Trying to do these little free writing essay/dissections a bit more frequently because a) it is Hallowe’en season, after all, and b) it seems like we’re in another round of “social media death throes.” This time it’s over on Bluesky where the CEO appears to be following the Elon Musk playbook of going insane to protect the rights of fascists and TERF scum. It’s not like anyone reads blogs either (I know, I’ve got the stats for this little project right here), but we shan’t let that discourage us! So, with our hearts blazing and our eyes open, let us once again enter the mysterious, pathless wilderness that is the Pulps! And for today we have a fun (and interesting!) story: Robert Barbour Johnson’s homage to Lovecraft, “Far Below” from the 1939 June-July megaissue of Weird Tales!

Ol’ Bob Barbour Johnson seems to have been a bit of an odd duck. While a fairly prolific writer, particularly of circus tales later in life, his footprint in Weird Tales is small but deep, if that makes sense; I mean he didn’t actually write a lot for the magazine, publishing I think only six stories between ’35 – ’41, with a couple more weird stories published in other magazines later. But, despite that, readers apparently thought fairly highly of his writing, particularly of today’s story, “Far Below.” Depending on where you’re getting your info, it was either voted by the readers as the single best story published in Weird Tales OR editor Dorothy McIllwraith said it was the best story the magazine ever published.

Both statements are incorrect, although this is a good and fairly interesting story. But that kind of odd indeterminacy around Johnson seems to be fairly typical. For instance, he’s clearly a fan of Lovecraft (as we’ll see when we dive into the story today) but, with great grandiosity, Johnson says that Lovecraft wrote HIM a fan letter after reading Johnson’s 1935 story “Lead Soldiers.” It’s possible that this is true; Lovecraft was both a voluminous letter writer and the sort of person who would certainly praise work he thought good and interesting…but it just doesn’t feel correct, particularly because the story this “fan letter” is supposedly about doesn’t seem like the sort of thing Lovecraft would’ve liked! “Lead Soldiers” is about a tinpot fascist dictator whose delusions of grandeur are leading the world towards another World War, but he ends up getting killed by a bunch of toy soldiers. It’s VERY timely (then and now, sadly), EXTREMELY didactic, and BLUDGEONINGLY allegorical – not really the sort of work Lovecraft generally praised! It seems like this claim of a fan letter from Lovecraft comes out of some memoir/reminiscences type essays Johnson wrote later in life, and while I haven’t chased them down to read them in full, I gather that there’s a general Derlethian tone to them with respect to Johnson’s view of himself.

(As an aside, it appears there was a Joshi-edited-and-introduced collection of Johnson’s work that, in addition to the weird fiction, also included a few of these biographical essays. It was titled Far Below and Other Weird Stories and was published in 2021 by Weird House Press, though it’s out of print and seems like it must’ve been an extremely small run, since I can’t find a copy for sale anywhere. If you know about it or have one, hit me up!)

What is certainly true, however, is that Johnson thought a great deal of Lovecraft, and the story we’re going to be looking at today is, basically, an homage to the Old Gent and a spiritual sequel to his (great) story “Pickman’s Model,” as well as maybe the earliest example of the metafictional appearance of Lovecraft as a Lovecraftian character! But, before we can get to all that, let’s check out the cover and ToC of this big ass issue of Weird Tales!

