Despite a general lack of Halloweenishness in Austin right now (summer is lingering here, dry and hot and miserable) I refuse to let it deter me. I SHALL fulfil my sacred vow of rambling interminably about pulp stories I like! And today is a fun one, a Lovecraftian story from Carl Jacobi: “The Tomb from Beyond” in Wonder Stories, Nov 1933! Archive.org remains down, so that link takes you to a google drive address where you’ll probably have to download the whole issue.

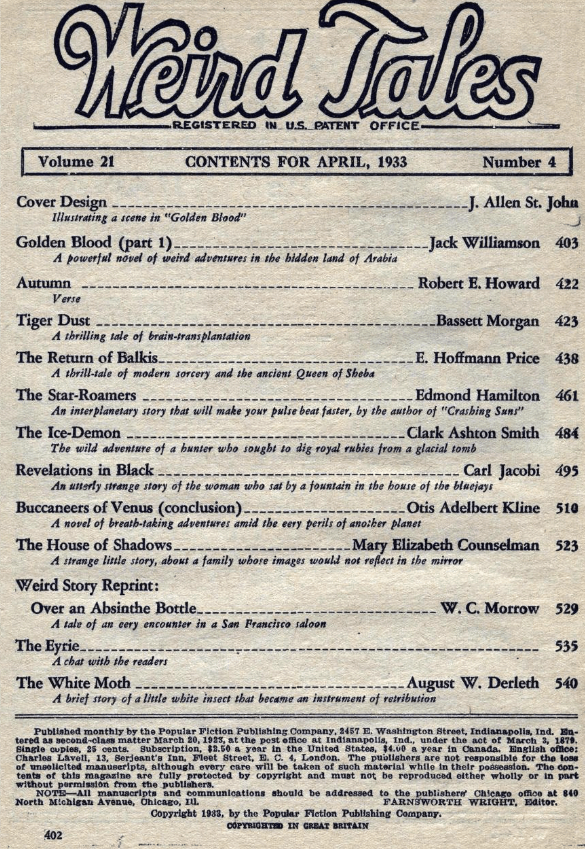

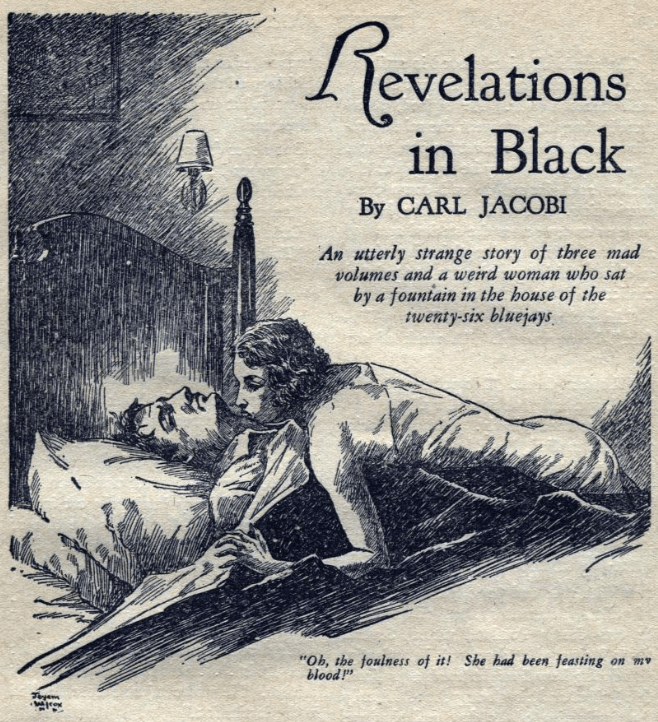

I’ve been on a Jacobi kick lately – you can read some of my previous musings on his stories “Mive” and, more recently, his vampire story “Revelations in Black.” Obviously I like his paleontologically- and geologically-informed approaches to horror and weird fiction, but I also think he has an interesting take on Lovecraftian-style cosmic horror. Unlike, say, Frank Belknap Long or Robert Bloch, he’s not just aping ol’ HPL’s stuff – he’s inspired by a lot of it, of course, and appreciates both Lovecraft’s fascination with science and Deep Time, but Jacobi does so in his own way, and without the kind of “pastiche-y” quality that a lot of the HPL Imitators seems to fall into. In some ways he’s more of a fellow traveler with regards to Lovecraft’s cosmicism, rather than just another acolyte, someone whose approaches and style are his own, even when the subject matter is inspired by Lovecraft’s work. Also, I frankly think he’s a good writer – his scenes and impressions and descriptions are fun to read and interesting to think about, and that’s worth a lot, in my book.

