CONTENT WARNING: the story we’re talking about today includes sexual assault.

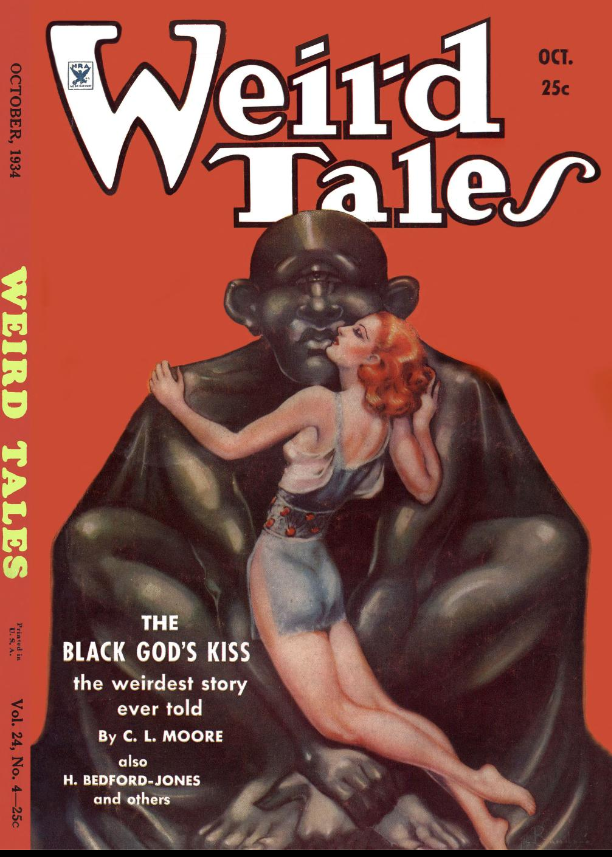

The Yuletide draws nigh, and for me, that means one thing: sword and sorcery! Growing up, for some reason or another, I would often find myself reading fantasy novels around this time of year; Lord of the Rings, The Enchanted Forest Chronicles, Book of the New Sun, big fat books that travelled well for holiday trips and suchlike. But one day I picked up a Fritz Lieber Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser collection, and ever since my xmas time fantasy reading has bent towards the sword-and-sorcery end of the spectrum. That might not be too surprising given that sword-and-sorcery is a subgenre of weird fiction anyway. But it’s decidedly my favorite flavor of fantasy, so it’s a unique pleasure to be able to end Moorevember and begin my annual sword-and-sorcery appreciation month with the very first Jirel of Joiry story from one of the genre’s masters, C.L. Moore! That’s right…it’s “The Black God’s Kiss” from Weird Tales, October 1934.

It’s gonna be wall-to-wall adventuring around here from now through January so we’ll talk the history of sword and sorcery as a genre later, but to lay some groundwork for you: sword and sorcery is the ONE genre that people all definitively agree began in Weird Tales. Specifically, we can point to the publication in December 1932 of the Conan story “The Phoenix and the Sword” as its definitive birthdate. It’s not the first fantasy in the magazine, of course; some of Lovecraft’s dreamlands stories veer dangerously close to the genre, Clark Ashton Smith had already published a number of fantasy-flavored horror stories (including, importantly, “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” in ’31), and REH had even had a couple of “King Kull” stories in the 20s in Weird Tales, but for most people the genre crystalized in ’32 with that Conan story. Mostly that’s because Conan as a character would come to dominate the genre, but I think there’re good literary reasons to pin it there too. A lot of the weird fantasy that had appeared previously was, mostly, very much more in the weird fiction tradition, focusing on horror or mood or lyricism; even Howard’s Kull stories were more mythic than anything else, with very little of the action or adventure we associate with classic S&S. Also, with the Conan story, we get a glimpse at the first really well developed “secondary world” in literature, a pseudo-historical approach to presenting fantastic lands as real political entities with histories and agendas and material concerns, rather than as timeless magical kingdoms. But perhaps most importantly, Howard’s Conan represents the first clear articulation of the central theme of sword and sorcery: a singular human character relying on their strength and cunning in an active struggle with unnatural and dangerously inhuman forces.

The 80s sword and sorcery revival (and backlash), particularly in the movies, has given us a very jaundiced and cynical view of the genre; you say “sword n’sorcery” and what most people envision is a meat-headed barbarian carving his way through a sea of enemies, followed by some gratuitous sex with an uncomfortably exoticized dancing girl. And I mean, sure, that’s a part of it, but in the finest examples of the genre, what you actually have is a story about a person confronting dangers with only themselves (and, in particular, their bodies) to rely on. It’s a literature preoccupied with the ways a person will push their strength, will, and courage to the limits in pursuit of a goal, despite the presence of weird inhuman threats.