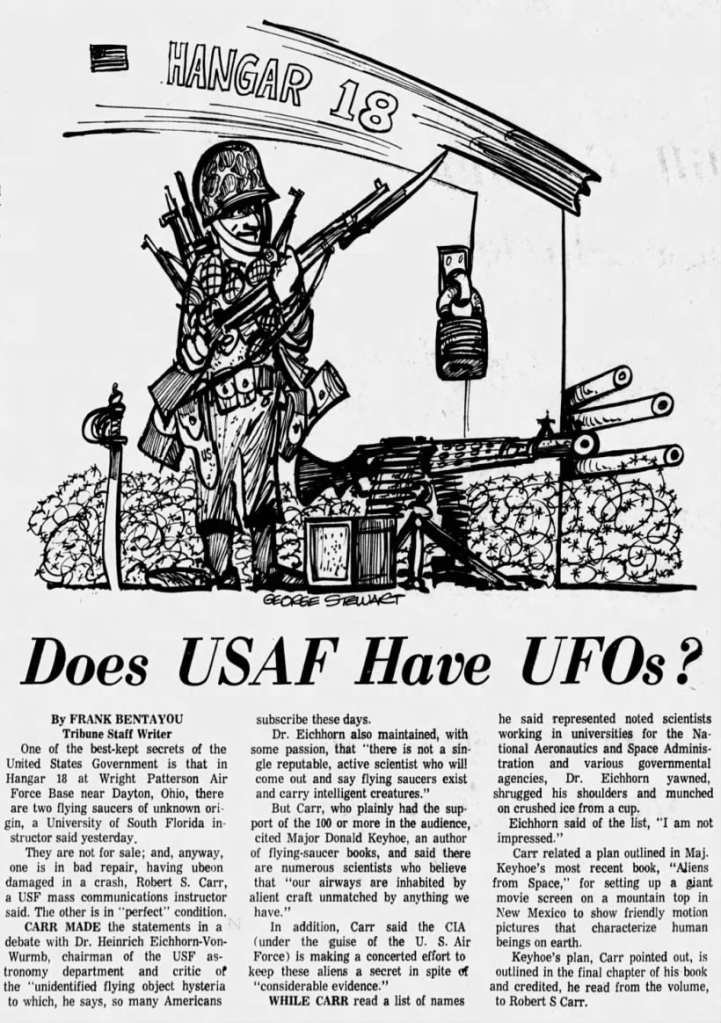

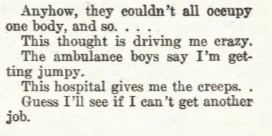

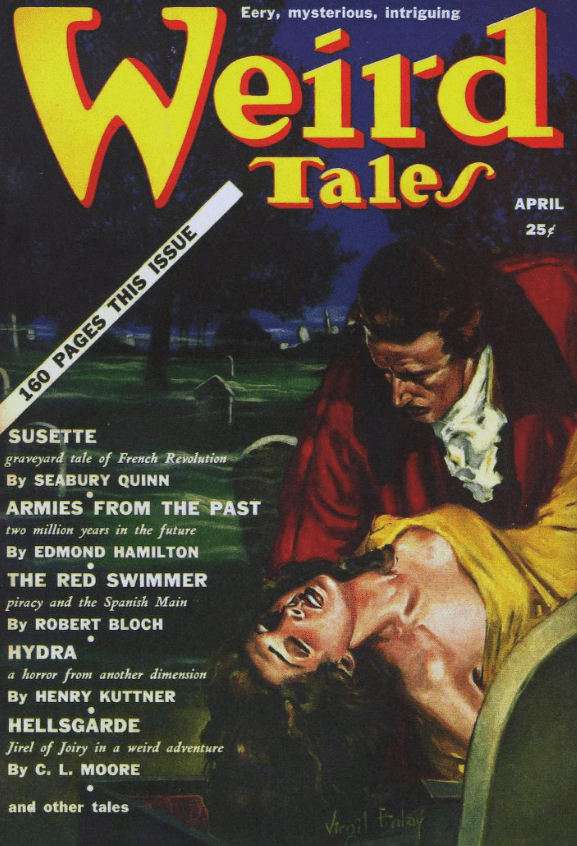

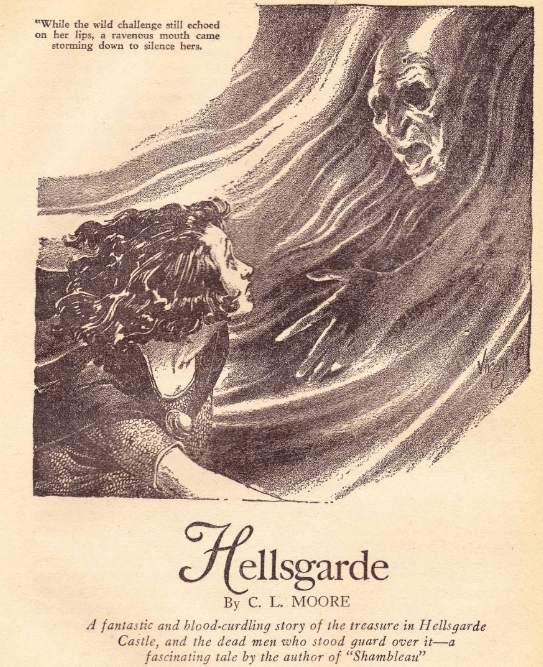

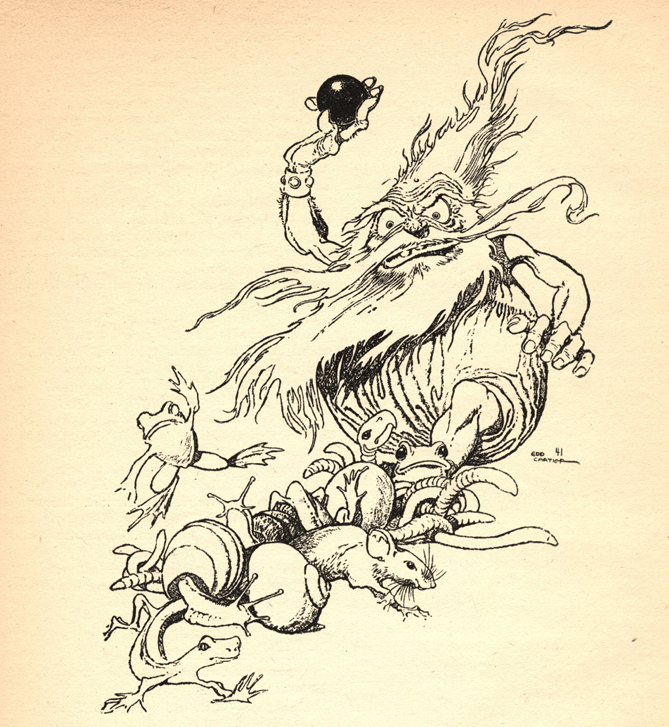

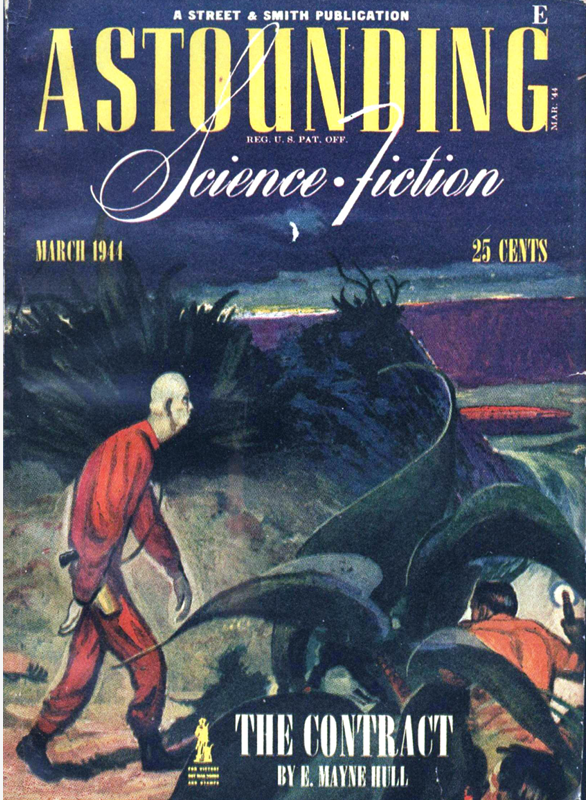

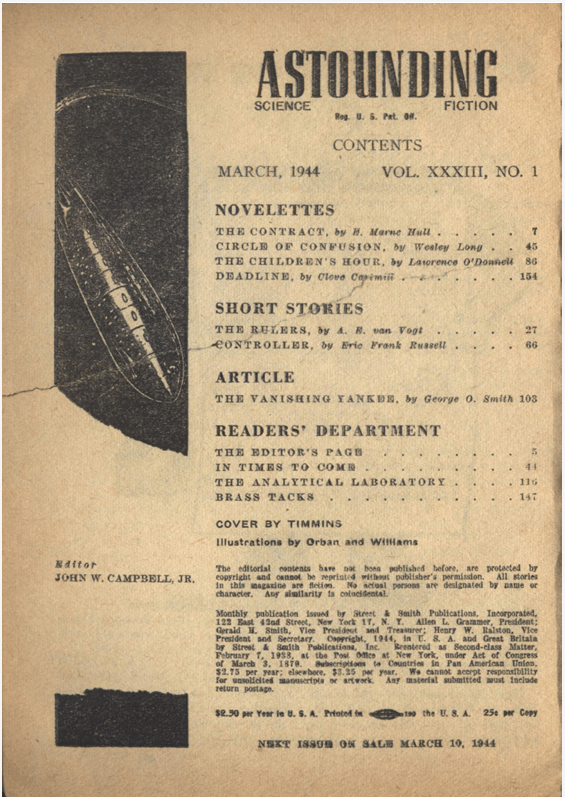

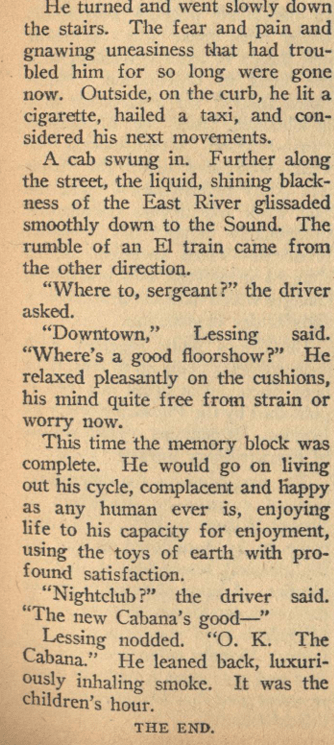

An incredible cover by the inimitable Virgil Finlay, representing a cavalier of some sort exploring a mysterious and ghoul-ridden cavern. Absolute perfection, just a blast all around. No idea what story it’s supposed to be illustrative of, and it’s entirely possible Finlay only had the broadest of scenic outlines provided to him. But who cares! Let Finlay paint up whatever weird shit he wants, he’s one of the best to ever have graced the covers of the pulps with his talents!