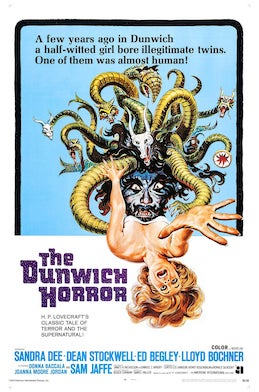

Today’s story is interesting because it really reads like a Weird Tales rejection that ol’ Hugo Gernsback caught on the rebound for his sci-fi magazine, Wonder Stories. There’s very little “science” in Jacobi’s story, and I even wonder if Gernsbeck didn’t insert some of the rambling bits about “the Fourth Dimension” that are in there.

Gernsback, of course, is the Grand Old Man of Sci-Fi (or “Scientifiction” as he preferred), an enormously influential figure in the field who, basically, shepherded the genre into being in the pages of his magazines. His first endeavor, Amazing Stories, was one of the first real competitors of Weird Tales, siphoning off both its more science-flavored stories as well as the “planet stories” that had been so contentious among Weird Tales‘ readers. Gernsback also had the great luck/foresight to publish what is probably Lovecraft’s single best story, “The Colour out of Space” in Amazing Stories in 1927, during one of Lovecraft’s many attempts to get our from under Wright and Weird Tales. Of course, it kind of backfired, in that Gernsback only paid him only $25 (~$500 in 2024 money, which I’d kill for btw) for a truly remarkable story, and extremely late at that – Lovecraft soured pretty quickly on the dude he dubbed “Hugo the Rat” in his letters, and never published with him again.

What’s fun is that, even in 1933, you can see that the sci-fi and weird tales fandoms are in the process of peeling off, but haven’t quite separated yet; check out this kind of funny message Gernsback sticks up at the front of the story, using his usual pseudo-technical jargon (“story interest is highly developed”) and also his somewhat backbreaking attempts to reassure the readers that this IS a sci-fi story.

Yes, “plausible science” indeed! It’s a funny bit of genre boundary work, an important but understudied aspect of the pulp magazine era.

