January 19th, which was last Monday, was Edgar Allan Poe’s birthday, one of the high holy days for weird fiction! Poe, of course, is hugely important, not merely as an antecedent to what would coalesce into the genre of “Weird Fiction,” but also beyond it in the larger world of literature; for starters, just look at the huge impact his work had in other languages once it was translated – Baudelaire’s translations of (and essays on) Poe in the 1850s and 1860s were epochal in French (and Continental) literature, while Konstantin Balmont’s translation of Poe in 1895 ushered in the Russian Symbolist movement. Similarly, Arno Schmidt’s love of Poe, whom he (with Hans Wollschläger) translated and celebrated in his insanely fun (and insanely huge) novel Bottom’s Dream (which is, among other things, a novel about Poe), was an important part of mid-century German lit. There’s Edogawa Ranpo in Japan, Borges and Cortazar in 20th century Spanish lit (preceded by Landa and Alarcon who similarly revolutionized 19th century Spanish literature with Poe as a major factor), I mean, the list goes on and on! Poe was a big deal!

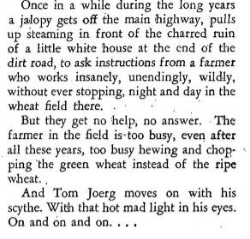

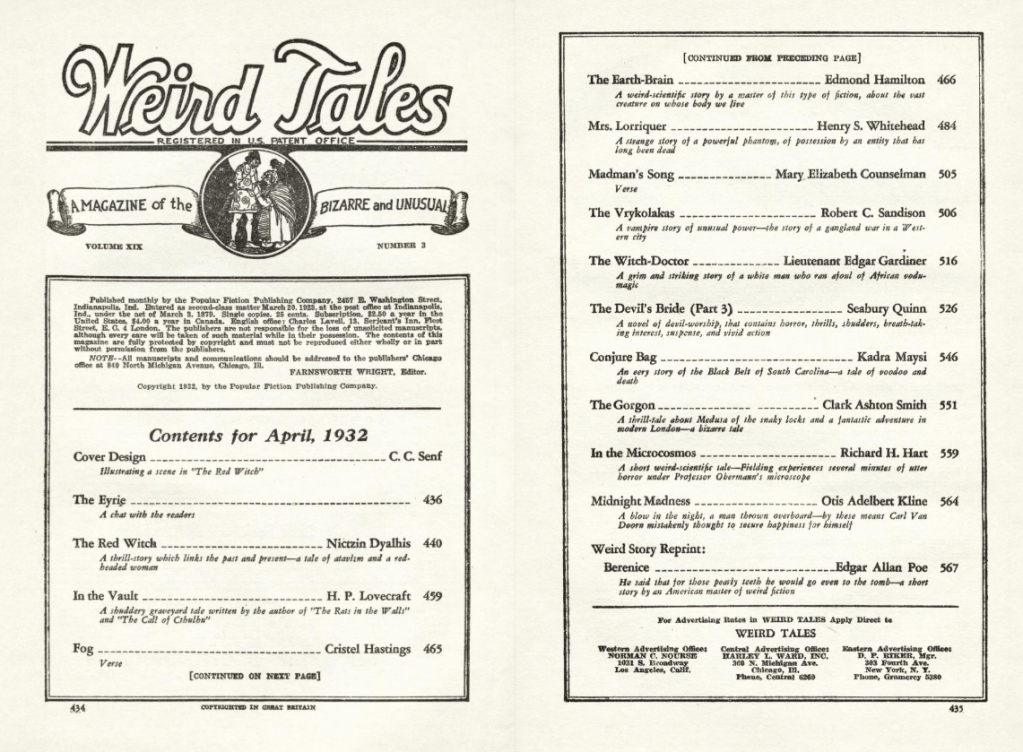

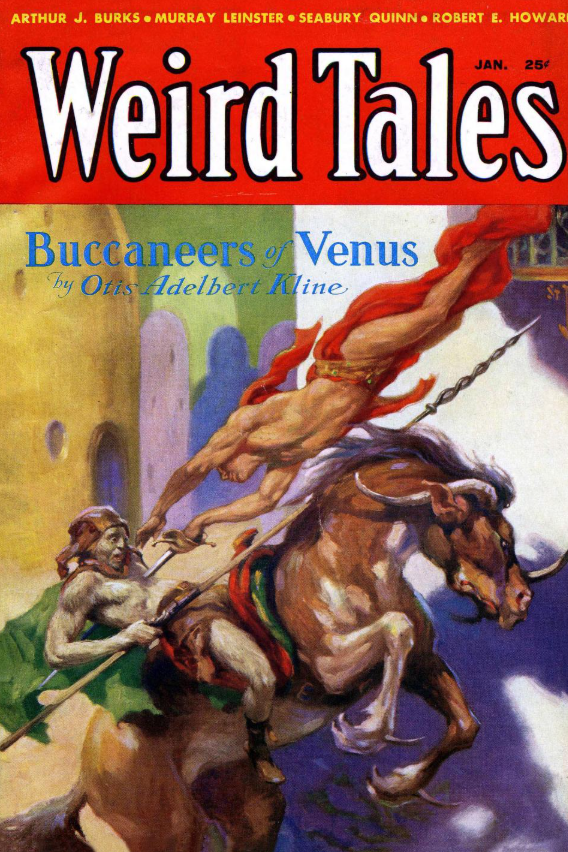

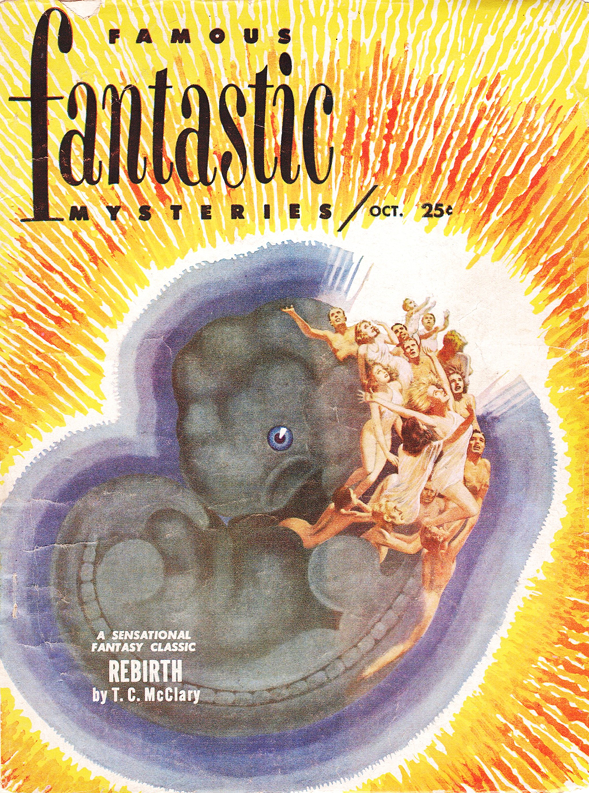

There’s even a fun bit of Poe-in-translation history in the story of Weird Tales – as a college student at the University of Nevada, Farnsworth Wright translated Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” into Esperanto and published it in the Esperantist magazine La Simbolo in the ‘teens! Wright, who would go on to become the single most powerful editor in the history of the genre of Weird Fiction, would often cite Poe as a foundational figure for the genre. And, of course, there’s Lovecraft, for whom Poe was a god; point is, Poe is hugely important to literature, both highfalutin’ AND pulpy, so how about we spend some time reading and enjoying and thinking about a very fun story by Robert Bloch about ol’ Ed A. Poe? It’s “The Man Who Collected Poe” from Famous Fantastic Mysteries 1951!

We’ve talked out little Bobby Bloch before, specifically while looking at “Notebook Found in a Deserted House,” his great Lovecraftian story and one of the few non-HPL mythos stories that rises above homage and pastiche to be something interesting, spooky, and good in itself. Interestingly, that story is also from 1951; in both of those it sort of feels like Bloch is looking back on the great influences of his writing career one last time, waving goodbye to them fondly as he begins to really develop his own voice and style.

