Well, with the Yule ended and the New Year begun, we prepare to say farewell to the annual Sword & Sorcery celebration on the ol’ blog. But, as in year’s past, we have one final S&S-focused post for this, the most Swordish & Sorcerous (at least by name) of Holidays…that’s right, it’s Three Kings’ Day! And, as is my prerogative, I’m leaping out of the pulps and into the fancy digests of the 60s in order to talk about an interesting moment in Sword & Sorcery’s history! The story in question: “Not Long Before the End” by famous prick Larry Niven, from the April issue of the 1969 volume of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction!

Why have we flexed our mighty thews to leap wildly into the late 60s, you ask? Well, previous recent entries in this ol’ blog have focused on S&S in the immediate aftermath of Howard’s death, an important and delicate phase in the growth of the genre. Characters like Henry Kuttner’s Elak of Atlantis and Clifford Ball’s Rald the Thief were major steps in defining the rough outlines of the then nameless genre that Howard had created; similarly, we’ve looked at Fritz Leiber’s work, and he’s the writer who actually coined the term “Sword & Sorcery,” fer Crom’s sake! All of these are important points in the early history of the genre, moments where readers and writers were negotiating about what was and wasn’t a swashbuckling weird adventure story with swords and monsters and mightily muscled heroes.

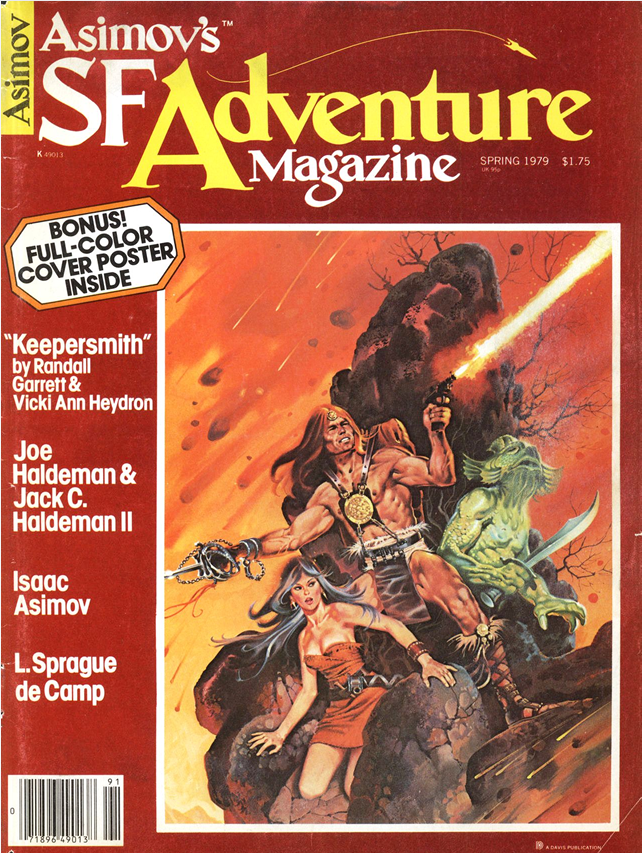

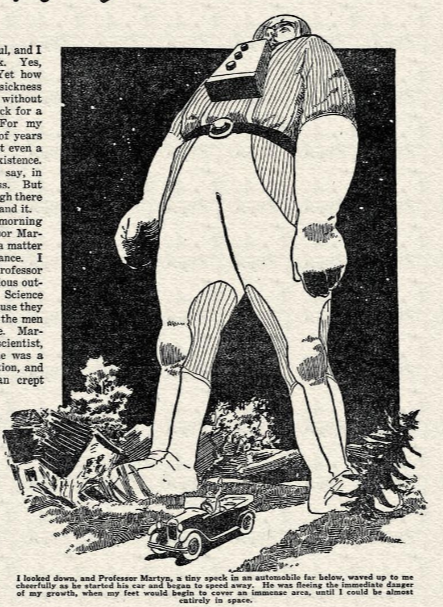

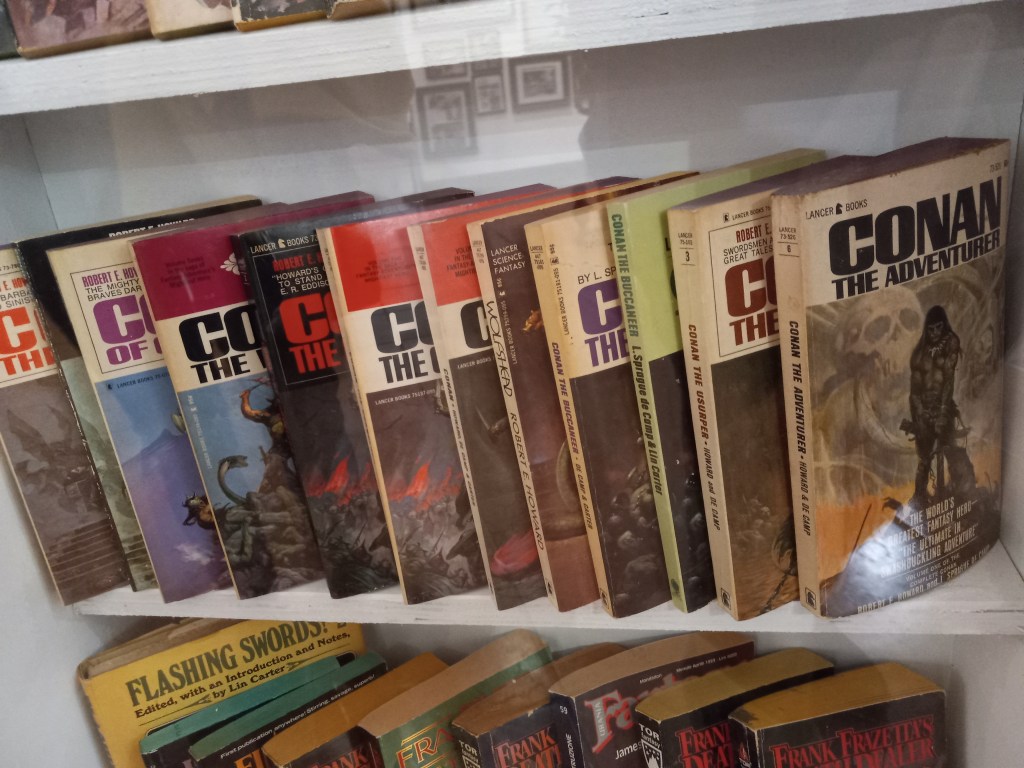

And while Fantasy (broadly constructed) was kept alive in the pages of Unknown Worlds, in important novels by Poul Andersen and Jack Vance, in the SAGA organization, and in the infamous Gnome Press Conan paperbacks, it wasn’t until the unauthorized Lord of the Rings Ace paperbacks in ’65 that things really changed. Publishers suddenly saw dollar-signs around these weirdo fantasy works, and so they sought out more, with editors like L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter digging deeply into the pulp archives to reissue old fantasy material in handy paperback format. In particular, Lancer’s Conan series, with the famous Frazetta cover that forever defined The Barbarian Archetype, was enormously important:

What’s this got to do with our story today? Well, it’s striking (to me at least) at how quickly a backlash to Sword & Sorcery develops – we’ve got Conan exploding in popularity, and Howard’s muscular approach to the genre in particular suddenly becomes a major flavor in the genre landscape, all roughly in the later half of the 60s. And then by ’69 there’s ALREADY a story commenting on/satirizing some of the themes and styles and modes of the genre, and in one of the flagship publications of the day too! That’s remarkable, and speaks to the kind of wild expansion (and passionate fandom) that S&S (and Spec Fic in general) is capable of generating.

S&S literature would have something of a tumultuous 60s and 70s, with some exciting and interesting experimentation coming from people like Michael Moorcock, Samuel R. Delany, Joanna Russ, Charles Saunders, and M. John Harrison, all of them writing if not against “classic” S&S then at least in conversation with it. That’s why today’s story, by Niven, is so important and interesting – it is a major part of a new sword & sorcery, breaking free (finally) or Howard pastiche and associated pulp reprints.

But, before we can get to the story, it’s important to address the fact that Larry Niven, in addition to being a hugely important science fiction author, is also a gigantic piece of shit and fascist scumbag. While people may fondly remember his “Known Space” setting (which he smuggled into Star Trek canon via the Animated Series), he was also an unrepentant reactionary and evil racist. With his buddy, arch-fascist Jerry Pournelle (a major figure in Sword & Sorcery fandom, btw) he cowrote a number of extremely vile novels, full of racism and dumbass rah-rah militarism; their collabs include what might be the single worst thing I’ve ever read, Lucifer’s Hammer, which is as truly deranged a race war fantasy as The Camp of the Saints or The Turner Diaries. But his bullshit goes beyond his own writing – he (with Pournelle and other assholes like David Brin) were members of a group called SIGMA, an association of sci fi dorks who offered pro bono consulting to the gov’t. Here’s one of Niven’s brilliant brain-waves, from 2008:

So yeah, Larry Niven is an enormous piece of shit, and his smugly moronic right-wing cryptofascist world view is a part of his fiction; in addition to his highly developed sycophancy towards power and authority, he’s also (like so many classical conservatives) blithely techno-positivist, which is something you’ll see in the story today! (yay!)

