Moorevember is the cruelest month, at least this time around, so our posts have been a bit thin on the ground. Nonetheless, here we are on the eve of Thanksgiving to celebrate another great bit o’ pulp, this time a semi-silly story full about labor agitation, class struggle, and gnomes, by Henry Kuttner (and C.L. Moore – we’ll talk about the authorship below). It’s “A Gnome There Was” in the October 1941 issue of Unknown Worlds!

You might remember this issue, if you’ve been reading along – we’ve actually flipped through these very same pages when we talked about Fritz Leiber’s killer story “Smoke Ghost” last month. It’s an interesting pairing for a single issue of the magazine, given the subject matter; both stories are broadly concerned with industrial modernity and capitalist oppression, something on the minds of a lot of folks back in the late 30s-early 40s (twas ever thus…).

Anyway, since we’ve already been over the ToC and all that, let’s dive right in!

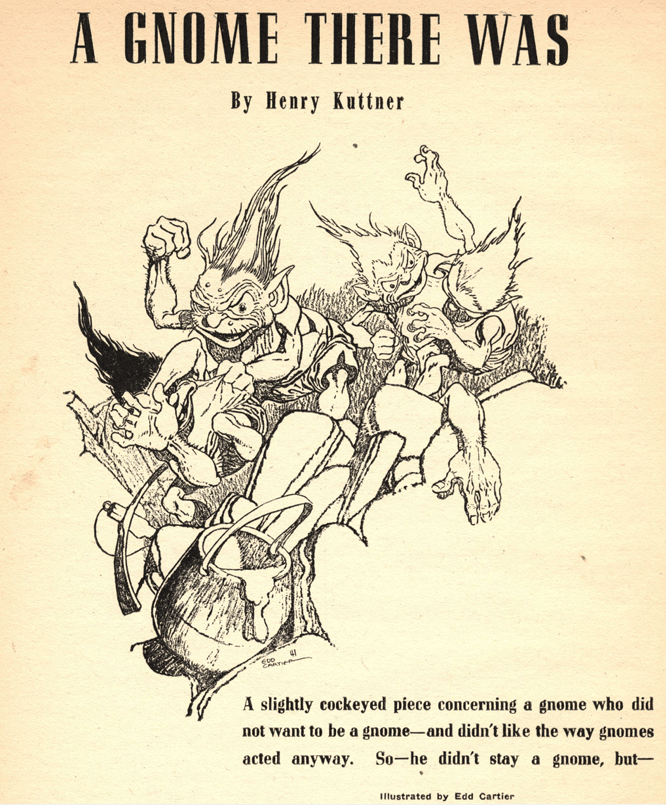

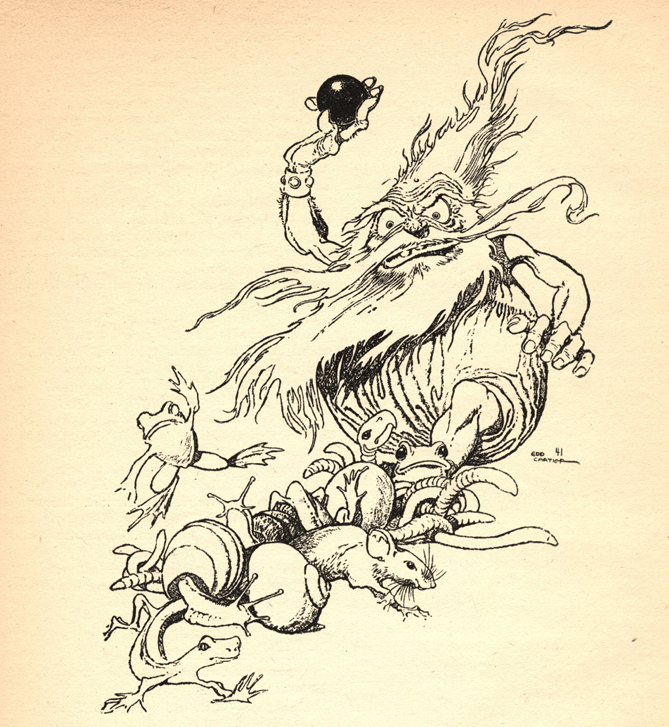

Great illustration on the title page by Edd Cartier, perfect little gnomish guys with great expressions and proportions. no notes! Cartier does some good illos in this one, and you really gotta appreciate Unknown Worlds art dept, just some top-notch talent all around.