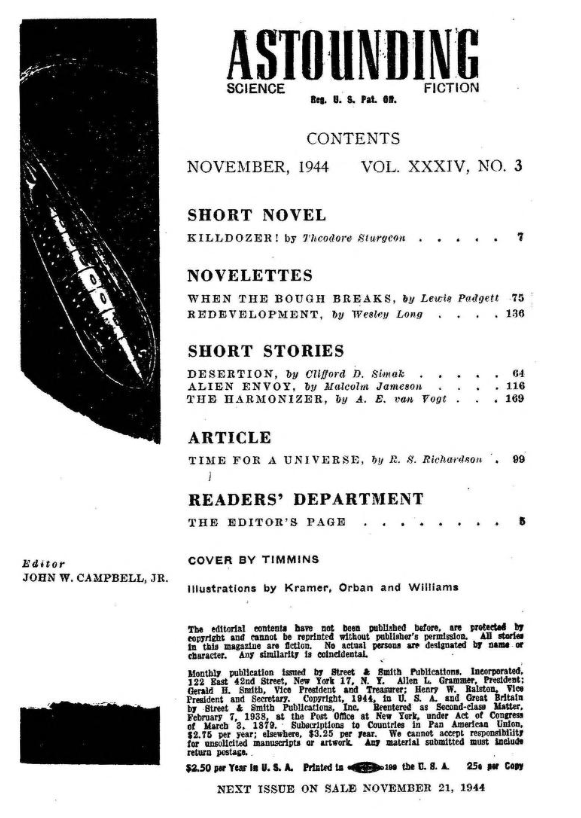

What we haven’t talked about, though, is the magazine that this story was published in: Famous Fantastic Mysteries was one of the great sci-fi-ish mags that came around as the genre really got going, a major competitor to Weird Tales. It was first published in ’39, when it was owned by the Munsey company, who had a great backlog of weird- and science fictional stories from it’s older mags, like Argosy, that it decided to exploit. For the first few years of its existence, into the 40s, FFM was mostly a reprint magazine, focusing on classics, but it later got bought by another company (I wanna say Popular, but I’m not 100% sure of that right now, and checking would run counter to the spirit of these off-the-cuff essays!) which promptly changed the policy and began publishing new fiction. Some good writers showed up in its pages, Moore, Kuttner, Arthur C. Clarke, some big names. The editor for its entire run was Mary Gnaedinger, who was a HUGE name in sci-fi back then, famous for her deep knowledge of the field.