That this had an appeal to both readers and writers of weird fiction is understandable, I think…even the most dyed-in-the-wool weird horror fan must eventually confront the fact that, sometimes, you want to see someone punch a gibbering horror right in its non-euclidian face, and that’s precisely the itch Sword and Sorcery scratches. The horrors are real and chilling and soul-shattering in S&S, but not every protagonist has to be a Lovecraftian character that embraces merciful oblivion by fainting at the most narratively convenient moment. And as we know from our very first entry in this year’s Moorevember, that kind of tough, no-nonsense character was something C.L. Moore specialized in writing! So let’s get to it!

Moore got the cover for this story, and it’s one of Brundage’s most famous pieces. The strange, enigmatical expression of the statue is really good, and while Brundage has of course cheesecaked up Jirel of Joiry (giving her longer and more feminine hair and putting her in lingerie), I think the picture actually does a good job at capturing some of the weirdness of Moore’s story. I wonder if there are any interviews or letters from Moore where she says what she thought of the cover?

The ToC this issue is pretty solid, too:

It’s a sword-and-sorcery smorgasbord! Moore, followed immediately by a great Hyperborean story from Clark Ashton Smith (which includes a wizard with an archaeopteryx familiar) AND there’s also the second part (of three) of a pretty great Conan tale (also with some of the raddest evil wizards he ever wrote)! Great fantasy stuff here, plus more straightforward weird fic from Ernst, Wellman, and Julius Long…hell of an issue, honestly!

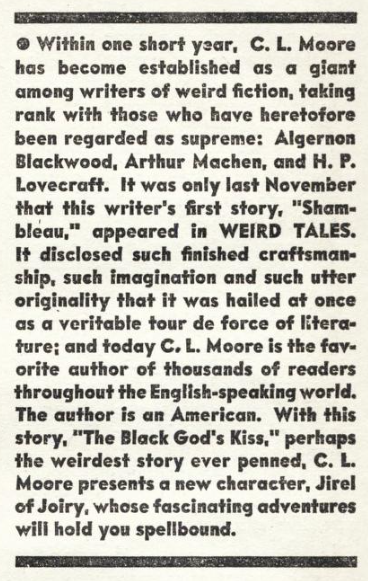

The esteem that Wright and the readers felt for Moore is evident from a nifty (and atypical) little sidebar that was inserted on the first full page of text from the story. Here it is:

Some incredible praise, and puts Moore right in there with truly towering figures of weird literature. It also illustrates just how epochal “Shambleau” was for the magazine and the genre. A real shame that she ever fell off the radar of readers, since she’s absolutely one of the major writers of genre fiction from the early 20th century.

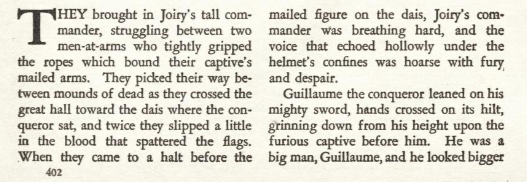

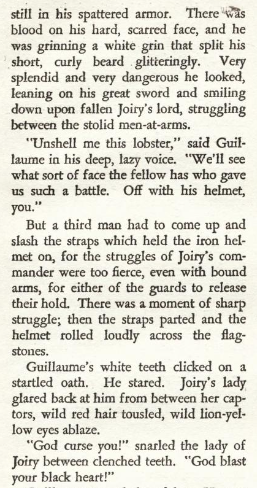

Big giant title illustration that, along with the italicized caption, UNFORTUNELY undercuts the beginning of the story by giving away the fact that Jirel of Joiry is, in fact a woman. It’s a real shame, because Moore clearly begins the story with the idea of surprising the Weird Tales audience with that fact:

Not until the fifth paragraph is Jirel identified as “Joiry’s lady,” after descriptions that paint “Joiry’s tall commander” as martial, physically powerful, and very defiant. It’s a shame that Weird Tales undercuts the reveal with the art and the intro, although hopefully some readers had sped through that and encountered the surprise naturally. It’s a great scene, one of the iconic gender reveals in literature, right up there with Éowyn confronting the Witch-King of Angmar.

