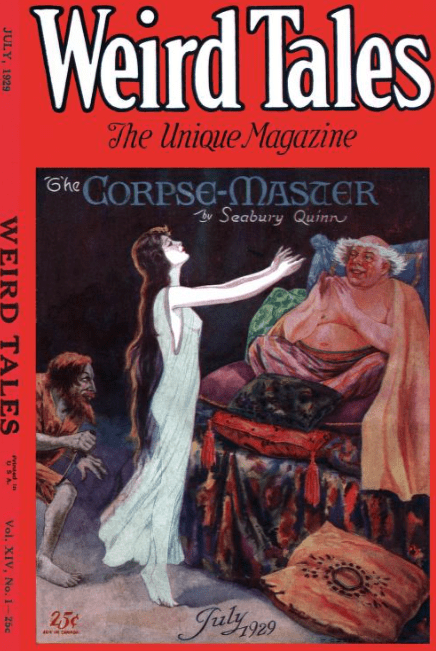

Hallowe’en eve, so why not take a break from building your wicker men or hanging thorny wreaths from the old Druid Oak to read some more pulp weird fic! And it’s a fun, haunting one today: “The Wishing-Well” by E.F. Benson, from the July 1929 issue of Weird Tales!

Looking back at the previous Hallowe’en flavored Pulp Strainers this time around, it kind of seems like I’ve been on a Classic Monsters kick, for the most part. Ghosts and Vampires and scary Subway Ghouls; it’s been a regular mash, or perhaps bash, around here. And who am I to buck against the momentum we’ve been building up? So, having reflected on the previous stories, I decided I wanted to do a witchy one today, and after careful consideration (’cause there’s a LOT of ’em out there!) I landed on this story by E.F. Benson, a particular favorite story from a particularly good writer.

Now, I’m a weird fiction guy – I love it strange, I love it confusing, I love the peek through the crack in reality that the genre strives for. So what the heck are we doin’ focusing on TradMonsters like ghosts and witches, you may be asking? I mean, didn’t Lovecraft chuck all the tired old cliches out the window? After all, as the Old Gent said, Weird fiction is “more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule.” So where do these matinee monsters fit in?

Well, Lovecraft actually kind of answers that in the very next sentence in his “Supernatural Horror in Literature” essay: successful weird fiction is characterized by a “certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces.” In other words, the problem isn’t yer wolfmans and draculas per se…it’s the hackneyed and trite conventions around them that turn a horror story into a dull, rote recitation of banal familiarity. Even the most overused horror mook has SOME kind of vein of weirdness that can be mined – take Lovecraft’s own “The Dreams in the Witch House,” complete with a cackling crone and satanic pacts and sabbaths, and you’ll see that it is possible to take a stock Halloween character and turn them into something interesting and strange and truly weird. And I think that’s the case in today’s story too, which takes a very thoughtful and modern approach to witchcraft.

Which is par for the course for our author today. E.F. Benson was a writer not only of spook-em-ups, but of “society” literature, essays, and biographies as well – he was extremely prolific, with hundreds of short stories to this name. He was also gay, a fact that is relevant when reading his work, which often have either subtextual gay relationships in them or, more broadly, deal with themes of romantic and social alienation. There’re a lot of outsiders in his stories, particularly in his ghost/horror/weird stories, as we’ll see shortly.

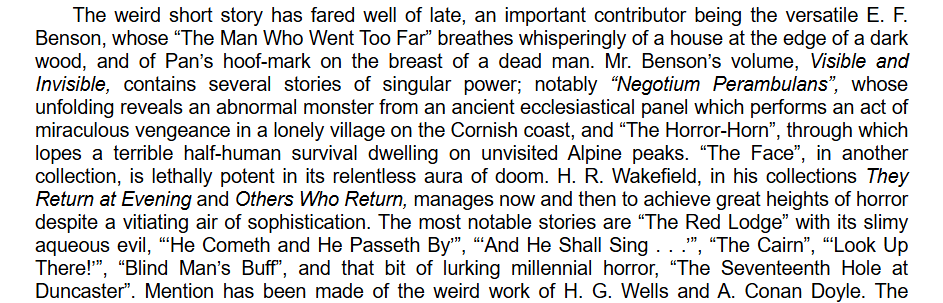

While he’s fairly well represented in anthologies, particularly those published in England, he’s probably most well known today among weird fictioneers because Lovecraft singled him out for specific praise in his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature:”

That’s high praise, and well deserved, I think; Benson could, when he wanted to, get pretty weird, occasionally producing some truly otherworldly and alien monsters. The weird Hell Slug in “Negotium Perambulans” would be a worthy addition to the mythos, I’ve always said (and it seems like it was a huge influence on Brian Lumley, who had a darkness generating extradimensional slug in some of his Titus Crow stories).

