif, whom he obviously believes has betrayed the Guild and connived with Fafhrd and The Mouser to steal the skull for themselves. It’s a fun bit of formal procedure that really hammers home the bureaucratic nature of the Thieves’ Guild. We get a nice little scene summarizing the mission, including some fun bits where our heroes get to hear themselves talked about graciously, and Fissif gets to reiterate what happened – the fuckin’ skull killed Krovas! Judgment is postponed, however, when a thief runs in to let Sleyvas know that the watchers on the roof haven’t seen ANYBODY leave…which means Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are STILL in the building!

I mean, what a great image, huh? The drapes billowing out, the onrushing Mouser and Fafhrd leaping into action, it’s very dramatic! But of course, you don’t get to be a Master Thief without learning a few tricks; Sleyvas is nimble as a cat, and he ducks and dodges and avoids Fafrhd’s murderous blow. The whole room is in chaos, but Fissif throws a knife at Fafrhd, bonking him on the head with the pommel and muddling the poor barbarian mightily as he and the Mouser dart out the door and into the labyrinthine interior of the Guild Hall.

The Mouser knows the layout, so he leads them in their flight, pursuit hot on their heels. Fafhrd’s head is just starting to clear when he bonks it again against a low doorframe – he’s having a rough night. Fuddled again with a severe head injury, he stumbles one way, leaving the Mouser behind to face an assailant on his own (which he handily dispatches). But the rest of the thieves are hot on his heels, and he splits, heading in a different direction than Fafhrd.

We cut to poor Fafhrd, stumbling around with a concussion – he’s been sick and is having trouble ordering events, and he feels at least three lumps on his head as he bumbles his way through what must be a disused and forgotten deep cellar in the Thieves’ HQ. At some point he stumbles of a secret passage. Everything is dusty and strangely hot, and he’s got no light, instead crawling around blindly, prey to the sorts of weird illusions you get if you’ve ever spent anytime in pure lightless dark. He seems to catch a strange, sepulchral scent, a sort of tomb-ish spiciness, and there are strange whirring things in the air and around his head, bats presumably. It’s very spooky and claustrophobic and unearthly.

Bone bats! That’s great, isn’t it?

Fafhrd then catches another sound, and when he shouts he hears from the echoes that he has come upon a very large chamber of some sort. And he’s not alone!

Great, weird scene, with Fafhrd in the dark, unable to see anything, and yet obviously able to be seen by whatever is in the tomb with him. Already we the readers have a sense of what these things are, of course: the spicy, dry, hot air has primed us for tombs or crypts, and the undead skeletal bats flitting around have got us in a very necromantic frame of mind too, so there’s little surprise that these sepulchral voices are the undead liches of long dead Master Thieves, compatriots of the late Ohmphal. Long ago they demanded the return of the lost skull, and their dark sorcery informs them that Fafhrd was one of the three who HAD finally done as they wished…though of course, he hasn’t brought the skull back with him. And that’s a problem:

Justifiably spooked, Fafhrd flees wildly off into the dark, charged (on pain of horrible death) with returning the skull by next midnight! And then, having escaped the secret tomb and finally making his way back to the dusty cellars, Fafhrd gets one more traumatic brain injury when he gets bonked on the head by Fissif, who was skulking around down there. Fafhrd is brought before Sleyvas and, seeing as how he doesn’t have the skull, the Thieves decide that that means the Mouser MUST have it…so they make some plans and send a message to the Mouser, who is waiting in vain for his friend back at their favorite bar, the Silver Eel:

The bar scene is a fun one – Leiber is interested in all the little background stuff happening in his fantasy city, really just as much as the main action, and so every scene is populated by these fun little vignettes that do so much to enrich the world he’s created. The drunken soldiers, the barkeep, the squalid surroundings, it’s a lot of fun. And then, of course, when we have to get back to the Real Action, Leiber doesn’t dissapoint; the line “we will begin to kill the Northerner” is really great, a grim and brutal threat of torture and eventual death. It’s fun!

Of course, the Mouser is in a bit of a bind here, what with not actually having the Skull of Ohmphal. But, being the Mouser, he’s got a very cunning plan.