Guillaume is, of course, struck by the sudden sight of this warrior woman, one who by his own admission put up a truly valiant fight against him and his men. It’s kind of funny that he besieged Joiry and went through all that without knowing who it was he was facing, isn’t it? Guess he was busy, what with the pillaging and conquest and all. And this leads into the scene that warranted the trigger warning above, because he demands a kiss from his captive. The immediate result is that Jirel curses him out and, despite having her hands bound, lashes out with her spurred boots and her knees and elbows, walloping the men holding her and even succeeding in briefly braking free. But Guillaume descends from his captured throne, grabs her, and forcibly kisses her.

Jirel is a grade-A badass, though, trying to fucking bite him to death like that. But she’s knocked unconscious and dragged away to what had been her own dungeons.

Pausing briefly, let’s talk about the sexual assault here. This is the only actually portrayed assault in the story, though the implied threat of rape looms large in the story and is explicitly discussed a little later; still, I think it’s worth pointing out that it’s not meant to be titillating to the reader, but rather is described as an actual and serious affront to Jirel’s person and dignity. Similarly, Jirel’s reaction is not typical for a woman in a pulp story facing an outrage like this; she is furious, and tries to kill Guillaume with her goddamn teeth, after all. We’ll talk about it more at the end, but I think it’s important to note that Jirel’s actions in the story are motivated by this assault, much more so than the simple fact that she lost her castle and position. Just keep that in mind as we read on.

Jirel wakes from her stupor in a lightless dungeon deep beneath her castle. She surveys the room in the dark, feeling her way along the edge of the room and finding a small wooden stool which will serve her as a weapon. Then, action-oriented as always, she makes her move:

Jirel creeps through her silent castle carefully, wracked with furious hate at the memory of Guilliaume and the kiss. Jirel, like all true sword and sorcery heroes, is always a hair’s breadth away from titanic berserker rages, and it’s only with effort that she forces her volcanic fury back down into the pit of her stomach. A plan is forming, as told by a wolfish grin she wears as she seeks out her rooms.

The Roman greaves are a nice touch, and help situate us in time and place (even if it doesn’t make a lot of strict sense). Between the name of Guillaume and the “not long past” days of Rome, we’re in France, although there’s definitely more of a high medieval feel to Jirel and her adventures than, say, a Merovingian setting. But still, there are two important points here. First, we’re in a savage age of warlords, lawlessness, and violence, the kind of thing that arises after the fall of an orderly and powerful Empire like Rome. Secondly and much more importantly, I’d argue that this brief scene subverts the important fantasy trope of the Chivalric Hero’s arming ceremony, and is in some ways the first clear and explicit articulation of sword-and-sorcery’s difference from traditional fantasy.

A chivalric hero is defined their equipment – they bear armor and arms that, in addition to signifying social status and prestige, also serve to symbolically elevate and separate their heroes from the rest of the world. A chivalric hero encased in steel contrasts with and indeed rejects the softness and vulnerability of the human body, while also placing them within a milieu of honorable and romantic combat. Similarly, the investiture of a chivalric hero with their armor and often special or ancient weapon represents a numinous, spiritual aspect of their being; again, they are transformed into something more than human.

Contrast this with the hero of sword and sorcery – yes, they have armor and weapons, but they are interchangeable, tools to be used and discarded, mere accessories to the true strength of the the S&S hero, their body and its native, inherent strength and vitality. A chivalric hero is strong, of course, but their heroism is superhuman, signified by the rejection of the body in favor of a manufactured, expensive, and inhuman carapace of metal. The S&S hero embraces their (often admittedly nearly mythic) body. And here, in this scene, we have Jirel explicitly inverting the famous arming ceremony of chivalric romances – she is unattended, and must strip her battered armor off on her own, a difficult task that requires considerable effort and contortions to achieve. You can envision her casting off her grand gothic armor, all fluted edges and glittering layers, the sort of thing that takes a lot of people to put on and take off properly. And what does she replace it with? Doeskins, utilitarian chain mail, and the greaves of a dead empire. These are the trapping of a reaver rather than a grand and noble leader of men! I think it’s a key scene in the history of fantasy in general and sword-and-sorcery in particular, a masterful and efficient expression of a break with the romantic ideal, replacing it with a grim, brutal, and hard-boiled expression of rugged heroism instead.

Emerging from her room as a true sword-and-sorcery hero, Jirel creeps through her dark and silent castle, realizing that her enemies must have spent the night feasting and partying and are now probably sleeping it off. She briefly considers just wrecking their shit while they sleep, but she puts it aside – Guillaume must’ve left SOME sentries, and she figures she wouldn’t be able to kill him without getting captured. She’s got a different plan in mind. She seeks out her priest, Father Gervase, who is praying at his shrine.