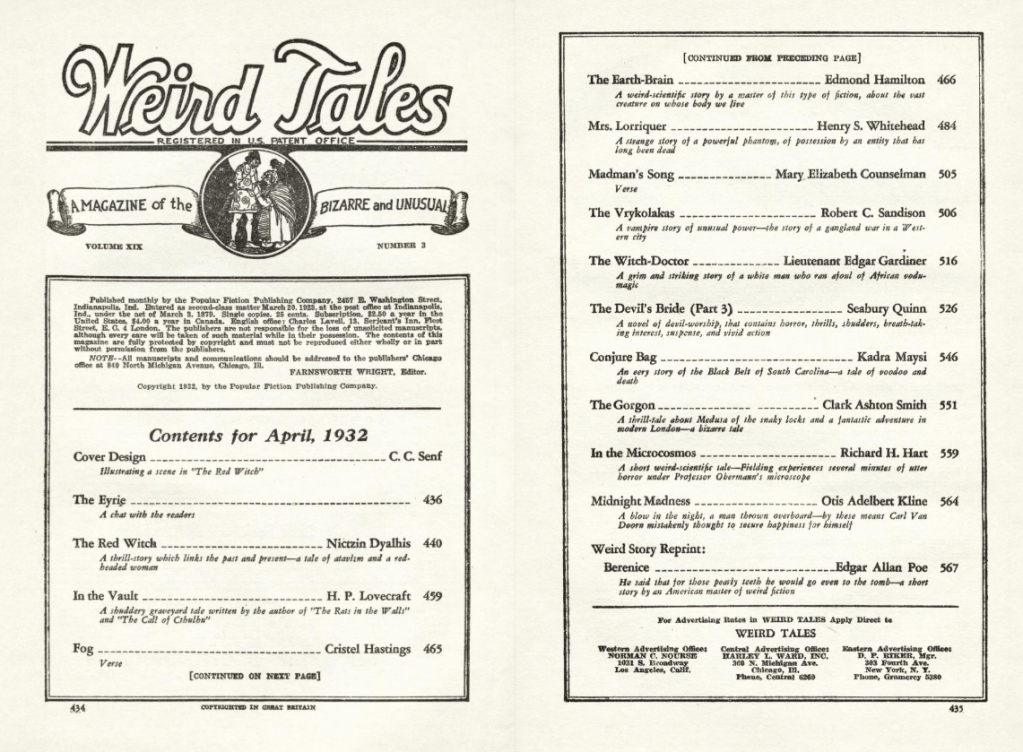

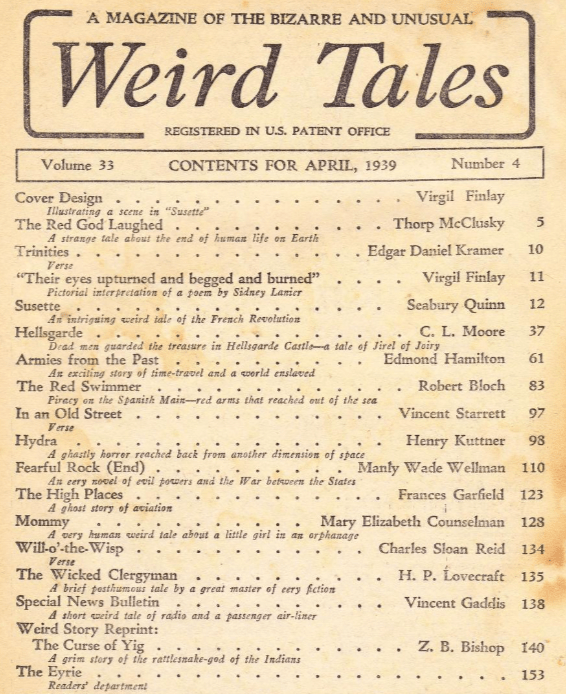

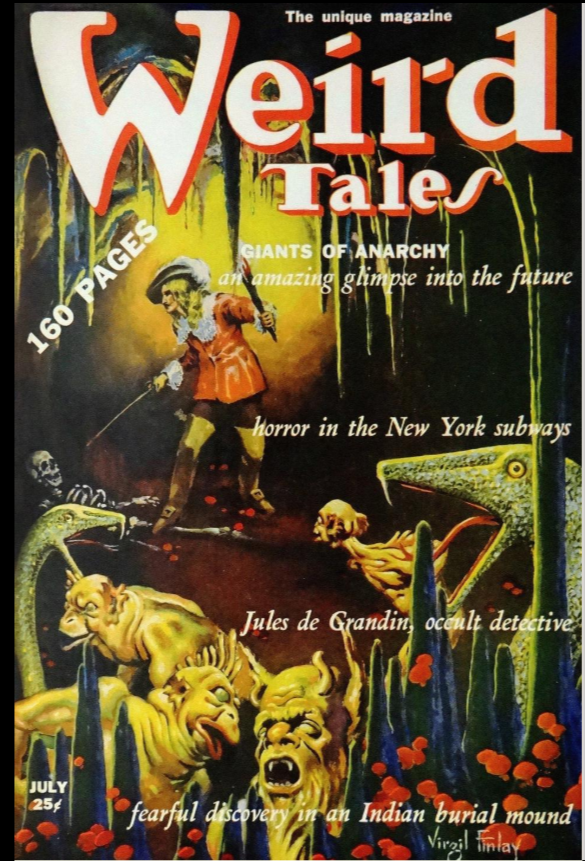

ToC-wise, it’s a heavy-hitter, lots of Lovecraft and Howard on here, some CAS. We’re VERY late in the Farnsworth Wright run here, and the magazine is facing some challenges, but you can see they’re still putting up the good fight here, and there’s some fun weirdness in this big ol’ issue. Also, it’s always worthy pointing out the magazine’s commitment to poetry – it’s such a huge part of weird fiction’s history and lineage, and it’s nice that the premier magazine (that, I would argue, actually created the genre by doing the necessary boundary definition work) both recognized and encouraged poetical weirdness within its pages!

Now, on to the story!

