The shittiest, dumbest fascists in all of history may be crowing (for now) about their reactionary censorship, but we shan’t let their weepy, whining bullshit deter us – fuck them and fuck all fascists forever! And so, pushing them out of our minds and into the dustbins of history, we shall instead turn our attention to fun, useful, and interesting topics; namely, WEIRD FICTION.

Been a good couple of months since the last of these posts, but we always come back to the topic of classic weird fiction here at the ol’ blog. And, as the most Hallowed of all Eves looms in our future (a scant month-and-a-half away!) it’s time to get down to brass tacks and dive back into the pages of the Unique Magazine, Weird Tales. And this story today is an interesting one, though not without some problematic content, of course. It’s Arthur Burks’ “Chinese Processional” from the 1933!

Burks is an interesting guy, one of the absolute machines of the pulp era who came to be known as a “million-words-a-year” guy for his insane productivity. He wrote something like 800 short stories in his long career, and was famous for his methodical approach to his fiction. That being said, I think there’s actually some fairly nice writing in some of his work (today’s story included), a vibrancy and thoughtfulness to the descriptions and mood he’s trying to invoke.

Doubtless, this is because ol’ Burks actually lived in China. Most of the biographies of Burks focus on his time stationed in the Dominican Republic during the brutal occupation there, a period of his life that inspired him to write some (often shockingly racist) “voodoo” stories that were immensely popular with pulp readers of the day. However, in 1927 he resigned his commission while in China and ended up living there for a while, a period of his life that was an equally strong influence on his writing; I think it gave him a bit more depth and insight into the period and place at least, which we’ll talk about below. His deep connection to China, and specifically to the Manchu dynasts who oversaw the collapse of the Empire in the face of European Imperialism, is evident in the fact that he wrote the preface for a memoir by one of the Dowager Empress’s Ladies-in-Waiting (“Old Buddha” by Princess Der Ling).

But, before we dive in, let’s take a look at the cover and the ToC!

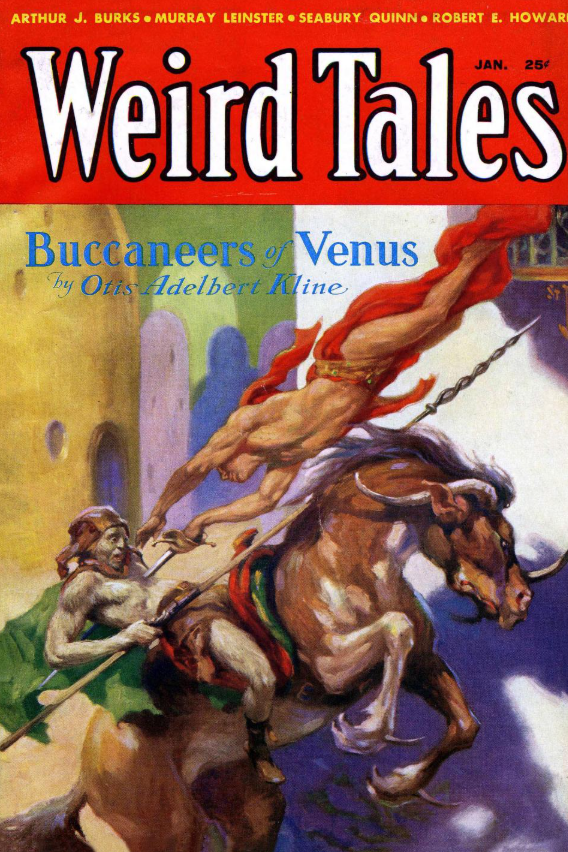

A nice painterly action scene curtesy of ol’ J. Allen St. John. It’s a nice one; I like the shocked look of the goon getting shanked there, and the Venusian beast has a nice sense of motion and heft to it. The only problem with it is that it’s an illustration of one of ol’ Kline’s pretty cash-grabby and pastiche-y “Venus” stories. As far as sword-n-planet fiction, it’s not *bad* per se; you’ll just be unable to shake the feeling that you’ve read basically all this same stuff about another guy, Carter was it? And didn’t it take place of Mars? Oh well; c’est les pulps, after all!