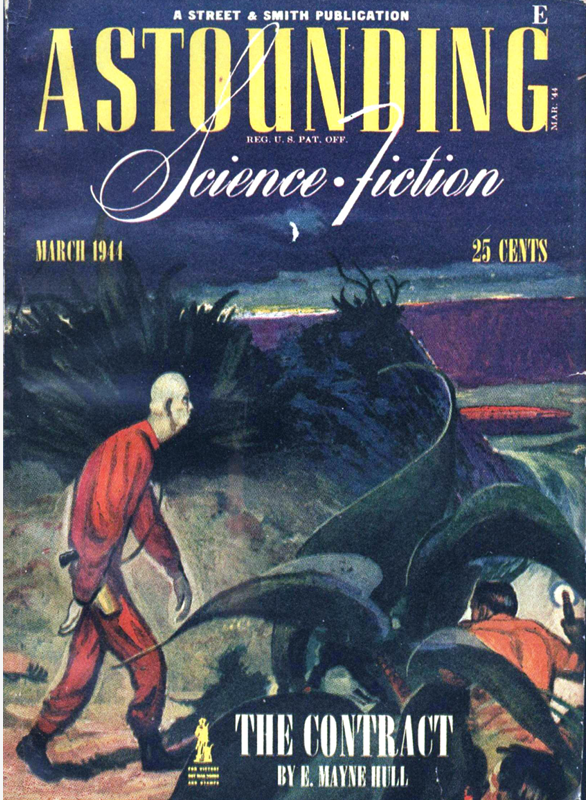

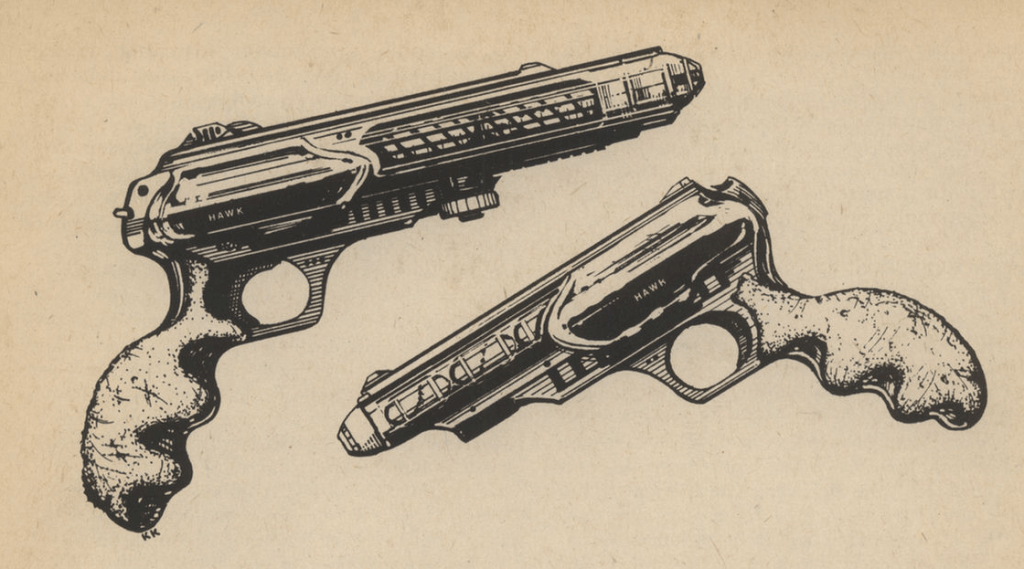

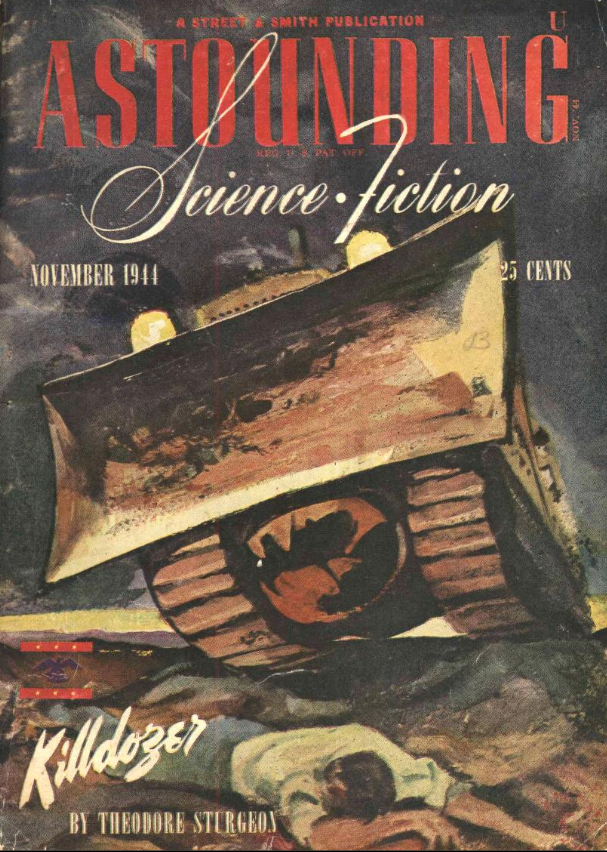

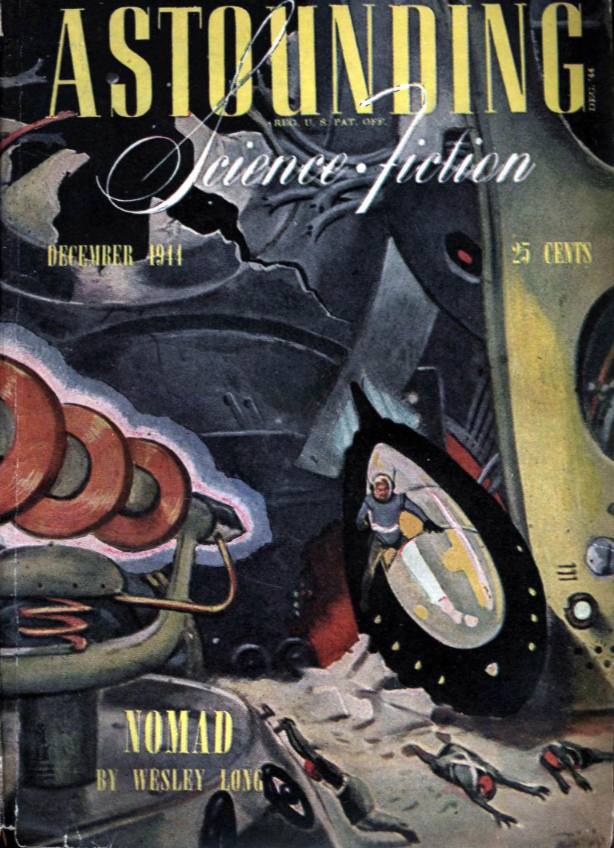

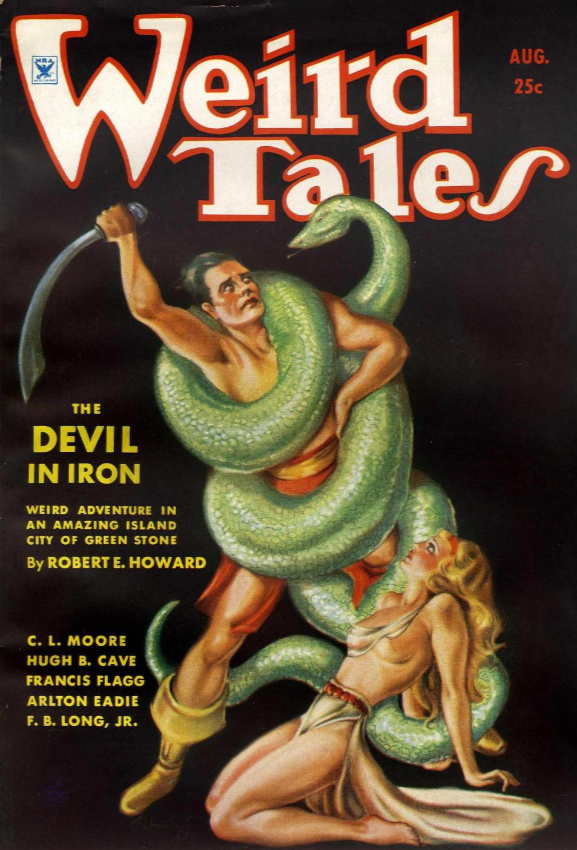