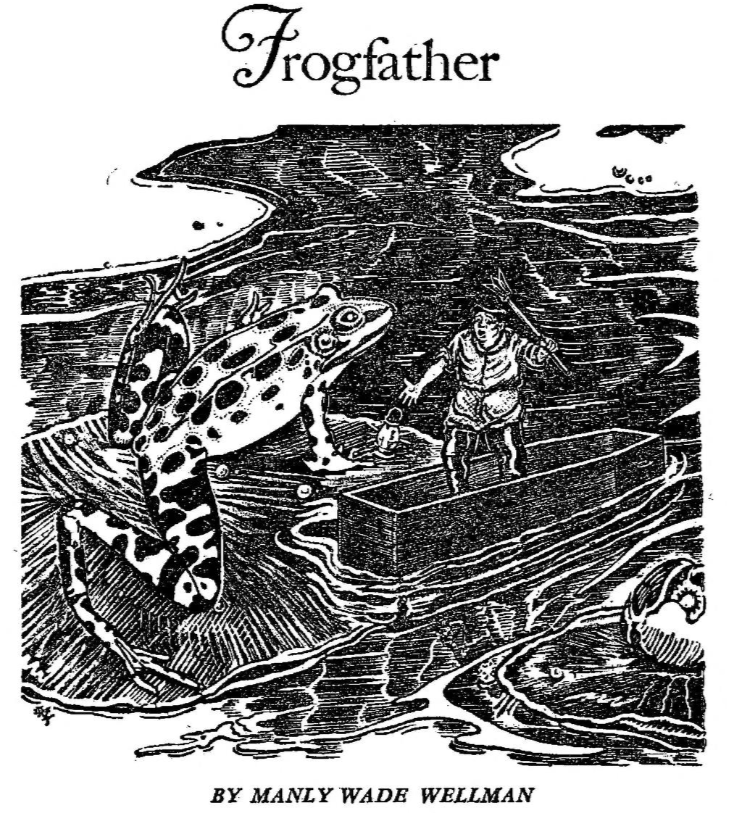

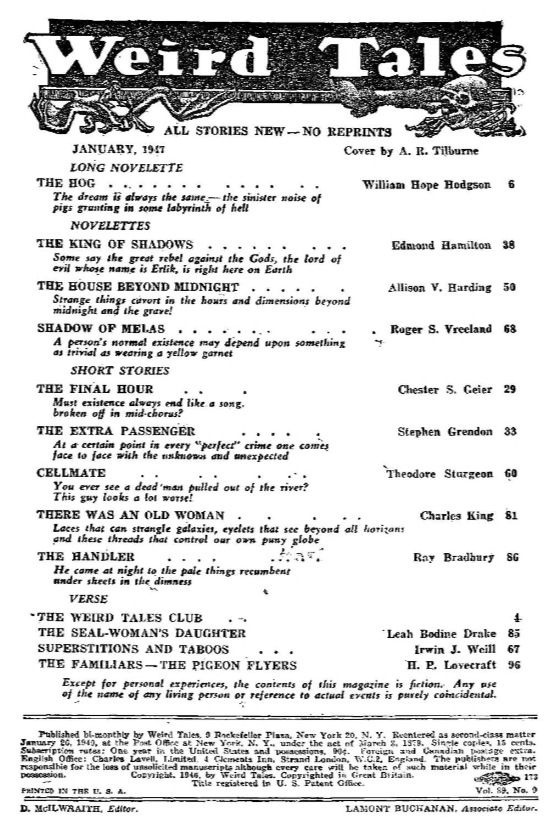

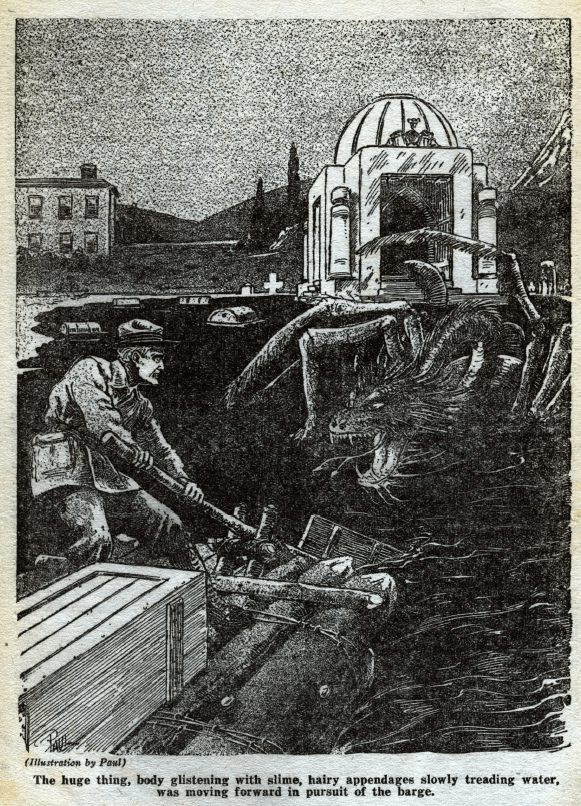

We’ll forgo the ToC this week because there’s very little of interest there (although Hamilton’s “The Man With X-Ray Eyes” is in this issue, which would later be turned into a pretty great movie with Ray Milland that you all should go watch). So we’ll get into our story right away with a quick look at the climax-spoiling illustration that accompanied the first page!

Feels like this one is a particularly egregious example of the spoiler genre of illustrations these mags like to do, since it commits the cardinal sin of Showing the Monster before the story is ready for you to see it – as you read, you’ll quickly be annoyed that this fucking picture just goes and gives away the weird monster right off the bat. Very stupid and very frustrating, especially when there are much more atmospheric and strange images in the story that would’ve been way more effective. Infuriating stuff! But, we march onward.