Jirel could possibly flee, but she’s chosen a different path, one that horrifies her priest.

An important fact is revealed here: Jirel is not one of these virginal sword and sorcery heroines. It’s not sex per say that she fears; rather, it’s victimization that she is fighting against. That’s an important point, I think. We aren’t told explicitly what Jirel is up to, but it’s clearly a grim and perilous thing she plans to do. Gervase says he would rather give her up to Guillaume than see her do whatever it is she is planning to do, but she is resolute; she will make a deal with the devil himself for vengeance!

Shriven, Jirel descends again to the dungeons, this time seeking out a secret passage that only she and Father Gervase know about. Both had explored it some before, the priest farther than she, and it is a terrible, unearthly place, full or horror and inhuman evil, and it is into this that Jirel will venture! Just fantastic sword and sorcery stuff, isn’t it? And Moore, who has real keen eye for weirdness, really delivers here; Jirel enters a weird corkscrewing tunnel, experiencing strange sensations, altered gravity, and weird animate clouds of darkness that seem to emanate purest sorrow. It’s a great section, and Moore spends the time necessary to convey that Jirel is not merely crawling through a tunnel – she is leaving our world behind and going someplace else.

She reaches the end of the tunnel and feels an immensity around her, as if the tunnel had opened into a great and limitless space. Everything is still perfectly and oppressively dark around her, and she actually feels a constriction around her throat when she tries to step into it, nearly choking until she removes the crucifix at her throat. And while some may balk at the mundanity of a cross having some power over this place, I think it works on a different level – it is only when Jirel rejects this symbol of the normal world and casts it aside that she can see this new, strange world, a very thematically appropriate thing for the story.

First off, she’s crawled down a tunnel into another world – there’s a sky and stars and topography. That tunnel has led her out of the known world into some place very different from our own. And secondly, she’s immediately attack by a bunch of horrible little freaks gnashing at her heels. Her blade goes snicker-snack and she squishes a bunch of the gross little things, disgusted at the sensation of their bursting bodies. Then she steps out into this weird unearthly world, and discovers that the gravity is indeed different; she’s soon leaping with great bounding strides that would be impossible back home, speeding away across the plains towards a weird shaft of light that she’s spotted in the distance.

This is a long section, and I hope you have the patience to enjoy it; it’s basically a description of this weird-as-shit place and the strange, horrible things that live there. Strange pale naked women with sightless and senseless eyes leap froglike through a marsh, rivers murmur with terrible voices in alien languages, and other horrors abound. It’s a very Boschian vision of Hell, uncanny and very weird. Jirel eventually arrives at a the light, which turns out to be a tower made of weird, solid light, where she finds a horrible demon-thing that takes her shape. She senses its menace but still persists in her quest and demands a weapon that she can use against Guillaume, and the mirror devil tells her that what she seeks is in a temple on an island in a lake.

There’s more travel descriptions, and she encounters more horrible things as she goes, including a herd of blind horses that scream the names of women as gallop across the plains. It’s all extremely phantasmagoric, just top-notch weirdness in my opinion. Then, she finds a lake, and spots an island with a building on it in the distance. She crosses a strange bridge of solidified darkness and comes to the temple on the island in the lake.

So this is the titular Black God: a weird, sexless cyclops carved of unearthly stone, its alien lips pursed for a kiss. Oddly phallic too, a one-eyed monster and all. But it’s pretty fuckin’ weird for all that, huh!? A strange consciousness seems to live in the statue, and a horrible compulsion steals over her. Even the architecture of the little temple seems to draw her in, towards the smoochin’ statue.

There’s the scene that inspired the cover! It’s a strange one, for sure, Jirel kissing a weird statue; good weird image, huh?

Something is given to Jirel through the kiss, something terrible and alien and deadly. She flees, sickened and terrified, sensing that she is now bearing something horrible within her from the statue’s kiss. But eventually the panic subsides, and she smiles with grim satisfaction, knowing that she has her weapon.

She flees the twilight land, fearing instinctively the coming of its alien dawn. She also seems to know that there’s a ticking clock with this weapon, that she must pass it along to its target or it will destroy her. The fuse has been lit! She arrives back at the tunnel, slaughters more horrific little things, and then clambers through the weird passage, again experiencing weird dizziness and odd gravity as she travels between worlds. Eventually, she arrives back in the dungeon of her own castle, and what does she find there?

Weak with the strange evil inside her, she stumbles towards Guillaume.

As they kiss, Jirel feels her strength and peace of mind returning as she passes on the Black God’s Kiss. And, similarly, she witnesses the effect that it has on Guillaume.