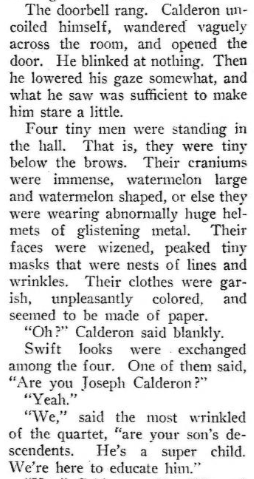

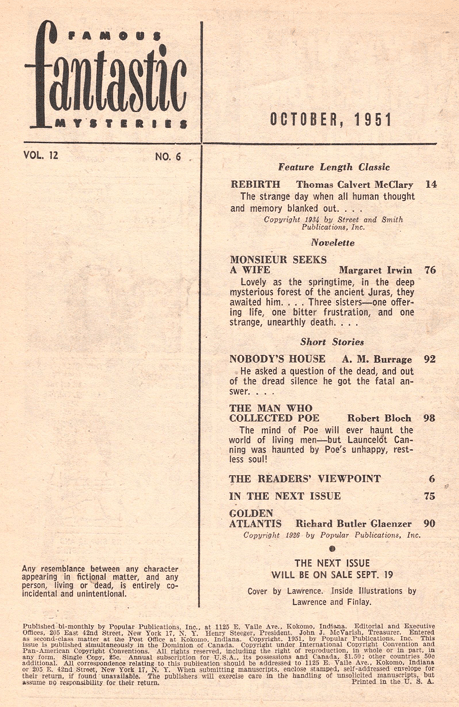

Oh, hey, it was “Popular” who bought ’em from Muncey then; you can see that on the ToC, above. Margaret Irwin is an interesting character – she was an English writer most famous for her historical novels, mostly set in Elizabethan times, but she (like so many writers from the UK) also wrote “ghost” stories (a term the brits use to cover both traditional spooky tales as well as what we’d call weird fic, too). You can see, though, that FFM focused on longer work with their reprints – that big ol’ “Rebirth,” originally from ’34, is a hefty un! But, luckily, they filled the nooks and crannies with shorter work, and that’s what we’re looking at today!

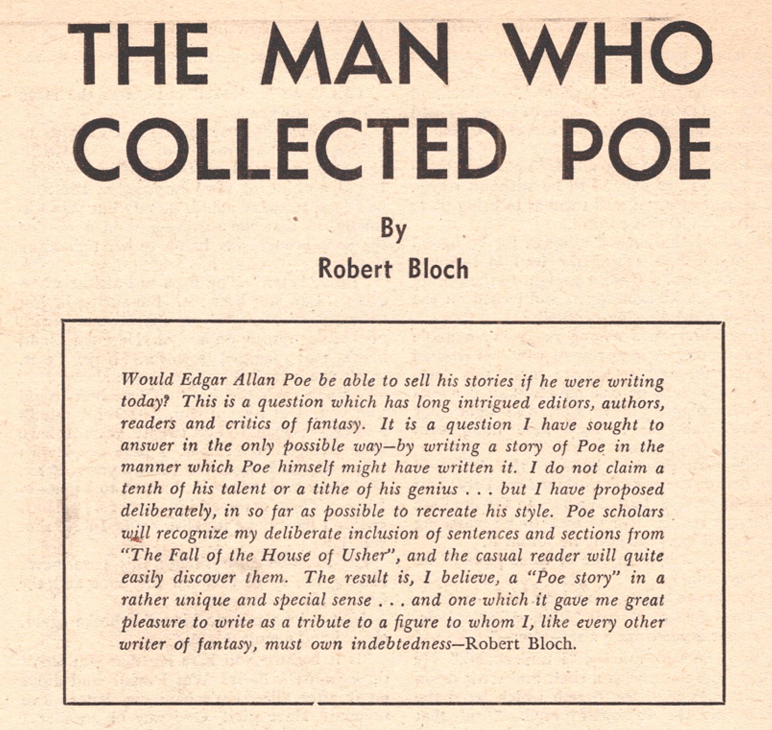

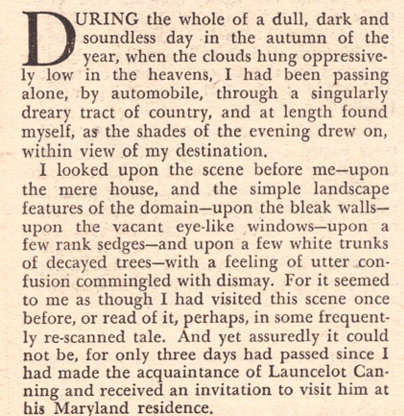

I love these little writer’s statements up front of the stories in FFM, fun little glimpses into the processes and how the author views their work. It’s a little odd because, as we’ll see, I don’t think this story really does address the question Bloch raises there (goofy and ahistorical as it is) – it’s not about whether Poe would’ve sold his work today at all, so it’s a little strange to see that point raised here. But what IS fun is that Bloch tells you, up front, that he’s grabbed a LOT of text straight from Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” and, by God, he’s right! Here’s the first two paragraphs of this story:

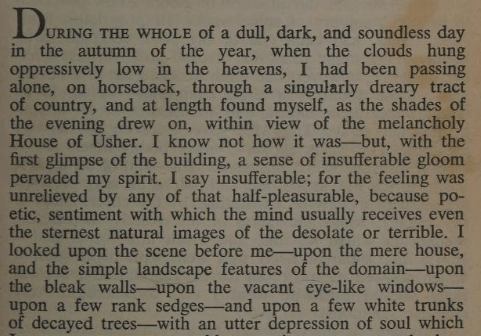

And for comparison, here’s the opening of Poe’s story:

I mean, that’s super fun, isn’t it? What I really like is the way Bloch hangs a lampshade on the whole thing in the story by suggesting that our nameless narrator seems to recognize the whole scene – which of course he would, since he’s a Poe expert who happens to be entering into a Poe(esque) story about all things Poe! It’s fun and playful, which is one of the hallmarks of Bloch’s writing (and why he’s such a good horror writer).

Anyway, we do get a name here, and it’s another deep cut from Poe’s story: Launcelot Canning, who is the fictional author of the fake book (The Mad Trist) that Roderick Usher reads aloud while his sister, Madeleine, is clawing her way to freedom in the tomb beneath the house. As an aside, that part of “Usher” is a lot of fun and is an interesting earlier example of what would become a hallmark of Lovecraft and his circle of weird writers – the inclusion of a fake book in among a some real ancient texts.

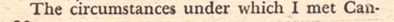

Again, Bloch was very sincere in saying he was mining “Usher” directly here – the allusions come thick n’ fast in this story! It makes for a fun read after reading “Usher” honestly, and I’d recommend you do that too! But, anyway, back to the story:

A good weird intro to the character – ol’ Lance Canning here is the world’s greatest collector of Poe-mobilia, something that, while interesting enough to the narrator, isn’t the real hook that reels him into Canning’s orbit. Rather, it is Canning himself, who is just a straight-up oddball seemingly right our of a Poe tale:

I really like that little joke at the expense of people with obsessive interests – the bit about wanting to figure out EXACTLY when Poe first grew a mustache is a funny line!

Anyway, our narrator accepts Canning’s invite out to the ol’ home place in Maryland (the state where Poe died and is buried, an important point to this story). The house is, of course, the Usher mansion, though without moat and tarn, and the rooms are straight outta the story too. Canning is languidly reclining on a couch, and our narrator feels like there’s something forced, or maybe manic, about his greeting, but our guy here just chalks it up to his weirdness. Moreover, he comes to realize that Canning is, literally, a BORN collector:

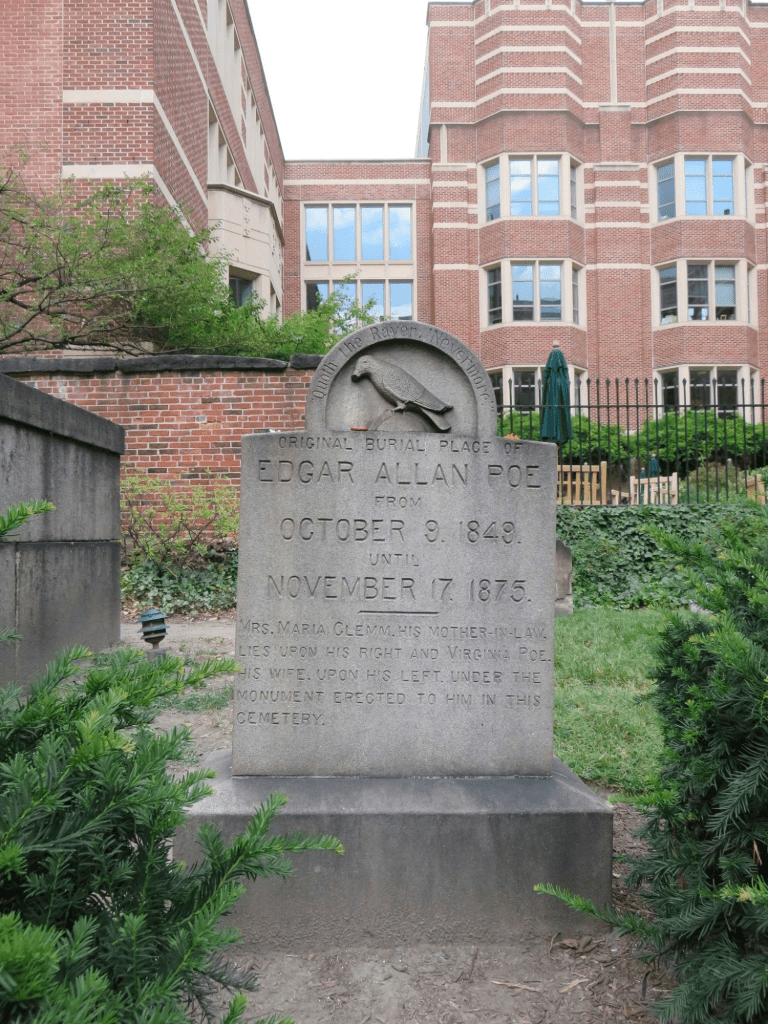

As a brief interlude, here are the graves themselves in Baltimore, which I visited during a conference in Baltimore a few years ago. This first one is the original monument:

And here’s the newer one, which was indeed commissioned by notable and literary members of Baltimore’s citizenry in 1875 and which necessitated an exhumation and reburial of Poe’s remains:

In particular, it’s this grandfather, Christopher Canning, the one who helped fund the new monument, that built the bulk of the Canning collection. Lance shows off some of the insanely rare and insanely valuable pieces:

This is some fun bibliomania, and the “commingled pride and cupidity” is a great line that really conveys the very specific affect of Canning here. It’s not merely greed or snobbery – it’s a kind of all-consuming obsession, something Poe wrote about often. It’s also fun to see the long list of Poe works here, especially the weird Conchologist’s First Book, which is a real fun deep cut in Poe’s oeuvre. And this obsessiveness seems to run in the family too:

Some fun metacommentary on the kind of mania that can develop around a subject of study, as well as an important part of the story – we learn that ol’ Grandpappy Canning was not above rank thievery to get what he wanted for his Poe collection! Our narrator tries to explain Canning’s grandfather’s truly all-consuming obsession with Poe by asking if there wasn’t some deeper reason behind it? Perhaps the old man thought he’d been related to Poe in someway?

Canning then goes on to talk of his father who followed in Grandpa’s footsteps and became a reclusive scholar and collector of all things Poe, in particular focusing on letters either from, to, or about ol’ Edgard Allan Poe. While Lance gathers these particular pieces, he pours them some amontillado (natch), and the two of them proceed to get increasingly toasted as they look over the collection.

Aside from the fact that the above passages are just good writing, I like the kind of mounting (or, perhaps “deepening” is more appropriate here) intensity here – Canning began with his Grandfather’s collection, a remarkable but still very MATERIAL kind of thing, full of rare and valuable books. But now we’ve moved beyond the man’s work to the man himself. Canning’s father was obsessed with the letters, little glimpses into Poe the person, and that kind of voyeuristic and intimate examination of a person’s life is a very intoxicating thing, you know, just as much as the wine they’re drinking. It ALSO nicely sets up a kind of generational escalation to this Poe obsession that afflicts the family Canning, right? Grandpa was all about the material of the man, his son was getting into the psychology and life of Poe…so what does that leave for the grandson, Launcelot Canning?

A fun little nod in the text there to Arthur Quinn who wrote, in 1941, the excellent and still definitive biography of Poe (you can read the 1960 edition over on archive.org here, btw).

Lance cracks open a chest and shows our narrator the intimate objects of Poe’s life, a helluva collection. And while he’s doing so, Lance seems to be afflicted with a mounting panic or dread, like he’s juuuuuuust barely tamping down some kinda freak-out.

His reserve almost cracks when our narrator asks about a small box in the chest.