Our story starts with some poor real estate agent type fellow, who we’ll learn later is named John Arnold, out in the middle of fuckin’ nowhere, heading towards some place called Opal Lake. I really like the sense of abandonment and decay that Jacobi evokes in these opening paragraphs – the difficulty in actually getting to this town, Flume, makes it clear that it’s out in the sticks, and the omnipresence of the collapsed timber business makes for a fun, spooky atmosphere…I mean, even the name of the town, Flume, harkens back to a formerly prosperous and industrious time. It’s very much in keeping with that “decayed new england” so popular in weird fiction. And not only is Flume decaying…it’s actually a ghost town!

That’s some good, atmospheric writing here, evoking long, dreary, tiring miles and general abandonment and collapse, the infrastructure rotting in place, the road bad and the trip exhausting. Arnold has hired a car for this last leg, and he’s being driven by a taciturn old Finn, a further bit of alienation – even with another person, Arnold is alone in this landscape, long gone from human company or civilization. As he’s staring out the window, he tries for a bit of conversation:

Gotta pause here to call out Jacobi, who’d studied geology and paleontology at the University of Minnesota, calling out the terminal morraine! Always a treat with him, these little glimmers of earth science!

Anyway, the driver grunts the affirmative – this is indeed Opal Lake, and they’re getting close to Flume. But, as Arnold continues to look out over the rain-spattered countryside, he spots something odd – there’s a second, smaller lake, a kind of half-crescent, not far off of Opal Lake proper. What, pray tell, is the name of that lake, he asks, but the question seems to trouble the driver, who only answers gruffly “that isn’t a lake.” Arnold finds it odd, and is a little annoyed that this guy is being so grim and gnomic, but there’s a bad patch of road and in all the jostling he decides to let it go.

Night falls and they turn a curve and, voila, they’re in the abandoned lumber town of Flume. The car creeps slowly through the silent streets – at first it seems like the man has come to meet isn’t there, but then:

Arnold is a bit taken aback that Trenard neither greets nor thanks him for coming all the way out to the middle of nowhere, but what are you gonna do? The driver is dismissed, and he gets the hell out of Dodge with a quickness, leaving just Arnold and Trenard alone in the ghost town. Trenard offers two paths to his house, one through the woods and one by…the lake!

Well, I mean, how are you supposed to respond to that? Arnold choses not to, and they walk out of town and start heading down a logging road to the house. Trenard lapses immediately back into moody, meditative silence, which gives Arnold a chance to give us some exposition.

Oh hell yes – sunken city? scientific expedition? lost civilizations? undecipherable hieroglyphs? QUEER ARTIFACTS BROUGHT BACK TO NEW YORK?

That is some solid, classic weird fiction stuff right there. The only thing it’s missing is if something strange and mysterious and tragic had happened during the expedition, something…horrific…

Rumors of fuckin’ sea monster attack? Check, check, and check, baby!

Now, me personally, as a writer of weird fic, I’d have left out “sea monster,” just stuck to rumors of a weird death, but nonetheless, it’s fun. Trenard and his partner ran afoul of something off the coast of Borneo it seems, and whatever it was has left Trenard…changed.

Now that’s some Rockefeller/Cloisters shit right there, disassembling, raising, shipping, and then reassembling an ancient tomb from Sunken Dras right there in the backwoods of old timbercountry upstate New York! Weird, huh? People speculate that he’d had a touch of the ol’ fever when he’d been inspired to do it, and then again maybe he’d been driven off the deep end by the sudden death of his sister while he was out adventurin’ there in Borneo too. Either way, he gets good use of this tomb – when he installs it in Flume, he puts his sister’s body in there, among the grand architecture of a lost civilization. You’d think something like that might be a boon for Flume going on, but, nope:

Good solid scene-setting. Jacobi is bringing in his own ancient civilization stuff, with all the attendant weirdness of deep archeological time and hidden branches of human history. I love it!