But, even when ol’ Benson WASN’T going all cosmic, I think he still had a streak of the Outside about him, you know? Even in his most conventional ghost story, there’s always a hint that there were deep shadows both within people and outside in the wider world, and I think that’s what I like about the story we’re going to talk about today.

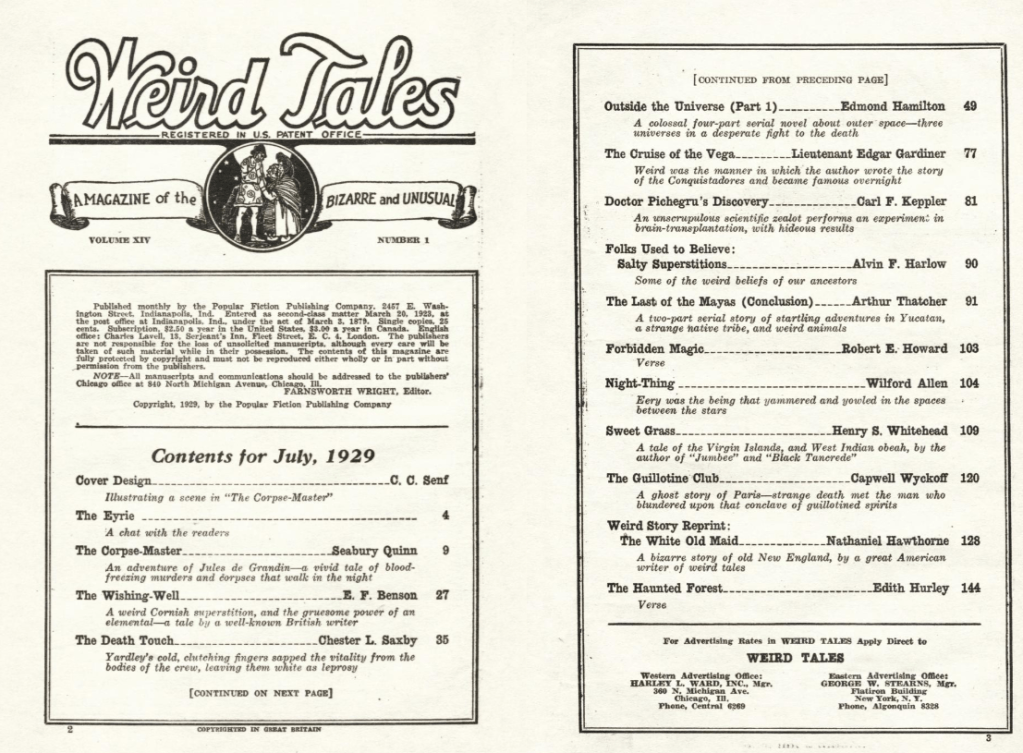

But first, lets take a peep at the cover and the ToC!

An excellent Senf this time, very weird and menacing. Love the corpse-white lady contrasted with the riot of colors, and the sneaky lil’ feller on the left, leering and with dagger drawn, is fun – it’s all very lurid and decadent, a perfect Weird Tales cover in my opinion. As for the ToC:

Quinn and Whitehead are probably the Big Names on here if you were a fan in ’29 reading the magazine – both of them were popular, though they can be tough reading these days (Whitehead because of the uncomfortable paternalism and exoticism of his “voodoo tales,” Quinn because the Jules de Grandin stories are just not that good). There are some interesting oddities in here, though! Hamilton writing a “planet story,” the sort of thing that would eventually get shifted over to the science fiction pulps once they get a little more firmly established. There’s the poems, including some vintage REH, but there’s also a very strange little story by Lt. Edgar Gardiner, “The Cruise of the Vega,” which is an enjoyable little bit of metafictive fun, ostensibly an essay written by Gardiner about his hugely lucrative and wildly popular novel “The Cruise of the Vega” (which isn’t real, of course) and the REAL story of how he came by the tale. It’s fun, and speaks both the inventiveness of writers at the time and the fact that the genre has always been playful about itself and the writing profession.

