Break out the pumpkins and skulls and eldritch horrors, it’s October, which means it’s fuckin’ spooky season again, baby! And, as is common ’round these parts (i.e., Austin Texas) it’s still in the goddamn mid 90s during the day time, temperatures that are not particularly conducive to the traditional Halloween spirit. So, as in years past, I’m gonna try and get into the spookemup mood by focusing on some particular favorite weird stories of mine, and we got a fun lil’ one this week: it’s “Cellmate” by the great Theodore Sturgeon, from the January 1947 issue of Weird Tales!

Now, we’ve talked about ol Ted Sturgeon just a few pulp strainers ago in the “The World Well Lost” post (number 21 in this series), so we don’t have to spend too much time on him here, biographically – he’s great, one of the absolute top-o-the-heap sci-fi writers of the 20th century, but much like Bradbury, he flit around stylistically (and financially), placing stories where he could. He appeared in the cross-genre pages of Weird Tales with eight of his stories, and this one, Cellmate, is his first appearance in the magazine. It’s also, I think, probably his absolute “weirdest” of the bunch – a lot of the other Weird Tales sturgeon work is very much more science fictional, but this one is basically a straight up weird monster story.

Before we dive in, though, we should take a moment to reflect on Weird Tales. This is a particularly unique iteration of the venerable ol’ mag, and one from much later than I usually sample from. We’re in 1947, a remarkable time in the history of the pulps (in general) and Weird Tales (in particular). The great (and enormously important) editor Farnsworth Wright was long gone, having handed the reins of editorship over to Dorothy McIlwraith in 1940 (and then promptly dying of complications from his Parkinson’s disease). Now, we’ve also talked a little bit about Dorothy McIllwraith before (most thoroughly in last years’ discussion of Fritz Lieber’s “The Automatic Pistol“), so we won’t spend too much time on her here, but, sufficed to say – Dorothy McIllwraith is a hugely important figure in the history of weird fic, someone who was able to navigate a pulp magazine through not only the paper shortages of WWII but ALSO the rise of television (for a while, at least). No mean feat!

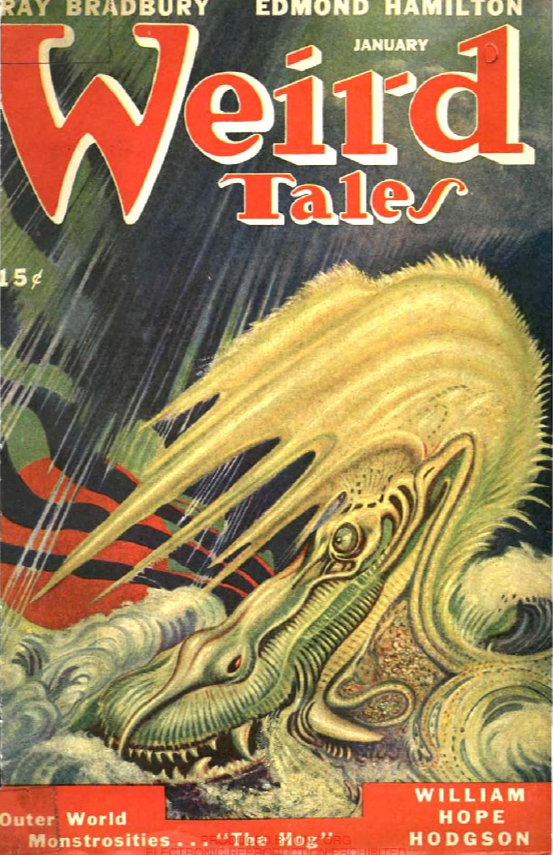

How about that fuckin’ cover, huh? Great, wild stuff from A.R. Tilburne, one of the stand-outs from Weird Tales covers, in my humblest of opinions. This is a perfect example of real weirdness – some kinda weird sea monster? In a storm? Who the hell knows what’s going on, but the mastery of linework and style here is c’est magnifique, n’est-ce pas? I love it, 10/10, nice work A.R.!