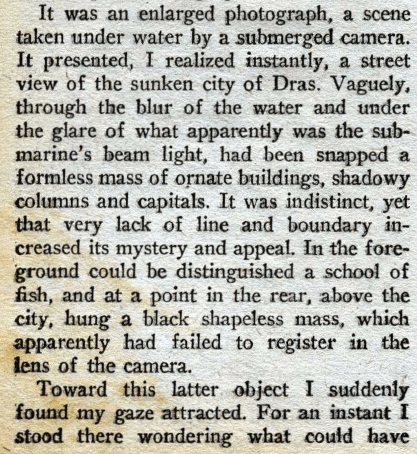

Anyway, they get up to the house, finally, and its big and weird and full of odd stuff. Trenard goes to get some refreshments for his guest, leaving Arnold to look around and do a bit more scene setting. There’s a fun passage where Jacobi does the classic Lovecraftian move of inserting real stuff (Wallace’s famous book The Malay Peninsula), but the real highlight is when he gets a chance to really look as a framed picture on the wall:

Jacobi knockin’ it out of the park here, in my opinion. You can see this weird, blotchy picture, the view distorted by the water, strange ruins getting picked out by the beam of the submarine’s light. It’s very evocative, very strange, and would’ve made for a much better and more interesting title illustration too!

Arnold’s strange revery is broken by Trenard’s return with “a tray of china.” Arnold eats, Trenard smokes a ridiculous meerschaum, and then Arnold tries to get down to brass tacks – he’s here because the company is willing to sell Trenard’s property for him, but he’s got to be realistic about the price he’s going to get, what with it being way the fuck out in the middle of nowhere and all. Trenard understands that, and just needs to recover the costs he sunk into it so he can get the hell out of there. Something is clearly troubling him, and he is desperate to escape from this place.

You’ve probably already noticed that this first part is, at least spiritually, cribbing a lot from “Dracula.” The real estate stuff, the Finn driver dumping him and then driving off, the wild and ruined countryside. I don’t think Jacobi is doing more than simply nodding at it, enjoying the resonance and taking advantage of one of the greatest bits of horror writing in the canon, although there might be a little bit more to it, which we’ll talk about when we get there.

Like I said, Trenard quickly dismisses Arnold’s concerns and basically agrees to accept whatever price they get first, and fast. Definitely seems like one of those “this meeting could’ve been a telegram” sort of things, especially since Trenard says he’s going to bed and they can finalize the paperwork in the morning. He leaves Arnold on his own in the study and, refreshed by his repast, he decides to pull a book from the shelf and do some reading. The book he chooses? Why, it’s Trenard’s own “The Mysteries of Sunken Dras.” He notices some underlined passages:

Two things here: did Trenard underline his own writing here? If so, that’s hilarious…I imagine him penciling in, like “Good Point!” or “Genius” with like a couple of stars. Funny thing to do to your OWN writing, is my point. The second point comes after we get Arnold’s reaction to these insane statements about an ancient civilization’s knowledge of hyperdimensional physics and alternate planes teeming with unimaginable horrors:

Dry and bookish!? Tough crowd, yikes!

Arnold ALSO finds a scrap of paper with, apparently, Trenard’s own notes on it – perhaps he had been going through his book, with its dry and bookish description of ancient ultrascience and transcosmic monsters, and reexamining them in light of more recent developments? The note reads thusly:

Oddly specific thing to be musing about and, not to spoil it, but he ends up being 100% correct. The mausoleum is, basically, a fourth-dimensional portal, and it wasn’t broken by moving the building – he’s brought a portal to hell all the way from the coastal shelf of Borneo to upstate New York! Neat! I really like the hint of another story in here too – what was it that drove out the villagers who had been living in Flume? What kind of weirdness were they dealing with while this weird transdimensional architecture was being installed in their town? Trenard seems little concerned with that, though – he’s more troubled by the thought of his sister’s body being trapped in there with something from…beyond.

As an aside, it’s interesting to me how, up to the early 20th century grave desecration and particularly troubling the remains of the dead was such a huge part of horror literature. I mean, for us today, I don’t think it elicits the same kind of seemingly existential horror that it did for folks back then, you know? I mean it’s gross, sure, but the way people viewed it back then, there’s really some deeper meaning attached to it, you know? It’s interesting, and I’m not sure I’ve ever seen, like, a paper on it or anything.

Anyway, back to the story! We also get a hint about the origin of the smaller, secondary crescentic lake that Arnold had spotted from the car. There’s a leak in the dike bounding Opal Lake, which, uh, doesn’t seem to bother Arnold as much as it should. Like, he’s a real estate agent trying to sell this land, and it’s getting flooded by a faulty dike?

In fact, Arnold just shrugs and goes for a night-time stroll on the balcony overlooking this flood hazard scenic pond…and then it hits him!