But enough! On to the story!!

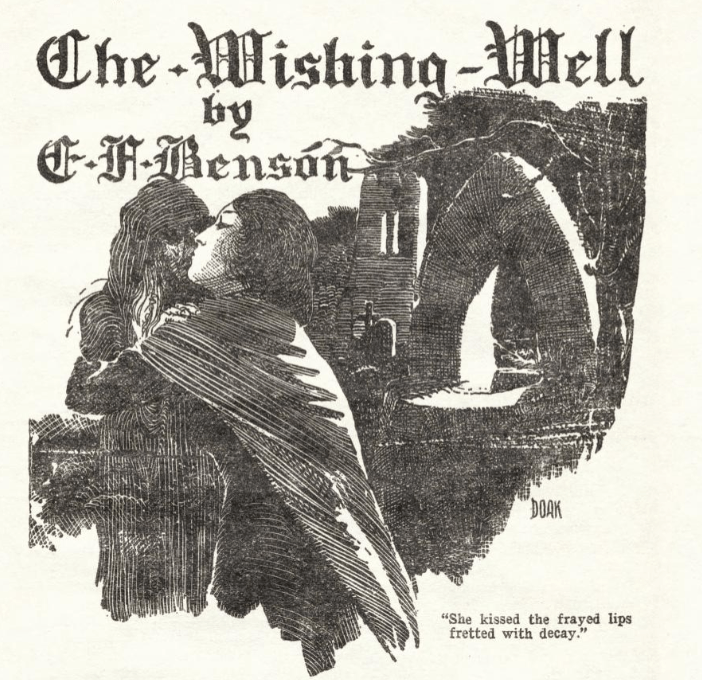

A great title illustration by the inimitable Hugh “Doak” Rankin! It’s a great, atmospheric piece, beautiful shadows and light, and the slightly translucent specter getting smooched, coupled with the creepy line from the story, is basically perfect. Points also for not giving anything away in the story! Rankin was one of the big interior illustrators, and did important work on Lovecraft and Howard stories, among others, so it’s fun to see him here too!

Our story opens with a very Dunwich-ian geographic summary, situating us on the Cornish Moors and in the tiny, out-of-the-way, remote little village of St. Gervase. People don’t come to the town, and those in the town seldom leave it. It’s mostly cut off from the world, and the people of St. Gervase like it that way:

Yes indeed, it seems there was, and perhaps still are, followers of The Old Ways in town here, hedge witches and wise women, part of a long matrilineal tradition of secret knowledge. Of course, every light casts its shadow, and for all the healing and wisdom, there’s also a darker cast to these powers, a tradition of affliction and evil that is, apparently spoken of only in one house in St. Gervase. And what house is that?

That’s right, St. Gervase has a very M.R. Jamesean vicar, a bookish and independently wealthy scholar who, in between some light preaching and bake sales, has become an academic authority on magic and folklore and witchcraft.

What’s fun about this character is that, while he’s this vaunted authority on witches who lives in a town with a vibrant and apparently thriving witch scene, he’s curiously removed from the living tradition in St. Gervase. He knows of the history of the town, and even apparently has some reports from locals on older traditions, but (as we’ll see) he is one of those academically informed types who can’t seem to see the forest for the trees. His patriarchal (and paternalistic) view of the world has cut him off from the cultural underground that is, quite literally, all around him.

But you know who IS making use of all of the Good Reverend’s research? His spinster daughter (she’s 40, and unmarried) and unpaid research assistant, Judith!

There’s some fun writing, just above this except, where Benson is taking pains to really situate Judith in the Cornish landscape of St. Gervase. He’s also interested in taking pains to explicate her complicated relationship to the town and the people and her own life – she has been isolated “from her own class” and, therefore, never had any serious prospects for marriage or a life outside of her Father’s home, and while that has (and does) engender some bitterness in her, for all that she IS in love with the town and the land and the strange undercurrents of older, matriarchal traditions and knowledge (as we’ll see).

The bitterness in Judith might be stronger than even she realizes, however – without putting too fine a point on it, Benson takes some pains to really show how Judith is absolutely fascinated by the darker, more retributive side of the magical lore that her old dad is researching. And now, down through the months and months, she was taking dictation from him on his researches about wishing-wells, and in particular, the famous Well of St. Gervase!