We smash cut back to the misty, murky streets of Lankhmar, where a little old lady is making her way slowly and carefully towards the house where a certain red-haired woman lives. There’re, again, more great scenes of the city and the people in it, and some fun interactions between them as this frail old woman picking her way through the dark. Finally, the old woman reaches her destination:

Thus does the Mouser, disguised as a mysterious and witchy old woman, gains entrance to the fortress-like House of Ivlis!

The whole scene between the Mouser and Ivlis is really fun, as our hero tries to bluff his way into her confidence and trick her into betraying the location of the Skull. He also notices the signs of a secret door at the back of the room, presumably one that connects with the Thieves’ Guild next door, a very handy thing for him what with midnight coming on. It’s always fun when the Mouser goes into full on theatrical mode, and Leiber is having fun here, making his character revel in every lie and trick as he wrangles what he needs out of the besieged Ivlis. Equally fun is when the Mouser overplays his hand, which happens when he screams out about smelling the bones of a dead man; Ivlis glances up at an unlit lamp on the wall, but the Mouser’s triumphant look betrays him. There’s a brief, silent struggle, but the Mouser succeeds in overpowering and tying up Ivlis, and claiming the Skull from it’s hiding place!

Smash cut back to the Thieves Guide, where a water clock is dripping its way to midnight; Fafhrd, tied up in a chair, is surrounded by grim thieves who, when midnight comes round, will begin to kill him slowly and painfully. But while they’re waiting, Sleyvas is browbeating his underlings, one of whom got perilously close to the horrible tombs below the guildhall.

The strange events, the uncanny halls beneath the guild that none knew about, the strange marks on the late Krovas’s neck…all of these things are beginning to spook the thieves a bit. And, like a good skald, Fafhrd seizes on the moment to both perform some Northern Tale-Telling AND buy himself some time:

Fun stuff – Sword & Sorcery is sometimes accused of being overly reliant on physicality and violence, and while Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser certainly slaughter their fair share of mooks, you can ALSO see the way Leiber highlights their wits and, in particular, their ability to perform as part of their heroic repertoire. The Mouser’s disguise as a Wise Woman, and now Fafhrd’s skaldic recitation of his adventure in the crypt are just as much moments of heroism and derring-do as any fight or scramble up a cliff, for instance, and Leiber (who again was himself an actor) revels in them. It’s a real fun part of these stories, both a part of their charm AS WELL AS a key to understanding their importance to the development of the genre.

Anyway, Fafhrd has totally captured the attention of his audience with his grim tale of undead horror deep beneath this very guildhall! The water clock has long since run out, and yet they have let him continue talking, and they don’t even notice the slight skritching and scratching coming from the wall behind the curtains.

ANOTHER performance, this time from The Mouser who, having snuck back into the hall via the secret passage in Ivlis’s room, is now pretending to be the ghost of Ohmphal come to pronounce judgement on them all! It’s really fun, particularly in the way the Mouser/Ohmphal engineers Fafhrd’s release, which has all the hallmarks of a hasty improvisation:

I mean, c’mon, that’s fun! And, spooked all to hell as they are, the thieves comply, cutting Fafhrd’s bonds and sending him forward. But, before he can reach the safety of the curtain, there’s an animal scream of rage from the curtains, which begin billowing and flapping, as if some great struggle were happening. Ivlis has broken her bonds and followed the Mouser down the hall, and now she (and her guards) have attacked him!

And then all hell breaks loose! The thieves attack, the bodyguards attack, Ivlis attacks, our Heroes attack, everybody is whomping on everybody, though shortly Ivlis (and her last remaining guard) side with Fafhrd and the Mouser when they see that they are being attacked by Sleyvas and the thieves. There’s dead and wounded everywhere, but the thieves are more numerous and things look grim for our heroes when, suddenly:

But Slevyas is a staunch materialist, right to the end:

But no one does follow Slevyas, and he alone charges in, meeting Fafhrd and the Mouser in battle. A furious combat ensues, though one curiously quiet and lonely – for the rest of the thieves have shrunk back against the wall in silent fear!