Not only is Opal Lake leaking, but it’s flooded Flume’s graveyard, including the mysterious tomb that Trenard brought back from mysterious Sunken Dras. All kidding aside, it’s an evocative image, isn’t it, and the description of Arnold’s epiphany about what those small, regular white shapes are in the water is just fantastic, a real shivery moment in the story, very visceral. Jacobi has a real affinity for moonlit scenes, as we saw in “Revelations in Black.”

So fascinated by this realization, Arnold decides he simply must take a boat ride out to the drowned cemetery IMMEDIATELY. He hops in a little row boat that’s moored to the shore below the house, and paddles on out there. Setting aside the mysterious tomb and the cemetery aspect, a solitary night-time row while the only other person for miles is konked out seems like a bad idea, but oh well!

There’s some more great environmental descriptions of the lake and the environs and the house receding into the night as he rows away, and then Arnold reaches the drowned graveyard:

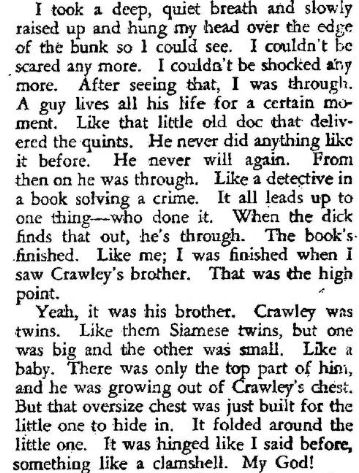

Great spooky stuff, and I can’t blame him for wanting a peek in the weird Dras tomb; I mean, if I’d just read something insane about their dark sciences, I’d wanna get a look too. And what does he see?

Nothin’ but darkness, then a bad stink, and then a hiss, a splash, and, oh, my hands have been gashed to the fuckin’ bone! Jesus Christ man! Bloody hands be damned, Arnold leans into the obvious shock he’s experiencing and power rows back to shore. Back in his room, he iodines and tapes up his wounds and, finally, exhausted, drifts off to sleep.

Bad weather greets him in the morning – if he thought he was going to get out of Flume early, he was mistaken. In fact, given the state of the roads, he might be stuck there for a while, a grim thing given what he’d experienced last night. And, aside from the fact that something uncanny is definitely happening out on ol’ graveyard lake, it also quickly becomes clear that Trenard is kinda off his rocker too.

It’s kind of odd that we’re reiterating the “fourth dimension” stuff here again – I wonder if that was in the original work, of if Gernsback had it inserted (or even, possibly, wrote it himself – he was famous for a heavy-handed editorial approach). It doesn’t really give us much new information, not after the note in the book, although it does give Trenard a chance to be weird and talk a lot of crazy shit, while also being oblivious to his guest’s wounded hands.

Arnold spends a dismal day with Trenard, doin’ up the paperwork and then just kinda hangin’ out, listenin’ to the storm, watchin’ Trenard get more and more freaked out. And then, in the late afternoon, the storm dies, and with the clear weather Trenard seems to reach some kind of sudden decision!

Arnold runs after him, and finds Trenard down by the shore rolling a bunch of huge barrels onto a weird barge like boat. Arnold realizes that Trenard is obviously in the throws of some kind of delirious state, working madly, sweat steaming off him and a wild energy to all his movements. Finally, with the barrels loaded, he pushes off from the shore; Arnold follows in the little duck boat, and sees that Trenard, while generally making towards the tomb, is doing so fairly circuitously, taking the time to pause and dump the barrels into the water – they’re full of oil, and soon the whole surface of the cemetery lake is a vast, flammable slick. When the barrels are all empited, Trenard paddles over to the tomb and opens the vault!

He’s haulin’ out his sister’s body, rescuing it from this weird-ass tomb, and he’s obviously concerned that he’ll need to set everything on fire…it’s a weird scene for sure! Here’s the part where that illustration at the beginning really sucks, because otherwise you might not know what’s happening…hell, you might think, given his preoccupation with his sister’s body, that there’s something going on there, that SHE’S somehow been weirded-up by the tomb and is the danger here! But, no, we already KNOW there’s a weird monster attack coming up (of course, there’s the “sea monster” attack from the expositionary dump earlier, but still…)

Anyway, Trenard is trying to haul out a coffin AND hold the door closed against some kind of implacable force pushing from within…but it’s too strong, and Trenard has to leap back, undoing the mooring and paddling furiously away, while, from out of the black crypt, comes…something…

A spider-mosasaur-thing erupts from the tomb, it’s jaws slavering, ravening with delight. I love the image of a weird hairy, jointed legged reptile thing, it’s a good, solid monster, a little more Robert E. Howard than H.P. Lovecraft – this isn’t weird mass of bubbling protoplasm from beyond the stars, it’s a fuckin’ beast, albeit one of very alien evolution and history…but still, you could see Conan takin’ a swing at this thing, couldn’t you?