Rev. Euster’s helpfully expository declamations tell us that the best and most famous of these strange, satanic wells is in St. Gervase and that its power is still respected, though of course no one in town actually uses it these days. With regards to this, however, Judith knows better:

The shift from the landscape to the Reverend and then, finally, to his daughter Judith as the main character of the story is a neat little trick, a very fun way to sink the reader deeper and deeper into the story, as well as providing a sense of nice, comfortable disorientation, which of course is one of the pleasurable aspects of weird fiction. The uncertainty of the direction of the story, even as we begin to get little glimmers of familiar witchy-ness here and there, is an extremely masterful touch, part of Benson’s strength as a writer.

Judith, her head full of her father’s research of wishing-wells, heads on out into the countryside to visit a particular acquaintance, a Mrs. Penarth, who we quickly learn is something of a wise woman, indeed may have been The Wise Woman in St. Gervase, because in addition to her fame as a healer, also seems to have been the only person in town not afraid of Old Sally Trenair, the spooky witch we were introduced to earlier. In fact:

We also learn that Mrs. Penarth has a strapping son named Steven who has just returned from overseas. Judith remembers him as a boy, and is interested to see the kind of man he’s become, though the main reason for her visit is to pick the brain of Mrs. Penarth about the scholarly materials she’s been learning about at her father’s side.

On her walk there, Benson gives us some good description of Judith who, for lack of a better word, sounds hot as hell:

I call out this particular bit of description for a couple of reasons. First, it’s interesting to see Benson making sure we’re not thinking of Judith as mousy or shabby or a shrinking violet – she’s tall, she’s robust, she’s vital and active and sharp. That’s important to the story because otherwise, if she were this drab little thing, the tale becomes rather conventional and uninteresting. Instead, there’s a real sense of Judith as a forceful personality with an, if not imposing, then at least vibrant presence. Also interesting is the bit about the eyes – the slight inward turning as both a physical AND mental aspect, and not as a disfigurement, but rather as simply a part of who Judith is, warts and all.

The second reason I bring it up is because, as a writer myself, I generally eschew descriptions of characters (except for my villains, who are almost uniformly towheaded aryans) because as a reader I usually find them boring and pointless. Here’s a good example of a description used well, though – Benson is DOING something in the story with Judith’s physical description, in the same way as he was DOING something with the shift from the landscape of St. Gervase to the Reverend to, finally, Judith. It’s a very neat writerly trick, and speaks to Benson’s mastery.

Anyway, Judith arrives at the Penarth’s and find Mrs. Penarth knitting (a perfectly witchy activity, putting together the threads of fate and all) on her front steps.

Good bit of Cornish cadence, I reckon, and an immediate sense that Mrs. Penarth is as wily and cunning as we’ve been lead to believe – the bit about being hatless and making friends of the sun and wind is just perfect. And then, to really hammer home Judith’s somewhat protean nature (and her need to belong), we get the next bit:

It’s already been mentioned that Judith is of a different class than the native St. Gervasers; it’s why she never married, after all, and you can bet that the Ol’ Rev never slips into a Cornish accent around the house.

Judith’s mentioning of the death of Old Sally Trenair brings up a sly remark from Mrs. Penarth:

Perfect, perfect, perfect; just such a smooth and unobtrusive way to paint Mrs. Penarth as knowing certain things and secrets, and seeing in Judith a similar yearning. It’s really great. And, of course, it also efficiently serves the interests of the story, for we get another bit of exposition about the Well, though unlike the removed and scholarly musing of her father, Mrs. Penarth knows of which she speaks:

Mrs. Penarth’s quick-n-dirty user’s guide to wishing-wells is interrupted by the arrival of Steven, and goddamn if he didn’t grow up hunky as hell. Judith is immediately smitten with this big blonde slab of corned beef. Between her learning some pretty startling things about the Wishing-Well in town and meeting Steven Penarth, her brain is all a-bubblin’ like a witch’s cauldron.