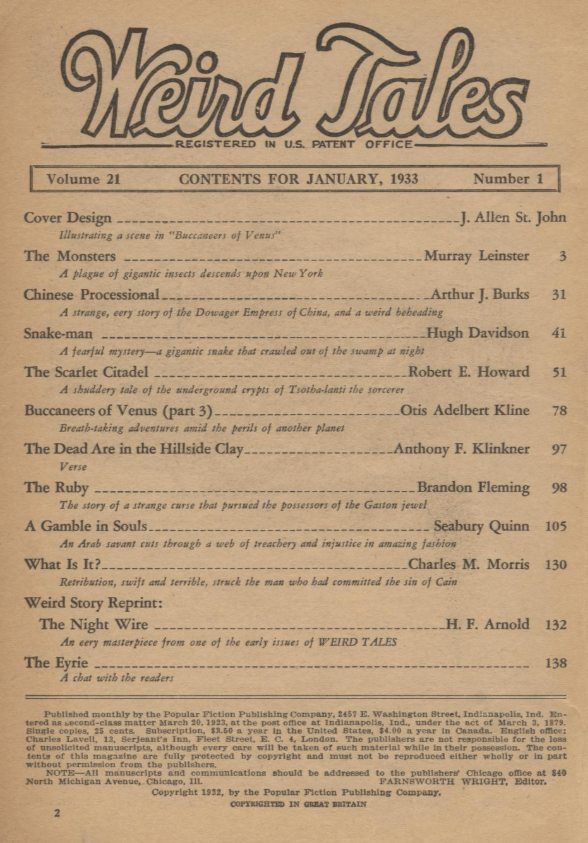

The ToC has some fun stuff here – a work-a-day Leinster story with some Big Ass Bugs, which is always fun, as well as what’s probably my favorite Conan-the-King story, “The Scarlet Citadel.” Also neat to see them reprinting “The Night Wire” again! That’s absolutely one of my favorite weird stories of all time; we talked about it a couple of years ago, if you remember.

But enough of this! On to the story: “Chinese Processional” by Arthur J. Burks!

A pretty brutal title illustration by ol’ “Jay Em” Wilcox here! Also notable in that it’s not *particularly* racist, although of course it is definitely grounded in the pulp orientalism of the day, trading in the brutish menace and cruel savagery of a racialized other. Interestingly, I don’t think you can say the same about the story, and even the tone of the violence, which in this illustration seems to be of a particularly barbaric nature, is different in Burks’ writing. But we’ll get to that!

Our story opens with our narrator musing upon his subtle, innate psychic abilities, something that it seems like Burks also thought – his later life, in the 50s and 60s, included a fair bit of writing about psychic phenomena and supernaturalism. But, our narrator is quick to assure us, even his psychic gifts cannot FULLY explain what we’re about to read!

Right of the bat, we’re introduced to some history about the Summer Palace outside of Peking, a royal retreat where the Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi (known more commonly as Cixi today) went into retirement. Cixi is, of course, a real person, a powerful and fascinating figure who, through a combination of political acumen, ruthless realpolitik, and versatile diplomacy, ruled China for fifty something years, pitting European powers against one another while brutally suppressing reform and dissent. Here’s a picture of her, btw, from 1904:

Burks’ familiarity with the history of the Manchu court is on display in this short but sweet first section; it provides a nice sense of the power of the Chinese Empire and the monumental weightiness of the Summer Palace, I think, particularly where Burks’ points out to us the artificial, engineered nature of the landscape – the hill is human made, as is the vast Kun Ming Lake, speaking to the power of the Emperors who can reorder the surface of the Earth to fit their whims:

It also introduces a major theme that will run through this story: tourism, and in particular the way a we interact with the past when visiting these places. The little aside about a guide showing you where the (much reviled) “Emperor” Piyu was locked away in the Summer Palace, for instance, orients us within a framework of tourism and exploitation.

There’s a real sensuous delight that our narrator is taking from the Summer Palace; indeed it seems like he’s really just fascinated by Imperial China, and particularly of the grand palatial complexes that represented both the temporal power AND spiritual centrality of the Emperors. This yearning to steep himself in this history is such that our dude here wants to spend the night in the Summer Palace, just like he did in the Forbidden City, a very intimate connection to history, don’t you think? Our revere is interrupted, however, by the reminder that he (and us, by extension) are tourists here, and can’t just wander about and do as we please.