The horror spreads over Guillaume – his body grows rigid and grey, he shudders and bleeds. He utters an inhuman and unholy cry of some alien emotion as the kiss destroys him. And then, a horrible realization comes over Jirel.

And that’s the End of the Story.

Now, right off the bat, we have to confront the kind of uncomfortable nature of this ending. Jirel, in fact, had been in love with Guillaume, had confused her passion for hatred, and in so doing had destroyed the man she actually loved. It’s not an easy thing to talk about, because of course Guillaume is not a good guy, what with the unwanted kiss and all, and a woman falling in love with her rapist is, of course, a pretty vile trope. But compare it to Moore’s debut story, “Shambleau,” where the female monster and Northwest Smith share a romance that is absolutely destructive. Love as a deadly and destructive force is obviously something that Moore had thought a great deal about and was a source of much inspiration for her, so I think we have to take it seriously in this story; she’s not simply recapitulating a sexist trope here, but rather trying to dissect and examine power and love and relationships, like she does for many of her stories.

I think there’s an important resonance here between this work and Moore’s sci-fi story that we talked about last week too. In “No Woman Born,” the central conflict of the story arises out of the inability of the men in Deirdre’s life to understand or even communicate effectively with her. A similar thing is happening here, I think. Jirel, a woman, a warrior, a ruler, is in a position of absolute power, one held through sheer force of her body and will. This position is upended at the very beginning of the story, Jirel put in a position of weakness and at the mercy of Guillaume, who has led his army to victory against the castle of Joiry and its ruler, Jirel. Neither of them are capable of dealing with the other as equals in this case; Guillaume treats her as mere spoils, which of course Jirel rejects. Both are violent warlords who live lives of violence – in later stories, it’s made clear that Jirel rules through strength, and that her men (all rough warriors themselves) follow her because she is a ruthless and powerful soldier. Trapped in these roles, they cannot see that they are very much alike.

And importantly, it is not sex that Jirel fears, a departure from a lot of fantasy (and fiction), where a woman’s virginity is a sacred thing. Jirel has fucked, she says as much to her priest. What she rejects is that she would be a mere plaything for a man, used and then disposed of. The conflict here is about power and dominance, and how these two people are undone by the structure of their society and their positions in a martial culture and time. You don’t want to get TOO biography-minded when pulling apart a story, but this theme of a strong woman coming into conflict with men and the world of men is such a prominent part of Moore’s writing that it would disingenuous not to say that there’s probably something very personal there, right? An obviously powerful and talented writer having to battle her way through a very sexist industry is something that Moore certainly experienced. Perhaps there’s a message in here about not letting your rage at assholes force you into doing something you regret later.

You might understandably find the ending rough, but you can’t deny that Jirel is a fantastic character, and the fact that she was written in ’34 at the HEIGHT of Conan-mania is really truly remarkable. A woman warrior that is not some weird virginal or sexless monster and who does not rely on magic or some cop-out bullshit is rare today, let alone back then. Jirel is a fuckin’ badass warrior, strong and tough and deadly all on her own because, presumably, she’s just good at killing things. That’s incredible! No wizard or magic chastity vow has given her her powers – she’s just Jirel of Joiry, warrior and warlord, and she will straight up kill your dumb ass if you get in her way. Moore wrote six stories about her, and while they’re all good, I think this is very much the best of the bunch. There’s just something really vital and exciting about the character, and she steps fully formed into the story right away.

And as weird fiction, I think this story delivers too. The scenes of the weird hell world that she travels to are really very strange and mysterious, and they make an interesting counterpoint to the Lovecraftian alien-gods that are more common (especially now) in both weird fic and its subgenre of sword and sorcery. I mean, there’s something very alien about the statue and, phallomorphism aside, I think it’s a very successful evocation of weirdness there, genderless and puckered up in the middle of a strange temple in a lake. Moore is really unparalleled at conveying a sense of oddness without recourse to the more cliched approaches you sometimes come across in Weird Tales. Similarly, her inventiveness and thematic approaches to her stories are just endlessly interesting to me.

I’ve had a really great time with this Moorevember stuff, and have really had fun rereading these absolute classics of hers. Farnsworth Wright was very much correct about putting her name up there with Blackwood and Lovecraft – she’s really one of the 20th century’s greatest genre writers, a true master of the art of the weird! But of course adventure calls, so we’ll have to leave C.L. Moore behind as we wade into some more yuletide sword-and-sorcery in the weeks ahead! See ya’ll next time!