After an evening of dictation, she takes a nighttime walk through the village, the air sultry and the sky overcast. She gets a little thrill when she catches sight of Steven walking into town. When he’s out of sight, she turns into the churchyard where the wishing-well yawns in the dark. Beyond it, she catches sight of Sally Trenair’s freshly filled grave:

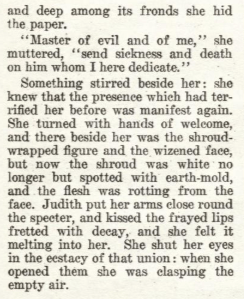

The spirit of the old witch IS there, “friendly and sisterly and altogether evil.” I mean, how is that for a turn of phrase, huh? Helluva writer, ol E.F. Benson, and the way he’s building this atmosphere of mystery and deep, earthy magic, it’s just really incredible, isn’t it? Judith drinks from the occult well, and is granted a glimpse of the ghost of Sally:

Judith’s fear seems to banish the ghost, and the horror of her vision of the dead haunts her for a few days – she seems to be both annoyed that she, perhaps, squandered her chance to commune with something powerful, and also a bit trepidatious about her glimpse beyond the veil.

She throws herself into the banalities of day to day life in order to find some respite, and in particular begins to make subtle efforts to come into contact with Steven Penarth, making sure she’s out gardening when he delivers milk, for instance. As music director of her father’s church choir she starts singling out Steven for praise, and also seems to have taken a jealous dislike to a pretty young villager by the name of Nance. Judith takes to calling on the Penarth farm more and more, no more merely seeking Mrs. Penarth’s witchy wisdom but also hoping to catch Steven at home. It’s clear that Judith thinks she’s being very clever and discrete, but Benson makes sure we get the hint with a phrase rich with double meaning: “In a hundred infinitesimal ways she betrayed herself.” Because not only is she being insanely obvious with her infatuation, but she is also, step by step, moving towards Doing Something about it:

Judith makes her way to the churchyard and the Well, but just as she arrives she comes across something Fateful:

Oof, right? Sad stuff, and embarrassing as hell too, to find out that all your clever dissembling was seen through immediately. The part about Mrs. Penarth laughing at her is particularly bitter, isn’t it? And then, to hear Steven propose marriage to Nance after all that? Well, it’s a grim moment for poor ol’ Judith.

Grim and spooky stuff! Judith takes the slip of paper to the churchyard and the wishing-well, and feels the tide of her power rising:

I mean, what a great bit of writing, murky and grim and just freighted with occult power, isn’t it? The ghost that appears before her now is a rotting, decayed thing, appropriate for the use to which Judith plans to put its power. And how about that smooch that seals the deal? Honestly an incredible image!

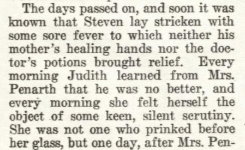

Say what you will about the dark powers of the earth, but they fuckin’ deliver, man! Right away, next morning, it’s not Steven who delivers the fresh produce to the vicarage, but his mother, Mrs. Penarth. Seems poor lil Stevey is feeling a bit under the weather, real shame that, what with his marriage to Nance coming up and all.

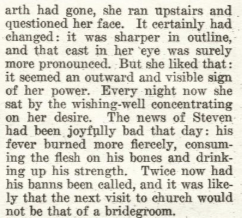

Judith had leaned into her Evil Sorceress phase, but we the reader see the fatal flaw in her plan – as we learned, there were Two witches in town, and the stronger of them is not only still around, but also the mother of Judith’s victim. Oh, and also, SHE WAS THE ONE WHO TAUGHT YOU ABOUT THE POWER OF THE WELL!!! So, of course, as a canny and wise witch, Mrs. Penarth lies in wait in the churchyard, to see if someone hasn’t been screwing around with forces they can’t comprehend.

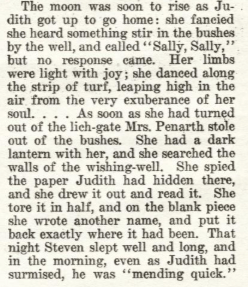

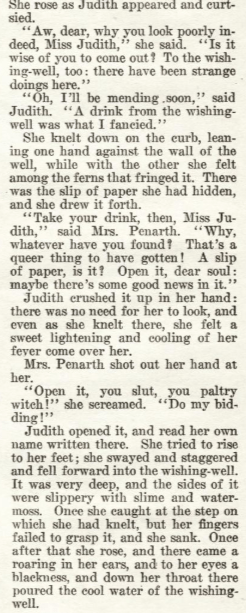

Steven is almost immediately better, while Judith, with similar alacrity, starts wasting away. She feels the dark power that had filled her being drained away too, taking her life with it. Even the ghost of Old Sally is taken from her, leaving her weak and alone and dying. Steven is back to delivering the milk, and asking after Judith’s health on behalf of his mother. Judith doesn’t understand what’s happening – has she missed some important step in the spell, or failed to fulfil some expected action, and that is why she is now being afflicted by the curse she had laid on Steven. Only one thing for it – gotta check on the well, and the slip of paper she had put there. Stumblingly, she makes her way to well, and when she gets there, she finds Mrs. Penarth!