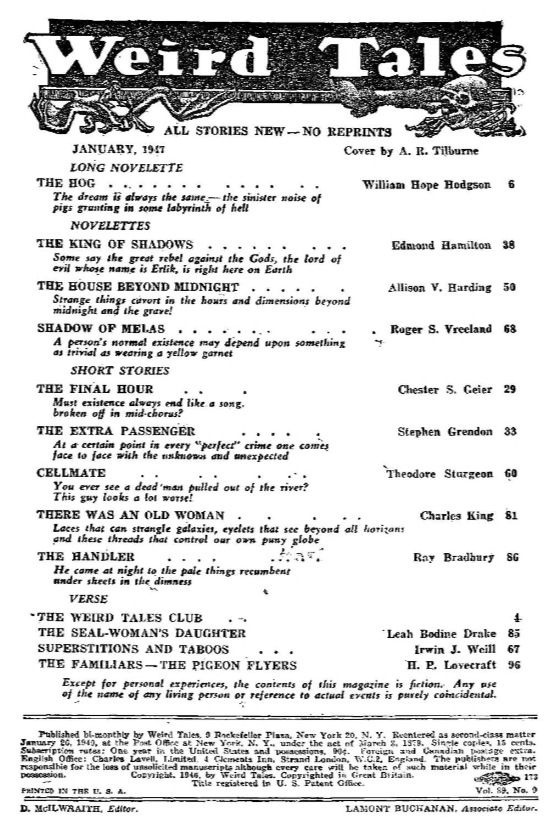

A quick glance at the ToC shows us some things:

First off, this is a *much* slimmer Weird Tales than we’ve ever seen – we’re well into the sub-100 page issue era, something unheard of in the glory days before the war. It’s also worth noting that this is now a bi-monthly mag (by which I mean it’s only six issues a year), so you’re getting a lot less weirdness over the course of the year. I mean, it’s lean times in the magazine world, and only getting leaner. Of course, the magazine is also cheaper than it had ever been – fifteen cents in 1947, when it was a quarter a decade ago!

Now, there’ still some excellent and exciting writing going on here – you’ve got Sturgeon and Bradbury, and Hamilton is still slugging away, one of the last of the old generation still writing. Charles King there is an interesting figure, another sci-fi heavy guy who bled over into Weird Tales, and the story in this issue from him is likewise a good one. But it’s interesting to me that the big center piece story this issue is a reprint from William Hope Hodgson, maybe a cost saving measure but also, maybe, indicative that Weird Tales was definitely having a hard time competing against the flashier (and better paying) sci-fi mags out there. That’s also probably why they publish two chunks of Lovecraft’s longer poem “The Fungi from Yuggoth.” In fact, they’re tiny, so I’ll just give you a bonus and reproduce ’em here:

Like I said, these are two smaller sonnets from a larger work. Lovecraft always thought of himself as a poet first and foremost, and in these I think he does actually end up transcending that affectation. I think they’re good, and taken together in the whole singular piece (which is 36 sonnets long, in total) it’s a pretty phenomenal piece of weird poetry. I also think it’s Lovecraft directly responding to T.S. Eliot, but that’s a subject for another day!

But enough! On to…CELLMATE, by THEODORE STURGEON:

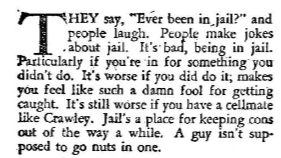

Lookit that title illo – that’s weird right there, yessir! On first past, you can’t really even tell what’s going on here, although by the end of the story this’ll make more sense. But for now, it’s a good bit o’ visual weirdness, and I also think it nicely captures the lonely grimness of prison too – the inky black walls, the high narrow-barred window, even the institutional-lookin’ bed frame thing in the foreground. Nicely executed work from the inimitable Lee Brown Coye!

The beginning of this (pretty short) story wastes no time:

We’re introduced to our narrator, a fairly run-of-the-mill hard boiled criminal who, we’ll learn, is a basic low-level thug, a violent guy who spends a lot of time in and out of jails for various offenses. He’s doing 60 days for some kinda crime (he tells us not to worry about it, which is a surefire way to make you worry about it, right?) when he gets saddled with a cellmate…Crawley.

How about that for a description, huh? It’s very strange. Average height sorta guy, but with spindly limbs, a long stringy neck, and a humongous chest. And the narrator makes it very clear that he’s not merely barrel-chested or anything – he’s abnormally, even freakishly proportioned, a “humpback with the hump in front.” A very strange figure, and with the personality to boot – weird voice, weird breathing, something off-putting and unnerving about him. Our narrator takes an immediate dislike to him.

Crawley ain’t been in this cell thirty minutes, and he’s already acting weird. Again, Sturgeon has a real pen for this kind of stuff, these extremely odd little details – the weird, echoey, resonating scratching, and the way he’s described as “burrowing his fingers into his chest” (emphasis mine) is very, very odd. But, anyway, our narrator has informed Crawley that he gets the top bunk (the worst), but Crawley just keeps standing there, lookin’ dumb and scratching, while everybody listens to a radio soap opera that one of the guards is playing loudly. As an aside, it’s those little touches that make Sturgeon so great – the section about these prisoners having nothing else to do but listen to some dumb shit on a radio, night after night, is good writin’ for sure, really captures the banality of jailhouse life.