So now we’re getting to the details of the hinted-at mysterious death of ol’ Grandpappy Canning. The two of them take a trip (with more wine) into the weird Poe-themed fun-house mansion that is Canning Manor, wandering down a dark hallway and dismal stairs into the bowels of the castle-like edifice before coming to a huge, copper-lined door:

I mean, that’s excellent stuff right there. Love the wildly Poe-flavored rantings of the madman, for one thing – it’s fun to see ’em purely as allusions, but within the text it’s interesting because we, as the readers, can’t be sure WHAT exactly is happening here – did ol’ Christopher’s Poe-obsessed brain break, and THAT’S why his rantings are all Poe-flavored…or is something else happening, something darker and much weirder? We don’t get an answer immediately, but we do get a nice reveal of Christopher Canning’s ghoulishness:

Just wonderful! It’s really fun to use the Real Life exhumation and movement of Poe’s body as the seed for a story of body theft, isn’t it? It also suggests the joke (or a joke, as we’ll see…) behind the title of this piece. Christopher Canning did, indeed quite literally, Collect Poe.

And what of the little box, which he was clutching when they found him mad and raving before the door of the secret tomb of Edgar Allan Poe?

If you’re a fan of Lovecraft (as Bloch was), you might have an inkling of where this story is heading, but if not, we’ll come back to it shortly.

Lance leads the narrator back to the study, where he continues his tale – his Father kept secret the fact that Poe’s corpse lay in the tomb beneath the house, and only told Lance about it as he lay dying. Even so, it was several years before Lance even found the key that would unlock the door to the secret, shameful tomb. And yet, with that key, somehow, Launcelot Canning is confident in stating that now HE, more than his grandfather or father, is in fact the Greatest Collector of Poe! Wait, what’s that now?

The storm builds in fury, and Lance takes up Poe’s childhood flute and begins to play madly on it, in a scene reminiscent of Roderick Usher’s guitar-playin’ while the storm (and his sister) creep upon the doomed house. Seems like a weird scene, but I guess the wine must be good because, rather than gettin’ the Hell out of Dodge, our narrator decides to peruse the bookshelves of his obviously mad host (as you do when you’re in a weird tale):

Oh hell yes. That’s right – this is Bloch before he’d shed himself entirely of his Lovecraftianisms, so of course there’re forbidden books of dark lore and evil magic here…and they’ve been well-thumbed too!

“…what can be summoned forth if one but hold the key.” hmm…

Anyway, THIS is apparently enough for the narrator, who refuses his ninth glass of wine and says he must, at last, be on his way. This panics poor ol Lance, who seems to desperately want to have someone there with him, particularly on this stormy night. Our narrator demands that Canning admit that all this stuff about the stolen body and the tomb and all is a hoax, but Canning says its all real. And, in fact, he can PROVE it:

A very fun reveal – secret Poe stories that no one has ever read! But how can this be?

Super fun, isn’t it? And if it weren’t for those magical Lovecraftian tomes mentioned earlier, you might think that the Narrator has hit on the solution here, right? That Lance Canning, a la Norman Bates (who hasn’t been written about yet) has monomaniacally BECOME the dead person who is the focus of their obsession. Maybe Canning has so steeped himself in Poe that he has, in some mad way, convinced himself that he IS Poe, right?

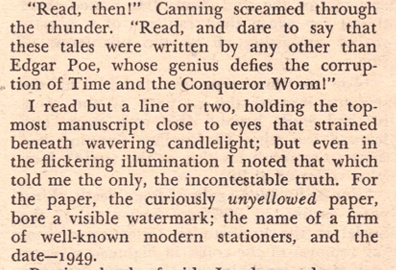

Well, surely that IS what has happened, right? New paper, one of the stories is dated 1949…clearly Canning is just nuts and thinks he Poe. MYSTERY SOLVED!

But Canning persists in his denial:

A boxful of dust, you say…what does that sound like…

That’s right – this IS a Lovecraftian mythos tale after all! Canning, like Charles Dexter Ward, has used the essential salts of the corpse to REANIMATE the dead!