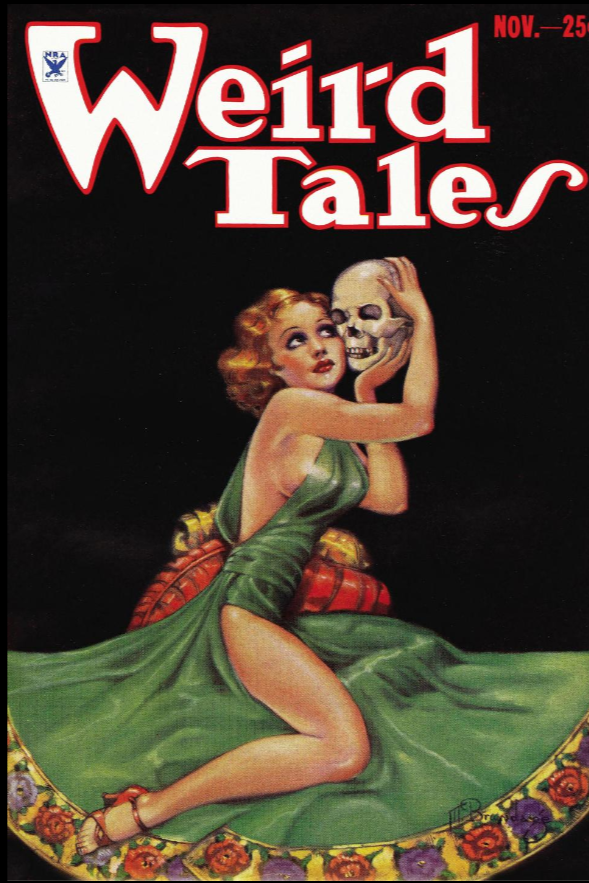

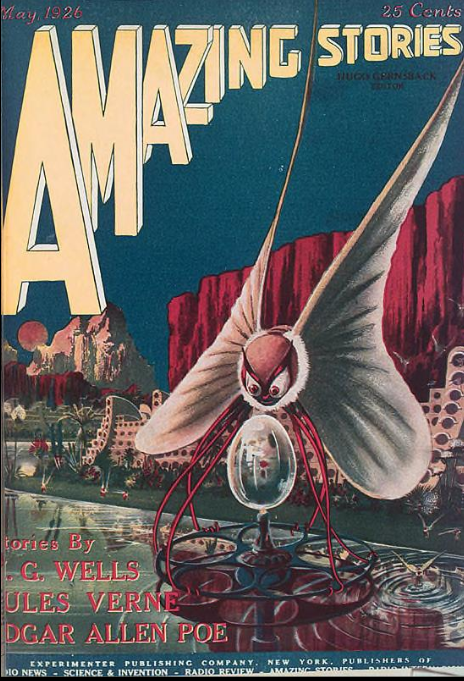

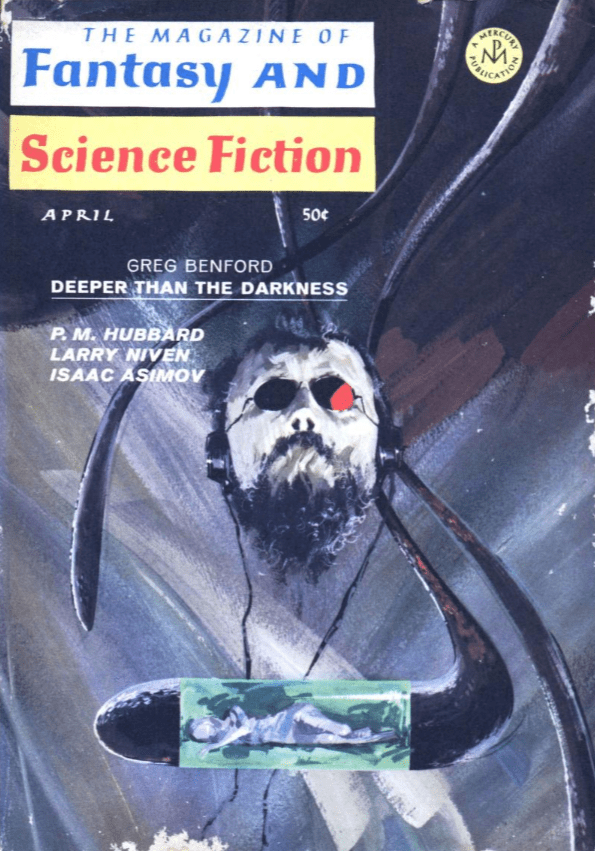

But, before we get to it, let’s look at the cover and ToC:

Now THAT is a damn cover, isn’t it? It’s by Bert Tanner, who did a number of great covers (and interiors) for the magazine, and who only died last year, if I recall correctly. The story this cover is for, Greg Benford’s “Deeper than the Darkness” is an interesting one, though there’s some uncomfortable (and very 60s) race relations stuff in it. It really goes for the whole “I am going to blow your mind: what if white people were on the bottom of the racial hierarchy!?” thing, and it can be a bit eye-rolly, honestly. I will say, though, that despite its somewhat clumsy framing, it DOES deserve some plaudits for at least engaging with the the unrest around the American Civil Rights struggle. The story has some interesting bits (and the alien menace in it *is* quite good), and it’s also a downer, too, which is always fun – this phase of sci-fi, knocking on the New Wave and therefore willing to take more chances, is exciting. It’s the kind of thing F&SF was famous for publishing, back in the Good Ol’ Days – provocative, literary stuff, often quite daring for its time, meant to demonstrate that spec fic was something to take seriously.

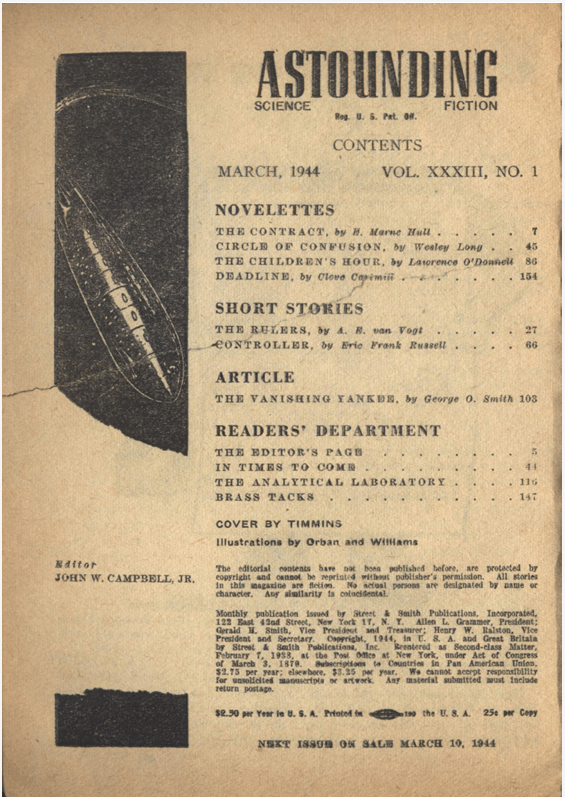

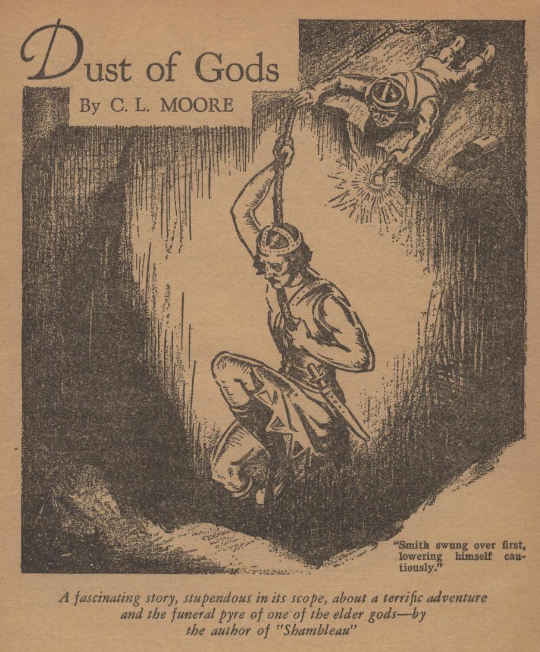

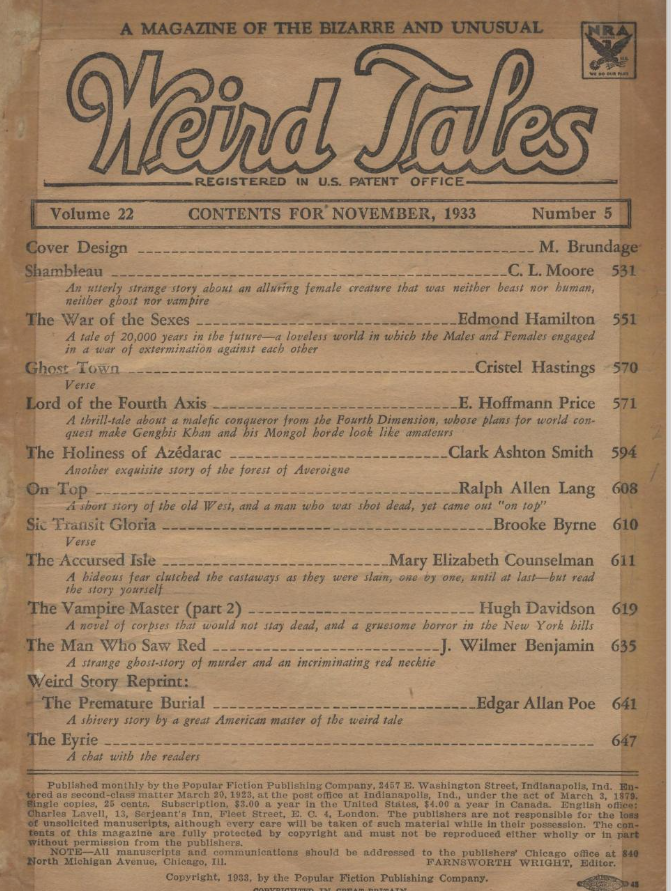

The ToC is interesting:

The only really BIG names that most people recognize today are Niven, Russ, and Asimov, and only one of them is in here for fiction. I think that reflects the extreme importance that fandom played in Sci Fi – there’s a lot of ink given over to criticism and articles and discussions of the field, right alongside the stories themselves, and its one of the key strengths that genre lit has going for it – it’s very organic and vital, forcing people reading (and writing) the stuff to be in constant conversation with each other within a curated space (something missing from today’s internet-poisoned fandom, I’d argue).