Our guy, unable to duck off and hide away in the Palace during the day, sneaks back in after hours and ends up swimming through the lake towards the boathouse he visited earlier. I think there’s some nice writing here, the way the lake is made into this mysterious, mythical place that our “hero” must cross:

We get great sensory writing here, the moonlight like glaring eyes, the fish and the lotus roots, a real “spell of the past” sort of thing…that is AGAIN broken by the reminder that there’s a thriving tourist industry here, that our guy first encountered these stories and images as a tourist being told these things. It’s a great little writerly trick, a very conscious and effective stylistic flourish that produces a marvelous mood; as weird fiction readers, we’re quite familiar with ruins and decay and the hoary tales of the past, but then to have them all contextualized as part of a modern tourist complex transforms the “mythic” landscape in a remarkable way – there’s even an explicit mention of the crass commodification of these cultural/historical/mythic tales, with anyone who can afford to being able to engage in what had previously been the sole privledge of royalty! It’s good stuff!

Our guy makes his way across the lake and up a canal towards the boathouse:

Good spectral writing in this section as our narrator investigates the forbidden boathouse. Invisible pigeons cooing overhead, the ancient boats (one half-sunk in the water), the sense of age and the weight of memory…it’s good environmental writing, real pleasurable. Burks, as mentioned above, was famous for his prolific output, but I do think you can tell when a writer is *into* what they’re writing, and this is such a clearly envisioned scene with such sharp emotional resonance that it’s impossible for me to think he was ONLY adding words up for money here. It’s honestly good stuff!

Anyway, our guy hangs out in the boathouse, musing upon history and the Emperors of China deeply and profoundly and, possibly, a little psychically? He feels like that, if he just puts his mind to it, he can summon up, in some misty, numinous way, a shadow of that glorious age…

Who could’ve foreseen such a weird turn of events!

Yes, our guy seems gripped by some vision…but is it an internal expression of his desire to imagine the past, or is it something more, something external to him? Regardless, and luckily blessed with the ability to understand Mandarin, he slips into one of the barges (the one still afloat) and watches a strange scene unfold before him!

First, and very nicely described in the prose, there wrecked barge rising from the water, mended and restored to its original glory. Then, a marvelous procession of people enter the boathouse:

A lot to unpack here – first off, the spectral figures are a stately procession of an Imperial Chinese household led, we can safely assume, by the shade of the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi herself. Alongside her is a powerfully built man armed with a beheading knife, an example of Chekov’s Executioner. But even MORE interesting is the way the narrators attempts to justify this scene transforms into a commentary of Ugly American Tourists. Perhaps these are but actors, hired by crass Americans to enact some kind of historical play for their delight and amusement.

It’s incredible how bitter this idea is expressed here, isn’t it? Our guy expects these Americans to appear any minute now “to pay their money, and watch, and laugh over” the show they paid for. “Tourists had no sentiment” is a remarkably condemning statement, and one apparently very strongly felt by the narrator. “The aura of heart-ache which shrouded this old place,” all the old “sorrows and tears” would mean nothing to a bunch of loud, rowdy Americans come to gawk and consume and generally disrespect history and the dead.

Our narrator is, presumably, also an American; only an American can have such sharply specific contempt for their countrymen, after all. It is interesting though that our guy here, of course, is also acting somewhat disrespectfully though, isn’t it? He swam the lake and broke into the boathouse after all – is the fact that he has reverence for the history (or so he claims) enough to absolve of, basically, doing exactly the same thing he’s cursing the hypothetical American tourists for doing?

It is a somewhat moot point however, because of course no tourists come in – this is not a reenactment at all. The Imperial entourage continues to pack into the boathouse, with the Empress and her favorites taking their place in the restored boat, while the rest of the crew piles into the boat in which our narrator is hiding (though they take no notice of him at all…). Then, in a very ghostly fashion, the chains slip from the boathouse doors, the gate opens, and the Imperial Barges sail once again the surface of Kun Ming lake.