The radio show ends, and it’ll be lights out soon enough. The narrator is wondering why Crawley hasn’t gotten into his bunk yet. He’ll get in trouble if he’s not in when the guards come by for the final check, not that HE cares. Hell, he doesn’t even like Crawley!

Strange! Maybe our narrator is just a big softy after all?

In the morning, our narrator hops down out of the top bunk, and immediately sees something weird:

Understandably put out by what he’s seen, our narrator decides he truly, sincerely, does not like his new cellmate. When the food cart comes around, he hatches a scheme that he’s going to take Crawley’s food as well, chortling about how he’ll starve him out until, eventually, the guards will be forced to take him away to the hospital and he’ll be left along. But while he’s chortling about this scheme to himself, he starts to feel some eyes on his back…like Crawley is staring and staring and staring…and then he get the idea that he feels TWO sets of eyes…four eyes, looking at him…but it’s only him and Crawley in the cell…!

His panic builds, as does his belief that he’s got two pairs of eyes on him, but his horrific reverie is broken by the food cart coming by. He gets his own food, then grabs Crawley’s, just like he’d planned…but he still feels the horror of the eyes, and the loathing that they elicit. He briefly contemplates beating Crawley to death, but then:

Aww…another nice thing! Rather than squashing his weird cellmate like a bug, or even stealing his food liked he’d been planning, he gives him some food, and even shows him how to improve its quality, lets him eat on the bunk, everything all nice and sweat and domestic!

Later that day, our narrator hits on another plan to get Crawley in trouble and out of his hair. The prisoners have to keep their cells and their messkit clean, see, but of course Crawley doesn’t know that and, even if he did, doesn’t seem capable of doing it anyway. So our narrator is going to scrub half the cell, and clean his own messkit – the guards, familiar with his habits, will recognize that Crawley isn’t cleaning, and keeping a dirty a messkit is a punishable offense, so he’ll get sent down to solitary. Yes, a sterling plan! So our narrator commences to clean, gets right up to the half-way point of the cell, and then…

AGAIN our violent criminal ends up doing something nice for Crawley, basically unbidden and, of course, unthanked. Weird how that keeps happening, huh? Especially since, after each incident, our narrator seems to be more and more convinced that he hates Crawley, that he wants nothing to do with him at all. And yet, he keeps on bending over backwards for him, helping him out at every turn.

This kind of wild, crazy level of helpfulness from out narrator towards Crawley continues later when, during an outdoor period, Crawley just straight up tells our narrator to buy him four candy bars (“two marshmallow, one coconut, and one fudge”). And that’s WITH our narrator’s carefully shepherded tobacco money too, mind you. At first our narrator laughs in his face; why the fuck would he do that, spend his own money on candy for a guy he absolutely hates…but he does. In fact, he goes out of his way to make sure he gets the candy. He also seems unable to talk about Crawley to anyone, either – he thinks he’ll get some good laughs telling his buddies in the yard about this freak he’s bunking with, but for some reason he just never can get around to talking about him.

Later that night, after helping Crawley with his blankets (effectively tucking him in), our narrator hops up into the top bunk and tells Crawley he shouldn’t talk to himself in his sleep, which results in a truly weird scene:

I mean, that’s weird, huh? A really strange and unearthly scene, this insane, grating, screaming laughter, and when he looks, Crawley’s mouth is shut, the laughter coming from somewhere deep inside his chest, an unearthly sound that doesn’t make any sense. Our narrator feels himself losing his grip, the laughter is driving him crazy, and it only stops when he, apparently, passes the fuck out.

He comes to sometime in the very early morning, three or four he thinks; he feels like he’s been slugged, groggy and strange, and he hears Crawley talking in his bunk.

And someone else answering!

You might have guessed where this is going, though I think it’s weird enough that it kept me guessing, right up until the reveal. It’s very weird, and honestly spooky, especially after the weird hollow laughing from earlier – imagine being this thuggish narrator, waking up from something and hearing two voices where you only expected one…spooky shit! Our narrator carefully, quietly tries to investigate…

Crawley’s weird clamshell chest is some kinda kangaroo pouch for his weird stunted conjoined twin brother! And whatta twin! It’s the size of baby, but with a shaggy head of hair and a long, lean face and a fanged mouth. It’s a legit monster. And, moreover, our narrator intuits what this thing is, and what it’s been doing:

It’s some kinda psychic dominator stunted twin, living inside of Crawley! If you go back to the picture at the beginning of the story, you’ll recognize the scene it’s depicting now, and see that it’s actually pretty faithful to the story. It’s pretty wild and, like all great reveals in weird fic, it makes you go back into the story and think about the strangeness you’ve read in a slightly different way – clearly this little monster twin has been controlling our narrator from the get-go, getting him to give up the bunk, give big Crawley the food, etc. It also seems to imply that our narrator has probably seen this thing before – it’s why he knew about the four eyes he felt, but he’d probably been ordered to forget it. So, why does little Crawley let him remember now?