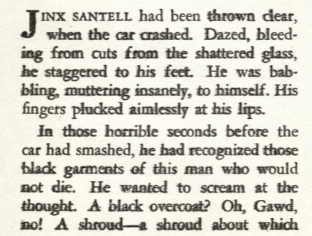

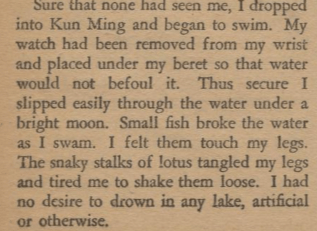

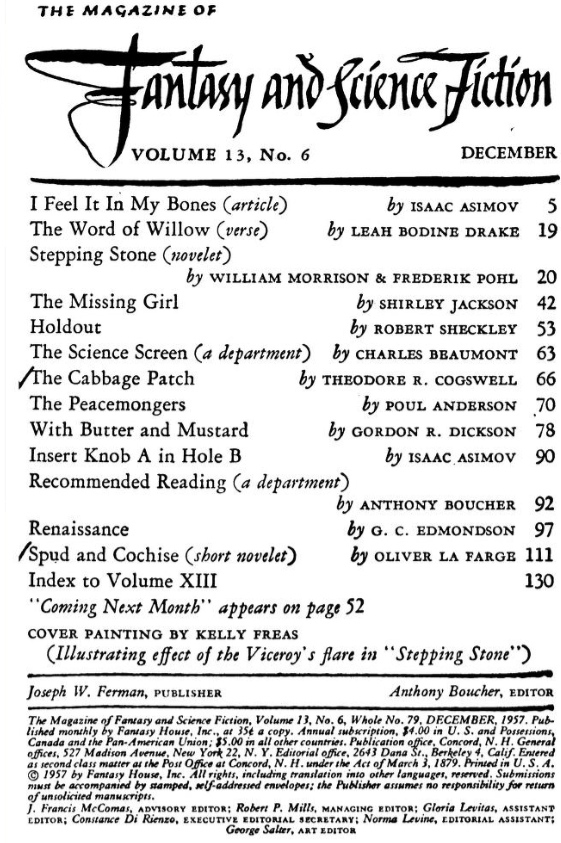

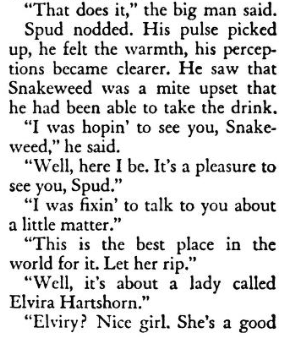

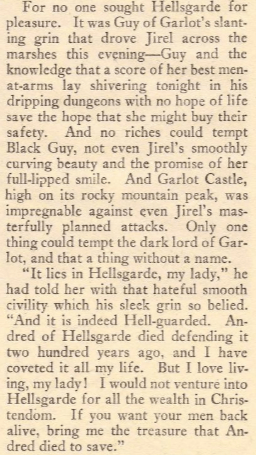

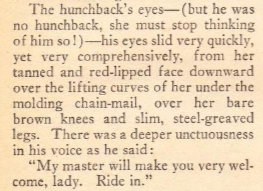

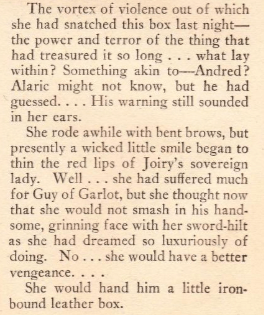

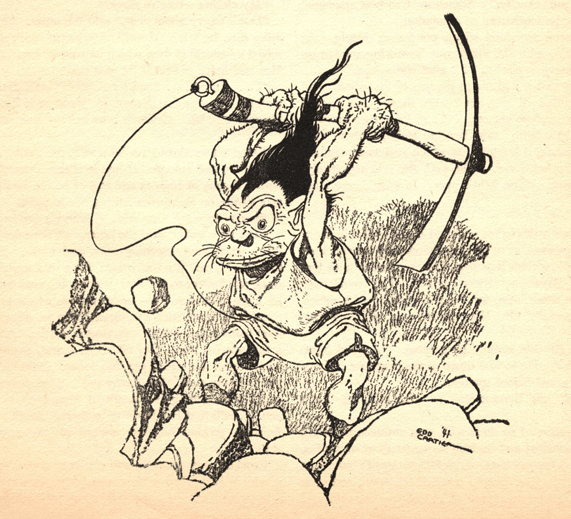

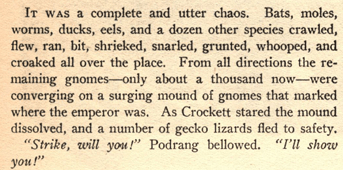

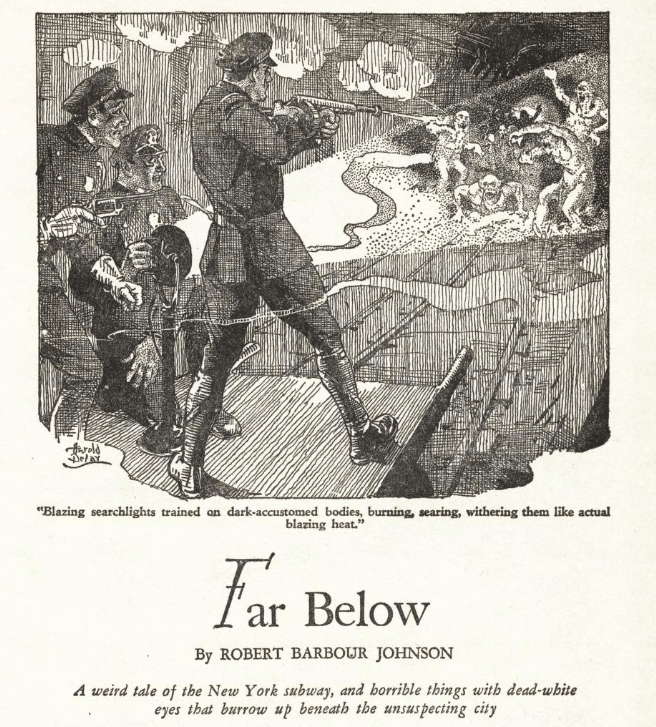

Absolutely incredible art from the great Harold DeLay here – those old school NYPD uniforms, on a weird little rail cart, emptying a machine gun into a horde of hellish C.H.U.D.s…truly a classic! Excellent little atmospheric touches here too; the smoke, the beam of light, the expressions, and the way the horrible ghoulish horde recedes into the background of the tunnel. Just incredible, action-packed stuff, immediately eye-catching and exactly the sort of thing that gets people to actually sit down and read the story! DeLay was a great artist, and it shows. He did some excellent Conan illustrations for Weird Tales, including some for “Red Nails,” and would go on to a career in comics, something he’s obviously well suited for, given the compact and propulsive nature of his artwork.

The little italicized summary under the title is evocative and tells you everything you know, nice and succinct without giving anything away from the story. That, and the spoiler-free art, is a nice surprise!

A great, powerful start to the story; the reader is immediately drawn into whatever the hell is happening, and the quick transition from the “roar and the howl” into the revelation that the “thing” is a subway train is really nicely executed. Johnson is a good writer, and there’s some real craft in this story!

It is also, of course, a story of its time, which is why the next part has some eye-rolling White Nonsense™ in it:

Johnson wants to highlight the big, heterogeneous nature of New York with a tableau of society, specifically calling out the presence of the minorities in the subway car to give us a kind of population sample that is (unknowingly) under threat in this story. It’s cringe-worthy language, of course, and the description of the two black people as “grinning” is particularly unpleasant, an image straight out of minstrel show. It’s something you have to confront in these older stories, but I think a modern reader, acknowledging the racism, can then focus on the narrative function of the scene like we just discussed: the way Johnson is giving us a thumbnail sketch of the civilian population of NYC, dull businessmen, smoochin’ folks, and a substantial proportion of non-WASPs. Very urban and very modern subway commuters!