But enough! On to today’s tale!

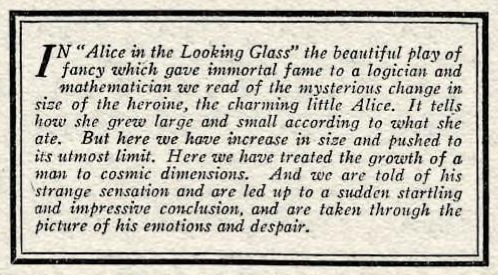

No art here, of course, but the little italicized intro makes it clear that this story is going to invert the usual order of antagonism here, something Niven underlines right off the bat in the very first paragraph:

1969, but we’re already playing around with the well-established sword versus sorcery aspect of the genre! It’s kind of remarkable, really, that the genre, which didn’t really have a name until 1961 (coined by Fritz Leiber in the pages of the fan magazines Ancalagon and Amra), was already stimulating comment and experimentation (much to the chagrin of people of Lin Carter, actually). Of course, the inimical nature of magic and the uncanny is a HUGE part of the genre, an inheritance from its progenitor genre, Weird Fiction. It’s also why the Barbarian in particular came to be such a strong and semiotically potent figure – the barbarian’s Natural strength, inherent in their powerful Body, versus the otherworldly and inhuman power of Magic. The triumph of Conan over foes like undead wizard Xaltotun is about restoring the dominance of the physical and the natural over the insubstantial and the perverse, and that becomes one of the defining themes of the whole genre.

But for people like Niven, that kind of message was antithetical to what they saw as the REAL narrative of human progress – the Barbarian, representative of brute physicality, triumphing over the specialist/technologist/intellectual was intolerable, the sort of dirt-kicked-in-the-nerd’s face bullshit that had hindered the cultural and technological advancement of the species. Niven is very explicit about this, even making a eugenicist and social Darwinist argument – swordsmen being removed from the gene pool was a net win for the species, and wizards who couldn’t kill a swordsman likewise benefited the population by being removed from it.

The kind of elemental nature of this struggle is further made clear for us by Niven’s choice of name for his sorcerer:

Swordsman vs. Sorcerer. Very clear, very straightforward.

Our sorcerer is introduced as a conscientious and competent wizard, a kind of idealized technocrat, powerful but largely benevolent. In addition, we learn that Warlock moves around a lot, because he’s discovered something:

And this diminution of potency isn’t relegated to individual sorcerers alone, mind you:

Niven, connecting the loss of magical power to civilizational collapse, is laying the groundwork for what this story is going to be about. Indeed, you might have already guessed his punchline, but we’ll get there in good time!

Anyway, like it says up there, Warlock is a particularly curious sort, even for a wizard, so he sticks around and seeks, through the scientific method, some answer as to what this phenomenon of magical loss is, exactly.

Credit where credit is due, Niven is setting this story up very nicely here. Our Warlock has discovered something absolutely fundamental to magic and, therefore, civilization, a fact that is terrible and final and immutable. Warlock doesn’t share this information with anyone, apparently our of compassion – there’s nothing to be done, so why bother anyone with it? We also learn that, a half-century or so later, Warlock has someone reconsidered his position – he’s manufactured another of his experimental magical spinning discs, keeping it in readiness, just in case.

And then we’re introduced to the second-most important character in the story. Not the swordsman, who is of course a meathead beneath contempt, but his sword:

The name of the barbarian swordsman here, in addition to the satirical grandiosity of having such a long soubriquet, is also obviously chockfull of injokes and puns (Niven loved that kind of stuff, and cowrote a novel The Flying Sourcerer that is basically devoted to that sort of thing, characters whose names are injokes among the sci-fi community). The most important part of the name, though, is last apparently patronym – Cononson, Son of Conan; this brutish barbarian is, for Niven, a stand-in for all of the swaggering and powerfully violent descendants of Howard’s work.

We’re also given an oblique and suggestive view of ol’ Hap the Barbarian’s character and history – he killed a sleeping woman to get this sword, which is itself a dangerous and potent magical artifact.

Anyway, with Warlock and Hap and Glirendree all introduced, we get into the story proper. Warlock is hangin’ out in his cave/laboratory with his wife/apprentice (yikes!) Sharla when a magical alarm goes off, indicating that someone is on the way. Warlock scrys on the interlopers…and the news ain’t good!

Sharla, like many of Niven’s characters who are women, doesn’t get to do much or have much agency. She’s vaguely important to the plot, but only as an object, not a person. Oh well! What’s ALSO interesting is Niven’s use of “mana” here, setting in motion a very important stream of magical terminology/theory that will run through a lot of fantasy lit AND role playing games. We’ll talk a bit more about that a little later, but this is an important story for that reason, too.

Anyway, Glirendree is a dangerous and powerful magical artefact, as we’ve already mentioned, and as a sorcerer Warlock has some responsibility to deal with it. He and Sharla leave the cave, with her running to safety and him grabbing some gear before heading off to confront the sword and its swordsman.