A grim doom has descended on the thieves!

And then, we reach the end of the story:

And that’s the end of Fritz Leiber’s “Thieves’ House,” from 1943.

It’s a blast; Leiber is such a fun writer, and he’s got a very strong hand on the tiller in these stories, writing them exactly the way he wants and producing exactly the sort of effect he’s looking for, I think. Now, some people I’ve spoken to find Leiber, and his S&S stories in particular, a little too self-aware for their tastes, and that’s fine – the heart wants what it wants, after all. But you can’t deny that Leiber succeeds in doing exactly what he wants to do with these stories, even if they’re not to your particular taste.

Of course, I think that while it’s true that Leiber was certainly aware of the genre he was writing in (even if it didn’t have a name yet) and was, in fact, often commenting on it, he’s also sincerely writing excellent adventure stories about two very interesting characters. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser are spectacular fantasy protagonists, rough and ready but also very much interested in having a good time and cultivating a myth about themselves while they do it. In fact, so much of the fun in these stories comes from the way both characters are constantly trying to reassure themselves and each other that they are truly real life heroic adventurers in a world of sorcery and peril. There’s an existential quality to these two that’s fairly rare in the world of fantasy fiction – they are constantly evaluating themselves, interrogating their place in their world in relation to this Ideal Adventurer. Often, the comedy in the series comes from them twisting themselves in knots as they try to JUSTIFY their less-than-heroic actions within this same S&S hero framework. They’re just a lot of fun, and it’s something that I think the genre would benefit from if more writers today tried to emulate Leiber’s approach.

I mentioned above that this story also seems to be the first to introduce the idea of a thieves’ guild into the genre. This is a pretty big deal, one of those huge gravitational sort of pulls that end up dominating the genre, to the point that they’re kind of invisible and taken for granted. The idea that there is a craft guild of criminals operating within a fantasy city is a huge part of the genre’s landscape, providing a lot of narrative potential energy as well as giving writers the chance to engine in some light mafia-style highjinks if they want to. With respect to fantasy TTRPG’s this story, like so much of Leiber’s fantasy, is absolutely foundational – imagine D&D or WFRP without Thieves’ Guilds; it can’t be done!

Now, I don’t know where exactly ol’ Fritz got the idea for his Thieves’ Guild; as far I know no one has every found a letter or notes or anything where he explained its origin. In some ways, it might just be a natural outgrowth of his obviously somewhat skewed and satirical approach to Lankhmar – the idea of a guild of criminals is a funny, weird idea, and it fits perfectly in with the other absurdities he’d go on to invent for his secondary world of Nehwon.

HOWEVER, to me, I can’t help but see the shadow of Cervantes here, particularly from his short story Riconete y Cortadillo which is about two extremely self-important and self-aggrandizing thieves who meet on the road, become fast friends and devoted comrades, and then are inducted into an extremely ridiculous and comedically bureaucratic Thieves’ Guild in the great port city of Seville. In particular, it’s interesting to me how, in Leiber’s story, the Guild starts out atheistic and materialistic, only to end up deeply religious and cultish about their Dead Masters deep in the Tombs beneath the Guildhall; in Cervantes’ story, the Guild is rife with superstitions and complex rituals, like all good secret societies. That Leiber would’ve been familiar with the story seems extremely likely; after all, he was a devoted lover of that era’s literature, and if you’re going to read any 17th century Spanish lit in translation, you’ll certainly be familiar with THE MOST FAMOUS WRITER OF THAT PLACE AND TIME. I know that Fafhrd and the Mouser were modeled on Leiber and his pal (and cocreator of Lankhmar) Harry Fischer, but I think there’s a lot of Rincon and Cortado in the two, particularly in their ridiculous grandiloquence and self-conceit, as well as in their deep loyalty to one another. Anyway, it’s interesting, and if true it puts Cervantes in the lineage of Sword & Sorcery’s deep ancestors, which I really like.

But, regardless, I think this is a very fun story, and it’s importance in the history of the genre can’t be denied. A good way to start of the Yule Season’s S&S, I think!