First off, let’s talk authorship – right there on the title page, and on the ToC too, this story is attributed to Henry Kuttner solely and individually. The complication comes later, in 1950, when this story was included in a collection, “A Gnome There Was and Other Tales of Science Fiction and Fantasy” by Lewis Padgett.

The Padgett name, we know, was one of several noms de plume that Kuttner and Moore published under. Now, I’ve not read that collection – it’s entirely possible that Moore helped Kuttner revise the story in the intervening years, although that’s pure conjecture. More parsimoniously, I’ll just go with the idea that, given their incredibly close writing partnership and their self-admitted inability to tell who wrote what, this story was a Kuttner/Moore joint production that they just published under his name solely, for whatever reason.

Last time in discussing their collabs, I mentioned that I felt that, more often than not, you could spot the “Moore” parts and the “Kuttner” parts pretty easily; based on my gut-feelings-based-approach, I do think that there is a LOT of Kuttner in this one, particularly in the more slap-sticky bits. That being said, I think there’s plenty of (admittedly vibes-based) evidence for Moore in here too – the sense of menace, the alien-ness of the gnomic world, the oddly libidinal violence, and the sharper-edged social commentary are all just extremely Moore-esque, you know what I mean? But see for yourself and let me know what you think!

A scathing indictment right off the bat, of our main character specifically and a certain flavor of “activist” more generally, and damn if Kuttner and Moore don’t go for the throat right away! If you’ve ever spent any time inactivist spaces, you’ve definitely encountered someone like Tim Crockett – an entitled know-it-all bleeding heart with nothing but bottomless contempt for those they, ostensibly, are supposed to be helping. These sorts certainly know better than the workers what is needed and how to get it, and are bravely and selflessly willing to help these poor benighted souls out of the pit of their own oppression.

There’s a lot of very heavy-handed stuff in these first paragraphs, but there’s also a very nice, subtle dig in there too – the part where it’s mentioned that Crockett, a great giver of speeches and writer of articles, has chosen not to use his connections to get into law, a place where someone with real convictions and a drive could actually learn some stuff and do some good. It’s a good, sharp bit, and sets up Crockett right away a kind of feckless, spineless worm, more interested in the social capital gained from activism than from activism itself.

The mention of the “Kallikaks” deserves some explication, as it’s a fairly obscure but important bit of history. In the early 20th century, as the modern sciences of heredity and psychology were juuuuust starting to be teased out and explored, a fellow by the name of Henry Goddard published a seminal book titled The Kallikak Family: A Study in the Heredity of Feeble-Mindedness. Goddard was a eugenicist, like a great many educated people at the time, and ran a hospital for “feeble-minded” people. One of his “patients” there was a woman named Deborah Kallikak, and Goddard claimed to have discovered a clear-cut genealogy in her family basically proving the tenets of eugenics and hereditary hygiene. Basically, according to Goddard’s book, the Kallikak family could be divided into two halves, one “good” and “healthy” and the other cursed with disease and “feeble-mindedness,” traced back to a Revolutionary War era grandsire who had a “dalliance” with a bar maid while returning home one night. Thus, two branches of the Kallikak’s sprung from his loins, the upright and healthy side from his lawful marriage and a tainted lineage from his impure relations with a social and moral inferior. It’s all bullshit, of course, with copious amounts of lies and fabrications from Goddard (explored and explained in Gould’s great book The Mismeasure of Man, which everyone should read immediately). But at the time, and well in the 50s and 60s, Goddard was one of the titans of eugenics in America, and his “study” of the inheritance of the Kallikaks featured in all sorts of textbooks and papers and monographs.