There’s some fun magic-as-a-technical-discipline bits in this part, an interesting and very sci-fi take on the concept of sorcery. It’s interesting to note how, in Howard’s stories, a fair bit of “sorcery” was just hypnotism and trickery and alchemy (but not all of it, of course – there’s plenty of hellish, outre spell casters in his work who draw on dark and unnatural power). But for Howard, this stuff was all wrapped up in mummery and obfuscation; the magic that Conan faced was always secret knowledge pursed by half-mad sorcerer-priests. Niven here is following a different trend in fantastic literature, one that has very strict, very technical rules-based magic, a kind of hyper-rationalized supernaturalism, which is an important distinction – there’s no NATURAL explanation for Warlock’s powers, but there are Logical rules to its operation. In other words, it’s not hidden or forbidden knowledge; rather, it’s a technical discipline, akin to science of engineering. This is something that Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp pioneered in their Harold Shea stories, and it’s obvious why Niven, doyen of “hard” sci-fi at the time, would take it up in his fantasy story. Again, it turns the wizards into ultrarationalists, even if their rationalism hinges around supernaturalism. It’s important to Niven and the story that this be the case, because he’s already established that Magic = Civilization.

Importantly, in his magical observations of Hap, Warlock lets us know that the Sword protects its wielder and makes them invulnerable to everything but the sword itself. A key plot point! Warlock, unable to enchant Hap or even prognosticate the outcome of a battle, gets out two important pieces of equipment – a metal disc and a rune-covered dagger.

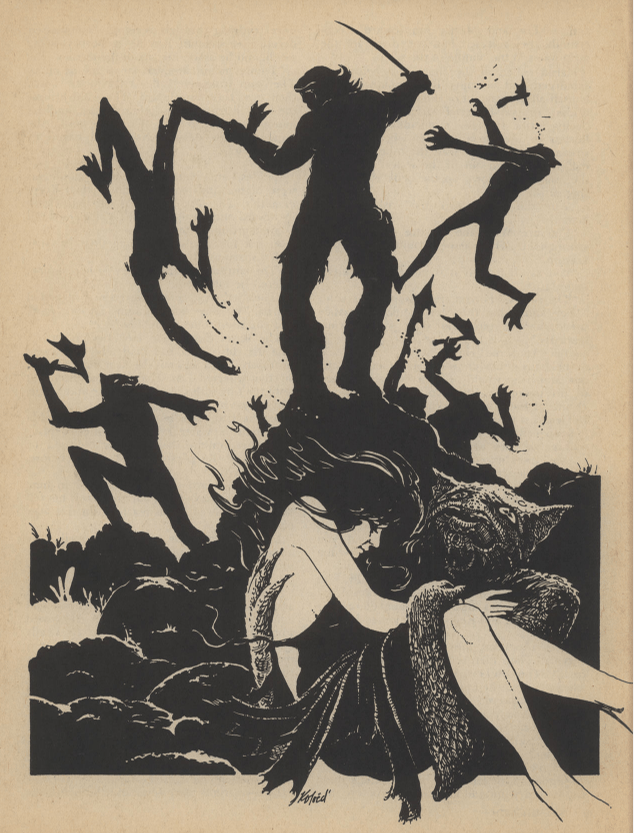

And then, finally, the swordsman and the sorcerer face each other.

An important highlighting of Hap’s scarred and formidable body here, highlighting his barbarism and the supremacy of physicality that he represents. What’s odd, though, is that just a few paragraphs later, we learn that Warlock is ALSO a slab of beefcake, through his magic. It’s an interesting inversion of the more usual sword & sorcery & bodies – Hap’s body, earned through labor and effort and with ample evidence of it having been used, is a sign of atavism and barbarity, whereas Warlock’s magically maintained pleasingly aesthetic form is a symbol of refinement and technical sophistication.

Anyway, we learn that Hap is here to free Sharla…who is there willingly, married to Warlock and learning magic. Hap apparently believes Sharla to be the victim of a love spell or something, and he’s here to free her by killing Warlock.

Warlock cuts him off with another attempted spell, which does nothing, of course. Similar failures occur when he tries to smash Hap with a magical meteor, or when he unleashes a demon from his magical back tattoo (which is very cool). And then Warlock tries one last time to reason with Hap.

There’s gotta be a bit of Moorcock’s Stormbringer in Glirendree, though there’s probably more of Andersen’s Tyrfing (which comes from the sagas) in there. Still, a solid fantasy macguffin, a sword that’s actually an evil demon. We go on to learn a bit more about the sword:

Another fun bit of Nivenesque name jokery there with “Jeery.” There’s possibly an interesting commentary of the sexual charms of barbarians there too, although it’s kind of lost under the vaguely misogynistic banter about the Rainbow Witch… really feels like the story is saying the Dumb Broad got stupid horny and that’s why the sword escaped. I dunno, I can’t help but look for the worst in Niven, because he was worst, basically.

Anyway, as Hap leaps in for the kill, Warlock tosses up the metal disc and says the word “four.” This, of course is the disc that had been integral to his epiphany in the introduction, the experiment that he kept in readiness after learning that dark truth about magic.

The disc spins and spins, glowing and getting hotter, while Warlock goes over in greater detail what we already know – magic gets used up in places, and there’re places where magic doesn’t work because all the mana is gone.

There’s some fun writing here; the part about the fallen cities and the dragon bones is good, solid stuff in my opinion. This is also a good spot to pause and discuss mana!