The little aside about the critter looking like something “from the canvas of the mas August Schlegel” is a fun bit of Yog-Sothory, I think. Now, there was a real August Schlegel – he’s kinda famous for having translated Shakespeare into German in the 19th century, but this is obviously a different guy (he’s a painter, for one thing). This is Jacobi inventing and alluding to a crazed artist of the past whose work captures something of the preternatural or cosmic beyond our mundane understanding, a trick Jacobi probably picked up from the Weird Tales crowd for sure (Robert E. Howard’s mad poet Justin Geoffrey comes to mind, as does Lovecraft’s Wilcox in The Call of Cthulhu or, more famously, Pickman in Pickman’s Model). This stuff’s like popcorn to me – I’ll eat it up by the fistful.

Anyway, this horror surges out of the tomb and after Trenard and the barge. There’s some good, fairly suspenseful “death race” kind of stuff, with Trenard working the oar on the barge while this big weird monster chases after him. There’s also a fun part where Arnold, watching all this from his boat, realizes what Trenard was afraid of:

That bit is great, and pushes it beyond the simple “grave desecration” point I made earlier. And it makes sense to – I mean, I’m a strict materialist, but if confronted by the existence of other weird dimensions full of crazy-ass monsters, maybe there is some reason to be worried about the body of a loved one being in close proximity to door to another fuckin’ universe, you know!? It’s good weird stuff!

The critter eventually catches up with him, of course, and just as it is leaping up to chomp Trenard, he lights some matches and sets the fuckin’ lake on fire!

Our boy Arnold paddles to shore, leaps out, and in some kind of fugue state, stumbles off down the road, walking back towards civilization. He remembers little of the trek, but form a high point, perhaps the terminal morraine from the beginning, he catches a final glimpse of the lake:

And that’s the end of “The Tomb from Beyond” by Carl Jacobi!

I think it’s a fun story, and while the conclusion is kind of forced (dude thinks he might have to set the lake on fire in case of monster attack, is attacked by a monster and sets the lake on fire) I think Jacobi’s descriptions of the scenery and environment and atmosphere more than make up for it – he’s an evocative writer with an eye for weird, oppressive settings, and the storm, the abandoned landscape, the cemetery lake, all of these are excellently realized here.

Now, perhaps the weirdest part of the story is a bit underdeveloped – I think the idea that there’s some kind of intrinsic transdimensional portal in the tomb that is so fundamental to its architecture that it can be broken down and reconstituted elsewhere, no problem, is a lot of fun, and it’s a shame Jacobi doesn’t do MORE with it than let there be a monster in there. But, even so, the suggestion of the weirdness is fun, and I enjoy what little glimpse we get of it.

I also enjoy the obvious inspirations behind this work too; there’s Dracula, sure, but there’s also “The Fall of the House of Usher” here, and it’s neat to see these being reworked with such a light touch – Jacobi never beats you over the head with them, I mean. He’s just been inspired by some classics to write a story, and he’s turning them into something new and interesting while doing it.

Plus, what makes this a good bit o’ weird fic for me is the fact that there’s lost of strange, unanswered questions in it. Is the flooding of the cemetery just an accident, or is the tomb somehow responsible for this inundation? Remember, it’s a sea monster, basically, so maybe IT is remaking its environment, much in the same way Trenard tried to remake his in Flume. What happened to make the villagers leave? Was Sylvia’s “soul” somehow endangered by being in the weird ass tomb? It’s all good, fun, weird stuff, and I like it! And, while it’s certainly a “fourth-dimensional” story, it never really treads over Lovecraftian crowd; Jacobi is an original writer, with his own ideas and very much his own style, and it’s fun to see a Lovecraft contemporary doing his own thing on the same themes.