Now, the use of “Kallikak” here is basically just saying that our character Crockett, a self-deluded meddler, probably believed that the workers he was “helping” were congenitally “lower class” and “feeble-minded” and, therefore, incapable of organizing themselves. Moore and Kuttner, of course, were interested in questions of heredity and the family; check out our discussion of their “When the Bough Breaks” from earlier in the year to read about all that. While I’m certainly not calling Moore and Kuttner eugenicists, I think sometimes we have a hard time recognizing just how ingrained into the mainstream those ideas were (and are still). The idea of genetic hygiene, of bloodlines mingling and diluting and passing on undesirable traits, was simply taken for granted – I mean, consider the whole of gothic literature and its preoccupation with congenital madness, for instance. The eugenic idea that, through careful and selective “hygiene” (i.e., choices of breeding) the human species could be “improved” was something that, likewise, was taken for granted at the time, and Moore and Kuttner were embedded in that milieu, same as everyone else.

A long digression, but that’s to be expected here, I reckon! Anyway, on with it!

We learn that Crockett has been jetting around, trying to infiltrate various industries to get the scoop on labor oppression, with a healthy dash of tragedy tourism in there too. He’s currently snuck into a coal mine in Pennsylvania where he’s disguised himself as a miner and descended deep into the earth. However, while he’s bumbling around and generally making a nuisance of himself, he accidently stumbles into a disused shaft that gets demolished, trapping him!

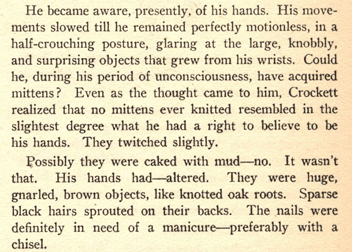

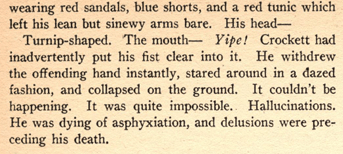

Waking after who-knows-how-long, Crockett slowly gets his bearings – he thinks he sees some kind of weird figure, but it vanishes and he decides that he must’ve been hallucinating. Then he starts to wonder how the hell he’s seeing anything anyway (radium, he decides, stupidly) and then begins to panic! Digging madly, he suddenly notices his hands:

Shocked, he continues the self-examination:

It would appear that Crockett has turned into a Weird Little Guy! His assumption, that his dying brain is causing him to hallucinate, would be a good one, if he weren’t in a pulp science fantasy story. Because, of course, the reality is that he’s been transformed into a Gnome, which he soon comes to realize when he hears a voice talking to him.

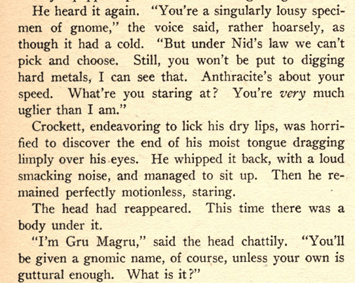

Crockett gets lifted up and hustled on his way, escorted by Gru Magru, who somewhat condescendingly explains to Crockett what’s happening:

It’s breezy and light, but a lot of fun – I like that kind of straight-forward fantasy stuff too, just enough exposition to get you situated and with some vague gestures towards a larger world to keep you interested, solid fantasy writing in my opinion.

Anyway, ol Gru Magru is hurrying Crockett along because he’s heard a fight has started, and he desperately wants to join it. This is a fun and weird bit of the story, because it turns out the fight is between gnomes, and it’s basically a form of recreation – we learn later that its the one unsanctioned non-work activity that they’re allowed, and they relish it. In fact, it’s almost a sensual experience for them, apparently – walloping and clobbering one another is a real, vital activity for the gnomes, and while it’s played for laughs there’s also a kind of deep strangeness going on here, where the gnomes, basically slaves to their emperor, can only connect with one another via violence. There’s a lot going on in there, I think!

In the brawl Crockett meets a girl gnome, Brockle Bhun, and learns about the important place the Brawl has in gnomish society. Then, the fight ended, Gru Magru grabs Crockett and drags him off to meet the Emperor, who likes to meet the new gnomes before they get put to work. In the throne room, they meet a gnomish servant of the emperor, who explains to Crockett (and us) that the emperor is basically a lazy indolent slug who luxuriates in mud baths all day – your standard senior managment, really, a characterization that is underscored when Crockett meets him. At first, he seems an easy-going sort, jovial even, getting Crockett oriented and admonishing him to work hard, but he finds a worm in his mud bath he becomes a roaring, bloviating, insulting bully. Basically, he’s a CEO.