The medias res beginning opens up and we realize we’re in some kind of little room, where our narrator is hanging out with someone who, apparently, knows the subway system in detail. We learn that the room is actually some kind of command center, with state-of-the-art ultra-modern technology that lets them monitor the passage of the subway cars:

The Mayor Walker here is a real person, good ol’ Jimmy Walker, the mayor of New York City from 1926 to his resignation in disgrace (and at the behest of FDR) in ’36. He had been a Tammany Hall boy, and become a sort of poster child for bribery and corruption at the time; Weird Tales readers, even those not from NYC, would absolutely have recognized the name, as well as the context of his getting this super expensive and super complex monitoring system installed in the subway as he was resigning. It’s an interesting historical, but it functions in the story to really GROUND us in a very specific time and place – this is no Lovecraft country invented landscape, or even a quasi-mythic NYC. This is New York City, 1939, exactly as you know it; it’s an important part of the power of the story, this very precise, very real grounding.

It also offers a convenient date for the Subway Expert to use to explode the ridiculous conception of just how long whatever it is they’re talking about has been going on:

So we get a sense that there’s something old and frightful going on, and that there’s a concerted, directed conspiracy to keep it under wraps because the truth is so terrible, so horrible, that it would destroy civilization (or at least NYC) to know what was happening. The evocation of Chateau-Thierry and Verdun, famously bloody battlefields in WWI, is interesting; this story is a sequel of sorts to Lovecraft’s own “Pickman’s Model,” and in it the narrator mentions how he’d seen some rough stuff in France, but even that hadn’t been enough to prepare him for the horror he encountered (in the story). Here’s Johnson making sure to hit that exact same point – the horrors of modern, mechanized warfare are nothing to the horror down in these tunnels, AND it’s something with a long, deep history.

An interesting meditation from the Subway Expert on what it means to be in contact with Horror, day in and day out, and the ways the mind shifts and adapts to survive.

The story shifts into a multiple-page long monolog from the Subway Expert, another stylistic choice in imitation (or homage) of Lovecraft’s “Pickman’s Model,” which is entirely told as the first person dialog of a character. It’s a very effective narrative trick because in addition to letting the writer give a LOT of exposition very naturally, it also anchors the reader in the very personal, very visceral experiences of the view point character, something that can only help a horror story.

We learn that the Horrible Things that our Subway Expert has been tasked with fighting are seemingly restricted to a very small segment of the subway system, for reasons unknown. This is lucky, because its evident that successful containment of this threat is costly and complicated – there’re a bunch of militarized police stationed down here, with multiple command-and-control centers spaced along the line, and lots of careful, attentive monitoring for signs of “Them!” And it takes it’s toll on these members of the NYPD’s “Special Detail:”

Grim stuff indeed, both from the perspective of people in danger of being transformed by the work of combatting these horrors, as well as from the obvious extrajudiciality of the whole apparatus! We learn that these subway-patrollin’ Special Detail Boys are paid handsomely for their work, and that why they are *technically* part of the NYPD, and wear the uniform, they are outside of the hierarchy, free from usual discipline, and apparently answerable only to themselves. Wild, fascist shit! We also get a little bit more about out interlocuter here:

So our guy used to be a Professor who worked at the AMNH, a specialist in gorillas. He mentions that he’d been on Carl Akeley’s first African expedition when he was recruited for this subway hell job. Incidentally, although the “Akeley” name would seem to be another example of Lovecraftian hat-tipping (Henry Akeley was the rural hermit menaced by the Mi-Go in “The Whisperer in Darkness”), Carl Akeley was a real guy, a hugely important figure in museum display technology and taxidermy, perfecting and advocating a method of “life-like” presentation of specimens for museums; the Hall of African Mammals at the AMNH is named after him. Akeley’s first professional visit to Africa was in 1896, but since the NYC subway didn’t open until 1904, I reckon Craig here is referring to Akeley’s first expedition for the AMNH, which would be around 1921 or so. Incidentally, that trip was a turning point for Akeley, who had undertaken it as part of an attempt to learn more about LIVING gorillas and determine whether it was “okay” to kill and stuff them for museums back home – he came to the conclusion that it was not, and was instrumental in starting one of the first Gorilla preserves in Africa.

ANYWAY our guy Craig gets recruited by Delta Green the NYPD Special Detail because he’s an expert in comparative anatomy. He dissects a specimen of the Things (losing 1d10 SAN, presumably), and submits a report detailing the mad truth of the thing:

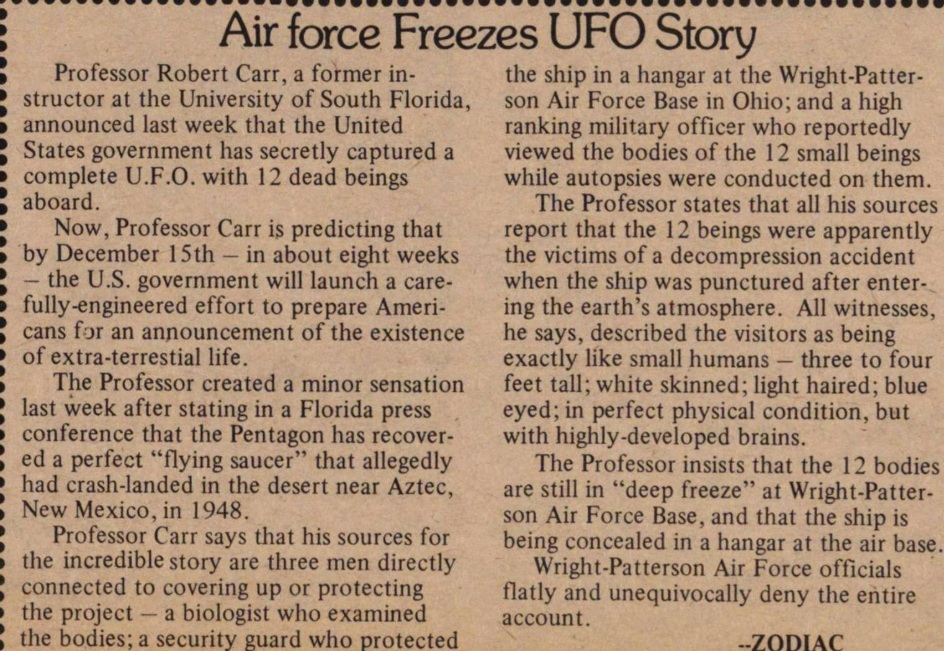

It turns out that much of what he’d discovered was already known, or at least suspected, by the shadowy cabal of the NYC Transit Authority or whoever it is; they had extensive reports about the subway accident, showing that it was a deliberate, planned attack by horrible anthropophagus mole-men…which sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

That’s from Lovecraft’s “Pickman’s Model” from 1927, and yeah, sure, it’s a subway PLATFORM in Boston, but it’s very clearly the inspiring image for this story!

The “accident” as described by Craig is pretty gruesome – men, women, children, all getting munched on in the dark. It’s some grisly shit! Seems like something that’d be difficult to cover up, doesn’t it?

More brutal authoritarian actions by the Special Detail of the NYPD! It’s wild stuff!

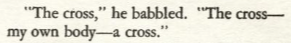

Craig goes into the history of their anti-ghoul actions, and how hard the work was at first, before all the modern technology and approaches had been figured out. There’s some great, spooky writing in this section; Craig remembrances of hunting the Things through the dark tunnels, of glinting eyes in the dark, half-seen white forms flitting into the shadows, tittering mirthless laughter…it’s phenomenal, really atmospheric and legitimately unsettling.

Then we get a long section about the historical and geographical distribution of the ghouls – they’ve been here for a long time, there’s evidence that the Indians knew about them and had taken steps to nullify their danger, and there’s even a kind of funny (if tasteless) retconning of the reason for the cheap price the Dutch got for Manhattan. It’s honestly some very good Lovecraftian history, suggestive fictions woven through history and folklore and things like references to darker meanings behind certain passages in the real book “History of the City of New York” by Mary Booth; it’s not easy to do, and you’ll often run across clumsy attempts in the pastiches of Lovecraft, but here it’s pretty adroitly handled, I’d say! And then we get to a real fun bit:

I mean, c’mon – that’s just good plain fun, isn’t it? Lovecraft, presumably while living in the city, took Craig’s Grand Tour of NYC’s Subway from Hell, and much like Pickman’s practice of painting from life, those experiences are what gave Lovecraft’s story a certain hellish “authenticity.” A delightful bit of metafiction, I think!

Craig goes into the details of their work a bit; the Things seem restricted to a certain stretch of the subway, perhaps for some underlying geological reason, he muses. They also seem to restrict their activity to night-time, even though it’s always dark under the earth, which seems to make the NYPD’s Special Detail’s job a whole lot easier, at least. Craig even seems to let slip a hint of bloodlust here:

“We run them down howling with terror” is a bit grim, isn’t it, and then of course there’s Craig admission that they sometimes CAPTURE the things, imprisoning them in some kind of insane Hell Zoo. These specimens are used to illustrate the seriousness of the horrors and the need for a ruthless extrajudicial police force to recalcitrate officials, but of course they are stored in Craig’s laboratory…what’s he doin’ in there, you have to wonder. There’s a very unpleasant suggestion of experimentation, vivisections and such like. And, of course, they can’t keep any individual Thing around for very long – they’re too horrible, too alien, so they end up exterminating them eventually. It’s dark stuff:

Craig’s discourse on the Things is interrupted by a buzzing from The Big Board – there’s activity in the tunnels, movement and sounds picked up by the vast subterranean panopticon that they’ve built up down in the subway tunnel. Our narrator sees something whirr by the window, and Craig proudly explains that it’s a souped-up electric hand cart, chock full o’ cops w/ heavy artillery, dispatched to take care of the Things in the tunnel. Another one is also coming from the opposite direction; they’ll pin the Things between ’em and gun ’em down.

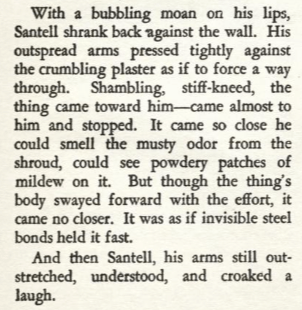

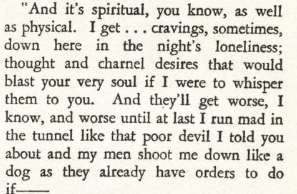

Because there’re microphones all over the tunnels, Craig and the narrator can hear everything that’s happening:

And then we get to the real meat of the story – in a brilliant bit of writing, Johnson has the characters (and us) overhear the action, narrated by Craig, which builds great tension and forces us to confront what, exactly, Craig has become, down here in the dark, hunting monsters:

Just in case you don’t get it, Johnson spells it out in the next section:

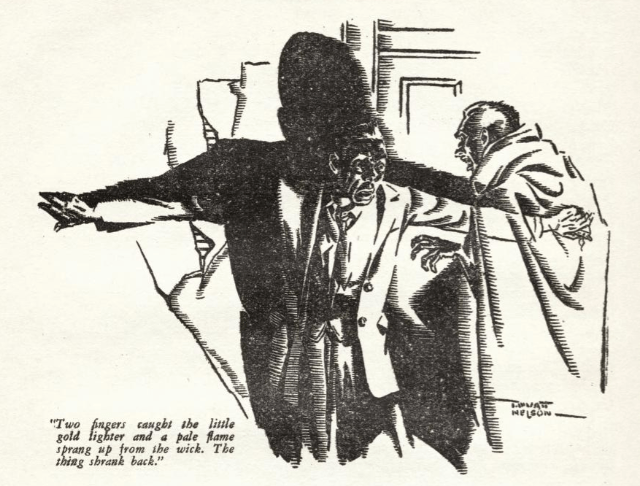

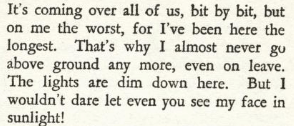

Craig is becoming a ghoul; in fact, all the NYPD Special Detail officers are becoming ghoulish, to a greater or lesser extent, but it’s worse and more pronounced for Craig because he’s been down here the longest. And it’s not just a physical transformation, either!

Even in the midst of his horrible decline, Craig can’t help but be scientifically intrigued by the transformation, however. He muses that perhaps the transformation is the explanation for the origins of the Things, and also why they’ll never be able to exterminate Them fully. He suggests that, while there’s some suggestion of cosmic horror chicanery going on, the transformation is simply atavistic retrogradation, something about being driven underground, being made abject in the dark.

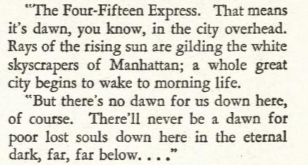

We’re nearing the end of the story; Johnson recapitulates his opening line, the “roar and a howl” bit, as another commuter subway train comes roaring by:

And that’s the end of “Far Below” by Robert Barbour Johnson!

It’s not a long story, and it’s pretty simple structurally, built around a long expository monologue and relying on the neat trick of a character’s second-hand exposure to horror and weirdness. But there’s a lot to unpack, I think!

First off, in our current times (Oct ’25, as of this writing) it’s hard not to read this story as having something to say about both the long history of policing and prisons as well as our very current fascist U.S. government’s use of a militarized, extrajudicial police force to terrorize those it has deemed undesirable. The NYPD Special Detail’s powers are unchecked, their funding unlimited, their remit unrestricted; they are heavily armed, are capable of apparently ignoring any and all oversight, and consider themselves absolutely essential to the continuity of human civilization. And, more importantly, they are completely dehumanized by their task, transforming into literal monsters because of the work they do. It’s pretty on the nose!

Of course, that reading is a little undercut by the fact that, within the text, the Things are ontogenically capital-E Evil, right? They sabotage a subway train and devour the survivors alive, fer chrissake. That complicates the Nietzschean “Beware lest ye become monsters” reading, because these are of course literal monsters; in this way, the horrible degradation Craig and his brave Mole Cops are facing is actually heroically tragic, a sad but necessary sacrifice that must be made for the good of all.

I kind of suspect that, for Johnson, it’s the second one, about brave men sacrificing body and souls, that he wanted us to take away from it. Of course, Johnson was politically-minded; his story “Lead Soldiers,” for all it being a Moral Fable, shows that he was aware of current events and Had Opinions about them, so it is possible that he was thinking about, say, WWI era interment camps or even the crisis in protests and violent police actions post-WWI, and wanted to talk about that. But the way this story is written, and the climax that it’s building to, suggests that he wants us mostly to focus on the horror these cops are facing, and not trying to get us to think about how dehumanizing the Other dehumanizes Us, you know what I mean? That doesn’t mean we have to adhere to that reading, of course; death of the author and all that (literally, in this case; Johnson died in ’87).

As a piece of weird fiction, I think it’s awfully successful. It’s probably in my mind one of the most successful “inspired by Lovecraft” stories I’ve ever written, right up there with Bloch’s “Notebook Found in a Deserted House” or anything by Michael Shea, for example. Obviously based on that little bit of “Pickman’s Model” I excerpted above (which is super evocative, very brief but very striking in the original story), and I think Johnson does it justice, captures the fun and weirdness and horror of a subway being attacked by monsters.

It’s also neat to see Johnson really taking the conspiracy-ball and running with it. Lovecraft creates what is probably the first “widespread gov’t paranormal conspiracy” in his story “The Shadow over Innsmouth” (written in ’31 and published in ’36) – there, the u.s. gov’t comes in (off screen) and raids the town, blows up devil’s reef, sends a submarine against the Deep One’s city, and then sets up concertation camps for the fish-human hybrid survivors. There’s even a mention that the gov’t brings in “liberal activists” and shows them the horrors they’ve imprisoned, which makes the various civil rights organizations shut up about the camps, something echoed in this story by Johnson. It’s a very striking part of Innsmouth, and Johnson does it honor here, establishing a plausible and powerful conspiracy built around directly combatting the mythos menaces out there! Has anybody ever done anything with the story in the Delta Green (a cthulhu ttrpg) setting, I wonder? Craig is even a Call of Cthulhu character, in the way he had an expertise that got him plugged into the darker mythos world (and that he’s going insane and will inevitably die horribly).

Anyway, it’s a fun and interesting story, two things that you can’t always say about work with such clear (and acknowledged) connection to Lovecraft. It’s probably the best thing Johnson ever wrote, at least for Weird Tales, and I think it deserves to be read and remembered for more than just “the sequel to Pickman” that it sometimes seems to be cast as. It’s an inventive story with some good, scary imagery, it uses its source material well, and it’s a fascinating glimpse into the immediate post-HPL world of weird fiction!