And that’s the end of “The Wishing-Well” by E.F. Benson!

Potent stuff, huh? Mrs. Penarth’s vengeance is swift and terrible, something poor ol’ Judith might’ve expected given the well known history between her and Ol’ Sally. And while sure, she DID try to kill someone through dark sorcery, you can’t help but feel a little bad about Judith’s end, you know? The solitude and longing and shame of her life – Benson makes us see all that, makes it a deep part of Judith’s being, and there’s a real pitiful quality to it. Particularly so, now that I think about it, because as was established at the beginning of the story, witchcraft was a passed down mother to daughter, a tradition of secret knowledge held by women; Mrs. Penarth had a son, though, so to whom was she expecting to pass on the wisdom and power of the strongest witch in St. Gervase? Sure does seem like she was maybe sounding out poor Judith for the role, doesn’t it, the way she was quick to spot something intriguing in her questioning and the way her mind worked, as well as her willingness to share the lore and traditions with her. It kind of explains her obvious anger at Judith – not only has she attacked her son, but she also has betrayed her, trying to use the little knowledge she had been given in such an irresponsible and dangerous way.

The view of witchcraft in fiction today is almost uniformly a feminist one, and there’s a strong thread of that in this story from 1929: witchcraft as a tradition of women of course, but also in the way Judith, though seemingly content, has been denied a full life by the patriarchal class-based rigidity of society. Furthermore, the breakdown of the relationship between Judith and Mrs. Penarth, one that would have had full consummation in the sharing of witchy tradition, is brought about by the advent of a conventional marriage, with Judith trying to corrupt it and Mrs. Penarth trying to preserve it.

This feminist reading of witchcraft is one taken up by a lot of modern “folk horror” (a term I’m not enamored with, but oh well), which makes for an interesting tension because, of course, the other major axis in folk horror is almost always something along the line of Deep Tradition. That kind of battle between empowerment and traditional gender roles makes for some unique frisson in works of that sort, and I think that’s something at work here – Judith’s desire for liberation undone by her rage at the most conventional expression of heteronormativity.

Benson’s interest in women and their role in society is well documented; his novel “Dodo” (and its sequels) is all about an Edwardian proto-flapper spitfire and the ways one can twist and wiggle through society’s hoops to get what one wants. There is some biographical aspect to this, I reckon; as mentioned above, Benson was gay, but ALSO of a social and economic class that, while not necessarily allowing him to live openly, did give him a certain freedom to quietly and politely live his life without being arrested. In other words, he wasn’t exactly closeted – it was more of a don’t ask, don’t tell kind of gentlemen’s agreement where everybody (within that stratum of society) knew he was gay but had the good taste not to mention it, and he reciprocated by not wearing it on his sleeve.

This kind of fluidity and ambiguity is something that Benson explores in a lot of his fiction, and it makes this particular story an interesting one – he’s really captured something in Judith’s lonely outsider status, a woman seemingly resigned to her life rather than liberated by it. There’s also a simple parable about the destructive nature of both sexual inexperience and infatuation here – in a lot of ways, Judith is an incel, isn’t she? She’s been forced (by society) into spinsterhood, and then when her affection isn’t reciprocated, she fuckin’ tries to kill the guy with evil magic!

The sheer amount of off-the-cuff musing going on here just speaks to how great of a writer Benson is, I think – his stories are always full of interesting little threads and diversions, stuff you can mull over and pick at and think about long after you’ve finished reading, the sign of great fiction. And on a mechanical level, he’s worthy of emulation too, I think – the deftness of his characterizations, the structure of his plotting, the way he sets a scene and efficiently cuts through to the heart of the matter with a short, sharp line, all of it is just spot on. Too, his ability to construct legitimate bit of witchcraftiness without getting bogged down in detail is admirable. He’s one of my favorite writers, and I think this witchy little tale is a great bit of weird fiction, and a good way to celebrate Hallowe’en!