Crockett is put on anthracite mining detail (and he’s told NOT to eat it, just mine it), where he again meets Brockle Bhun, a troublemaker who DOES like to eat the anthracite. More good art around this part, with a gnome hard at work:

While working, his new pal Brockle Bhun fills him in on life as a gnome – everybody works for the emperor, who rules through his powerful magic. That’s it. You work, you sleep, you work some more, there’s an official break after hour ten although you can fight as much as you want. A grim life of toil, although it’s taken as the simple, gospel truth. In other words, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of mining, for a gnome.

Crockett, of course, finds the work difficult and exhausting, and so he begins to scheme a way out of it. If the emperor is a magician, perhaps he could transform Crockett back into a human and set him free? But how to convince him? The answer, of course, is a work strike.

Now, like a lot of this story, this solution is played for laughs, although I think it’s more than just a kind of shaggy-dog yuk-it-up sort of tale. Crockett was a labor organizer (of sorts…), so his mind turning in that direction is consistent with his character. Also keeping with his particular history is that he’s doing it solely to help himself. We know he’s actually kind of a snake and a parasite, unconcerned with the actual plight of the worker, so his plan for a strike that would force the emperor to negotiate is all in service of helping HIM, rather than the workers. Consistently satirical, a hallmark of Moore and Kuttner.

Anyway, that night there’s a secret planning committee meeting, where Crockett lays out the theoretical underpinnings of the labor strike and what they could get out of it. The other gnomes seem kind of half-hearted about it, until Crockett lies and says that the Emperor is planning on outlawing fighting; that makes them sit-up alright, since fighting is a cherished and beloved and, perhaps even vital, pastime for all gnomes. It’s that lie that convinces them to join in and agree to the strike. It’ll be dangerous, though:

The cockatrice eggs are the basis of the Emperor’s power – with them he can transform gnomes into all sorts of nasty things, including humans. Obviously, Crockett is very interested in the red human-transforming eggs. Everybody agrees to meet in the council chamber and declare a strike, and then the meeting devolves into a brawl.

Afterwards, and presumably in bed, Crockett engages in a bit of introspection:

An interesting bit of musing, on his part, and one that we, as readers, have to wrassle with. Is this alluding to the idea that, perhaps, there is a natural order to the universe, with some people being meant to be workers and others, naturally, bosses? Maybe Crockett’s dissatisfaction with his gnomish life is a left-over bit of his humanity that, given time, will be worn away? It seems possible:

Is Crockett simply struggling against being a worker, something that he secretly desires and, maybe, needs? There’re some complicating (and, honestly, reactionary) readings that could be made from this, although of course they are coming from Crockett, a character that we know is kinda dumb and untrustworthy. It’s a fun, complicated text, the sort of thing you expect from C.L. Moore (and Kuttner, when he’s working with her).

Anyway, after an exhausting day of work, Crockett and the rest of the gnomes assemble in the council chamber. The emperor barrels in, and Crockett declares the strike:

Crockett, laboring under the misapprehension that the cockatrice eggs are stored somewhere, tries to encourage his gnomish comrades to interpose themselves between the emperor and any doors that might lead to his stash. Gru Magru disabuses him of this notion – the emperor simply pulls the eggs out the ether, a kind of key tactical point that would’ve been nice to know about ahead of time.

The Mother of All Brawls erupts in the cavern, with all prole gnomes trying to wallop the emperor, who is just as scrappy as any of them, even without his magical weapons. Crockett tries to get everybody to sit down and negotiate, but the die has been cast and its a regular donnybrook in the council chamber. Finally, the emperor starts chuckin’ cockatrice eggs!