There’s some very dreamlike writing here as they glide across the lake, whispers of mysterious conversation, the dilapidated ruins of the Summer Palace restored to their former glory, lights in windows and so forth. Our guy has clearly entered into another time, a spectral memory of China at its Imperial height, but even so he persists in thinking “any moment those crass American tourists will show up.” It’s a little funny, but perhaps the resilience of belief in the face of the mysterious is stronger than we can imagine.

Anyway, something happens which brings all this to a head for our narrator:

A man has been found within the grounds of the Summer Palace, and he’s in some serious trouble. The Empress, regal and terrible, steps from the barge to the shore, and confronts the man, who trembles before her. He’s beaten with bamboo rods, his blood mingling with the earth and staining the grass, and then, having confessed to his crime, the Empress orders him executed.

Now, before we go on, let’s take a moment to interrogate the usage of the offensive slur “coolie.” It’s a definitely racialized (and class-based) term, used to refer to laborers, particularly “unskilled” manual laborers, from south east Asia (generally India or China). The origins of the term go as far back as the 16th century, a Europeanized spelling of a Tamil word “kūli” which means “wages” or “hire.” It came into prominence and achieved its deeply racist connotation with the abolition of slavery by the British in the 1800s; needing a replacement for the vast labor needed to prop up the Empire and their colonial holdings, they took to hiring huge amounts of cheap workers and shipping them across the world from China or India to places like the Caribbean. These were, ostensibly, free people (mostly men) who had been contracted for their work, though in practice they were often little more than indentured servants, having signed contracts that basically enslaved them for a period of time. The labor trade was a major commercial enterprise of the era, both for the British and China, and is a hugely important part of the brutal exploitation of the age. It also carried over into the English language, and became a catch all term meant to convey a particular racial and class-based identity for the people being referred to. Interestingly, there is some relatively recent reclamation of the term, with working class heroes proudly proclaiming their identity as such in more recent movies and books. One of those things you have to be aware of and confront when reading old literature.

Anyway, our guy is troubled by what he sees – a brutal beating is one thing, but is seems clear that they’re going to kill this guy. He runs around trying to get them to stop, but he can’t actually interact with anybody – just like on the boat, they don’t seem able to see him, and when he tries to grab the Empress’s sleeve he simply can’t; it’s as if she’s incorporeal.

A grisly scene indeed!

Everybody, including our narrator, clambers back into the boats and continues their sailing around the lake, though it has become a decidedly weird experience for our guy.

The barges wheel about and make for the boathouse…and as they travel, everything seems to subtly begin to change:

Everything is returning to its ruined, dark, abandoned state as they travel the lake – whatever spell had restored the Summer Palace to its previous glory has vanished, apparently. There’s a wonderful line about the lights on the shore extinguishing as the boats sail by, a great and very spooky image, and when they arrive at the dock of the boat house there’s a shadow waiting for them, a kind of presence that seems to swallow up one by one the figures of the night’s haunting. When the shadow touches our guy, he feels a terrible coldness…and suddenly everything was as it was before in the boathouse; a barge sunk, everything dirty and dusty and abandoned.

He doesn’t swim back; he runs.

The coda to the story is a newspaper story that he comes across later:

And that’s THE END of “Chinese Processional” by Arthur Burks!

Now, as weird fiction, the ending is, admittedly, a little lackluster – the Empress returned to punish the guy who had tried to loot her tomb in the Summer Palace, simple supernatural vengeance story, pretty standard ghost fare. And the scene of the beheading is fine, though I wish it had been a bit more nightmarish, given the dreamlike quality of the prose that characterized the scenes on the lake.

But, all things considered, I like it. There’s good writing in here, like I said, and the fact that it’s a story set in China by a white guy and it’s not MORE racist or MORE “exotic” is actually pretty remarkable – Weird Tales, readers, writers, and editors alike, all LOVED a good ol’ “Mysterious Inscrutable Orient!” story, which can be quite rough going these days. But the tone that the author takes here is, shockingly, respectful, at least of the Imperial past of China. And the way he attacks tourism, and AMERICAN tourists at that, is very interesting and, honestly, fairly atypical for the era. Just goes to show you that there’s often SOMETHING interesting in the stories that showed up in these magazines!