If you’ve ever played a JRPG or anything like that, you’ve encountered the concept of mana – a nice numerical value that defines the amount of magic a character can use. If you’ve ever looked into its origins, you might’ve been surprised to run across discussions of Polynesian religious, spiritual, and magical practices; Mana, it turns out, is a kind of spiritual property that things or people or places had, and it could be cultivated and developed. For Victorian-era anthropologists, it was an enormously fascinating concept because it seemed to have a kind of universality to it that was suggestive of ancient, interconnected humanity. It’s a lot more complicated, of course, but this pop anthro understanding came to be the general status quo understanding of the concept: mana was a kind of magical, spiritual energy. A number of Early 20th century occultists latched onto the concept, but it really took off in U.S. Pop Culture alongside all the broader Polynesian/Island craze of the 40s/50s – think Hawaiian shirts (and statehood), atomic atoll tests, and tiki bar culture.

There were a number of semi-popular and technical books on the concepts at the same time, and both the word and idea of mana was out there; Jack Vance used it in work in the 50s, though with a sense slightly closer to the “real” meaning, as a kind of mystical essence that famous objects or places could accumulate through veneration, a kind of magical force that came about as they (or people) became SYMBOLS of something. What’s interesting here is that Niven, who said he’d come across the word in a book on Polynesian culture, has slightly tweaked its meaning in this story – mana is now a quantum of magic, and more importantly, a natural resource that can be depleted.

And that, it turns out, is the great secret that Warlock has discovered.

The disc keeps spinning, using up all the magic in the area, depleting the magical effects in the area: Warlock’s anti-aging spell fails, revealing him to be an ancient and decrepit old man, and Glirendree’s true form in unveiled:

Things look grim for ol’ Hap…but then the Demon begins to experience the mana-less nature of the area they’re in:

The exploding disc in the sign that the very last of the mana in the area has been drained; Warlock is rapidly withering, the magical spring and the cavern’s furnishing and the mansion have vanished, everything has become mundane and magicless.

Mana is a finite resource, depleted by the casting of spell. The disc, Warlock explains, operates simply as a perpetual motion machine, fueled by magic…until the magic runs out, a microcosm of what will happen to the whole world, eventually.

Regardless, Hap, even with his severed hand, is still going to kill Warlock.

A clever bit of problem solving, and you’ve got to give Niven credit; “A knife always works” is a pretty badass line.

Warlock is fading fast – he’s like two hundred years old, after all, but then Sharla appears. She lifts the frail and dying Warlock in her arms and carries him down the hill towards a source of mana.

I like the little descriptions of Warlock’s failing body here – the fluttering pulse, the lose of his senses, and the way Sharla, who intellectually knew that Warlock was ancient, is still being confronted with the existential horror of decay and decrepitude. I also like her asking what color Hap’s eyes where, though not for the reason Niven has put it in – like I said, I always assume the worse with Niven, and I’m pretty sure he meant (at least partially) for this bit to be further evidence of the fickle and oversexed nature of womankind (the same thing that struck down the Rainbow Witch). Instead, I like to read this as the ambivalence of people confronted with illusion; once you know it’s not REALLY real, there’s a little bit of the magic that’s gone forever (which is the theme of this story, of course).

And that’s The End of “Not Long Before the End,” by Larry Niven!

Niven himself apparently referred to this story as science fiction rather than fantasy, pointing specifically to his rationalist mana system, contrasting it with the purely supernatural sorcery of other stories. Whether you think that counts or not (I don’t, this story is fantasy) isn’t important, though, because the real interest in it is the way he’s commenting on and writing against the fantasy of the day. Like I said, he’s explicitly rejecting the framing of traditional sword & sorcery stories, denigrating the barbarian (and, by extension, the celebration of physicality and bodily strength) as a force of social retrogression. Conversely, the sorcerer here is a paragon of rational investigation and judicious use of power, a symbol of the intellect and discipline.

What’s fun about this is that it’s happening only a few years after the explosion of fantasy and S&S; in fact, it’s in direct response to it that Niven, a proponent of rationalist and technologically triumphalist stories, wrote it. Niven’s story is a part of the larger 60s trend interrogating the fantasy genre and what it means, right alongside Moorcock and Vance and Leiber and all the rest. From the standpoint of genre studies, that period is very interesting – unsatisfied with what was, workers in the disciple are trying out new things, cutting trail into the wilderness on the edges of the stable and well-trod center.

Beyond that, it’s interesting to place Niven’s declensionist narrative, one based on resource scarcity, in the larger context of the period’s social history. The Erlichs’s book The Population Bomb had just come out in 1968, and was a humongous best-seller that had dramatically changed the way people talked about society, resources, and human population (it’s also important because the framing is one of a surging third world outbreeding the first world, a classically racist fear finding new expression in world systems theory and macroeconomic jargon). The idea of finite resources and hard limits to growth and progress were starting to occupy people’s minds in this era, and it’s interesting to see Niven take that and apply it to fantasy. He actually ends up going farther with the idea in the 70s, by the way – the Oil Embargo inspires him to explore the idea of mana depletion in more stories and, eventually, a fix-up novel based on this setting.

The 60s and 70s have been described as a period of backlash against “classic” S&S, and that’s true enough – the pages of the fan magazines are full of conservatives like Carter and Jakes defending red-blooded conan-esque tales of mighty adventurers. But the “backlash” is actually a sign of the vibrancy of the genre – people were exploring new territory through the genre, right alongside the New Wave in science fiction; in fact, I think there’s definitely a “New Wave” style of S&S being written, in some cases by the same authors (Delany’s work in the late 70s in particular represents this). And while Niven certainly had more in common politically with Carter and the conservatives in sword & sorcery, there is value in digging into this story and reading it not merely as a takedown of the genre, but as a commentary expanding on the strengths of the genre to produce more than a simple Conan pastiche.