There’s some fun writing here – the image of this king hurling crystals into gnomes, and then the gnomes getting instantly turned into weird little critters by them, is a lot of fun. We get a good scene where some gnomes, caught on the edge of an explosion, are only partially transformed; one gets a mole head, another a worm’s lower half, and yet another gets turning into something unrecognizable, causing Crockett to realize that the cockatrice eggs aren’t restricted to the zoology he knows alone. It’s fun, and there’s a great illustration:

There’s also a fun bit where the emperor pulls out a red cockatrice egg; that, according to what Crockett has heard, turns gnomes into humans, as foul a fate as can be imagined. The emperor agrees apparently, because he thinks twice about throwing it and then, very carefully, sets it down behind him, rather than using it. Crockett, seeing his chance, darts forward and grabs it! Maybe he’s got his ticket back to humanity? Looking back on last time, Crockett sees a total bedlam in the council chamber:

Crockett wonders where it went wrong as he flees. Podrang should’ve negotiated, should’ve sat down and, recognizing that it was in his best interest, agreed to a compromise between himself and his workers. It’s an interesting bit of commentary, and you can read it how you like – maybe it’s a scathing indictment of Crockett and an organized labor movement that cannot see beyond its immediate needs and its relationship to management? Or maybe it’s saying that the bosses, and the system they serve, is not rational at all, that it would destroy itself and everything else rather than cede any power or control? At the very least, it’s clear that Crockett has misjudged the power of the gnomish proletariat and the determination of the gnomish emperor, because the latter has squashed the former and is now chasing after him! Crockett sprints through the earth, spots daylight, and runs hard, but he realizes that the emperor is RIGHT behind him – he won’t make it! So, he turns, and lifts the red egg over his head!

He wakes eventually, and is pleased to realize that he’s seeing the sunlight not as a dazzling and poisonous glare, but as a pleasant and healthful glow, like a human would. The emperor pulls himself out of the rubble, takes a look, and then flees back into the earth with a scream! Of course, Crockett remembers, gnomes are afraid of humans, that must be it. He’s free! He’s escaped!

And that’s the end of the IWW pamphlet “There was a Gnome” by Henry Kuttner (and C.L. Moore)!

There’re two ways you can read the ending, I guess. One is that he’s a weird mixed up monster, right? That the half-dozen or so spheres all interacted and left him some kind of chimera. The other interpretation, and the one that I prefer, is that the red one DID work first, but it’s just that red doesn’t make humans, but rather something else alien and horrible (like the thing he saw in the council chamber). Doesn’t really matter, of course – Crockett comes out, thinks he’s escaped, but he’s actually been transformed into something horrible and scary and weird.

It’s a fun and silly fantasy story, and even if that ISN’T your thing I think you can agree that it’s written well; the pace is brisk, there’s plenty of weirdness, and the gnome world and lifestyle is presented well and interestingly, without any superfluous nonsense and a lot of solid, good strangeness. The labor organizing aspect of it is interesting – it’s certainly making fun of that era of kinda dumb, feckless activists, people obviously more loyal to the aesthetics of organization than organization itself. There’s ambiguity there, of course – is Crockett meant to be a stand in for a particular kind of labor aristocrat organizer, or is he meant to indict the whole movement? Are the workers/gnomes actually happier in there “place,” or are they blinded by habituation to their own exploitation? It’s an interesting story because it doesn’t really come down on one side or the other, but I feel like the fact that it engages with these ideas and makes us think about them is, actually, a much better purpose for fiction (no one wants a didactic story, you know what I mean?)

It’s interesting that this issue of Unknown Worlds had “Smoke Ghost” and this story in it together – they both come off as pretty radical, honestly. “Smoke Ghost” of course is a bit harder edged; it explicitly evokes a decaying world prey to monsters as the direct result of capitalism and its handmaiden, fascism. But this one is clearly capturing a moment too. Obviously the depression had seen a lot of labor organizing, but with the build up to world war II (raging in europe at the time, though America wouldn’t join in until December of the year) there had been a substantial bit of tension in the country’s industrial base; there had been a huge steel worker strike earlier in the year, and the idea of social justice and unrest had been bubbling away. In that light, it’s interesting to see the ways pulp fiction reflected these ideas and concerns, and I think “There was a Gnome” makes for not only a fun story, but also an interesting historical document.

Anyway, that’s it for now! Hope ya’ll have a good holiday, if you’re in the states, or a good thursday if you’re not! Take ‘er easy, and see ya’ll next time!