Because it’s jail break time, baby!

Little Crawley has put our narrator into berserker mode – he kills two guards with his bare hands, uses a third as a human shield, and causes the death of at least one prisoner from a ricochet round. He’s a one man riot, impervious to pain and utterly fearless, doing everything he can to cause chaos and attract attention.

And that’s the end of “Cellmate” by Theodore Sturgeon!

First thing first: is this the earliest example of the “evil secret conjoined twin” trope in fiction? There’s the movie Basket Case from the 80s, a real goopy gory (and funny) monster movie about an evil conjoined twin that has been removed and is being cared for by his more normal brother, and then there’s that X-Files episode, or that recent movie Malignant. Are there earlier examples though? The interesting thing in all of those, of course, is that the tiny twin is almost all monstrous id, right, a kind of primal and murderous atavism that is either autonomous or takes control of its sibling to do evil, whereas here in this story, the twin and the larger brother have a working relationship, and in fact the littler evil twin is by far the smarter of the two.

Honestly, for me, Crawley’s creepiness come more from the weird hinged chest cavity than from the tiny guy living in it…I mean, yeesh, that’s just plain weird you know? Like big Crawley is a straight up mutant! Oh, there’s another example, Kuato from Total Recall, who is also an example of the little guy being the “boss” (although Kuato, of course, is a good guy).

In fact, in terms of “evil conjoined twin,” the only earlier example that I can think of is the apocryphal and almost certainly fictional story of Edward Mordake, who supposedly had an evil (and female) second face on the back of his head that whispered horrible suggestions to the otherwise morally upright Edward. It was originally published in The Boston Post in 1895 (you can see it here), and there’s lots of obviously made up stuff in the whole article, but it is a weird and interesting precursor to Crawley here.

But, aside from that, I think this is some great weird fiction – the prison setting is fun, spare and claustrophobic, but the narrator’s familiarity with it makes it all seem drab and kind of humdrum. Sturgeon, who is a master at getting into a character’s head and finding their voice, does a great job with the narrator – he’s a violent but somewhat jaded thug. He’s got his routine and he’s used to coming and going from jail all the time, so the imposition of weirdness in the form of Crawley on his “normal” life is really stark and unmooring.

And man, Crawley is just WEIRD right off the bat – the physical description is very strange, with his odd proportions, and then his behavior is just very odd and kind of alien. Like I said, it all makes sense in hindsight – why bother to even try to behave normally if you’ve got a psychic dominator twin living in your weird chest pouch, after all?

Now, you don’t wanna get all Freudian psychoanalytical about this stuff BUT as mentioned in the last Sturgeon write-up I did (here!), ol’ Ted DID spend a fair amount of his time interrogating queer relationships between men. As mentioned, he himself was what we’d call “bisexual” (he certainly would not have used that term, however), and had a number of sexual and romantic relationships with men (while being married with a family to a woman). In “The World Well Lost” we have a kind of interesting mirror-universe version of Crawley and our Narrator, although one not so freakish. Still, there’re some similarities between the two couples; there’re both confined together, there’s a disparity between their physical attributes, etc., and the themes of homosocial male relationships undergirded by “something else” are present in both. Why does the Narrator keep doing so many generous kindnesses for someone he also simultaneously feels repulsion for? You don’t want to read too much into these things; Sturgeon, a working writer, liked to eat hot meals indoors, and so he wrote stories that he could sell, and sometimes that means adhering to certain narrative conventions and such. But he was also an artist, and finding a topic or theme that interests you is a key to making good work, so the thread of his own experiences is certainly worth keeping in mind when reading his stories.

It is a fairly short story, and while I would say that the weirdness is on simmer for most of it, there length means that there’s not much of the slow, mounting dread that I normally like in a weird story. But it works here, particularly because the reveal really puts all the previous actions of the narrator in a different light, kind of retroactively imposing weirdness on them. Speaks to Sturgeon’s skill as a writer that it works so well, that he’s willing to let the scenes just play out fairly straight because he knows that what is coming will force you to look back at them and recognize what was going on.

And, while the slow burn isn’t really there, the creep factor IS high; I think this story is flat out scary, especially the weird laughter scene that builds to the climactic reveal of little Crawley in the chest cavity. The narrator’s murderous fugue is well done too, and the idea that Crawley has escaped and is back out there amongst us is good, classic Weird Tales stuff.

Anyway, I think it’s a good start to this Halloween season, an inventive, weird, and sometimes scary story that will, hopefully, get us all in an appropriately spooky mood!