It’s a pretty fun little twist, and one you might not have seen coming – after all, even knowing that Bloch began his writing life as a Lovecraft acolyte, you might assume that, by ’51, he’d transformed himself into the writer who was more interested in the twists and turns of a fucked-up mind than in weird gibbering cosmic entities from behind. And it’s fun to see him set that up here – the idea that this family, so obsessed with Poe, would eventually produce a deranged member that believed himself to actually BE Poe is a perfectly good bit of weird horror, you know what I mean? But in many ways this is not merely a story ABOUT Poe…rather, it’s a story about the influence of Poe, of the way an older writer can still impact people from beyond the grave. And, of course, Bloch is also thinking about how that influence was felt by Lovecraft, and how he was, in many ways, the grandson of Poe and the son of Lovecraft, at least from a writing perspective. It’s a neat, weird mediation on influence and writerly genealogies!

AND it’s got an undead Poe writing impossibly horrific stories from beyond the grave!

We’re rapidly approaching the end, so of course we start hearing the metallic pounding on the tomb door below echoing through the house!

A chilling image, and a great, horrific concept too: Poe’s new material is informed by concrete knowledge of what he could only have imagined in life. His old published work is merest preamble to the true horror of his undead writings! It’s all so huge and over the top that it really can’t be beat, it’s so much fun!

Of course, Poe has escaped the Tomb and has been making his way up the stairs and through the house towards the study. Our narrator pushes aside the panicking Canning (knocking over a flaming candelabra) and flings open the door!

And that’s the end of Robert Bloch’s “The Man Who Collected Poe!”

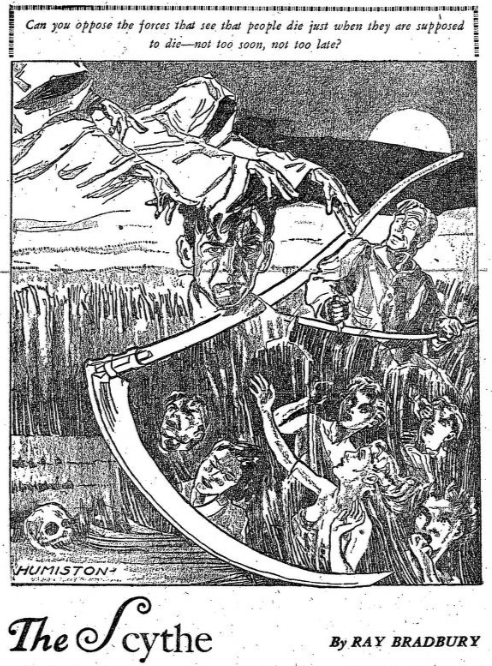

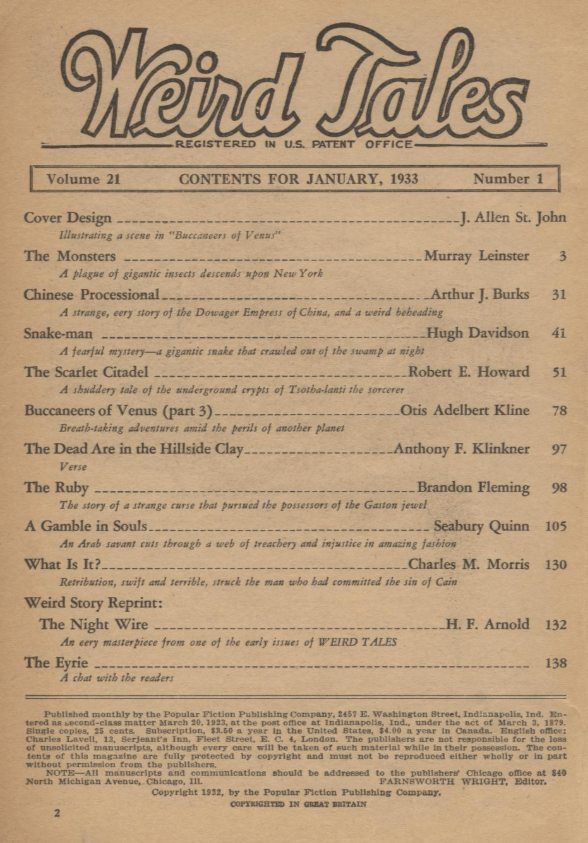

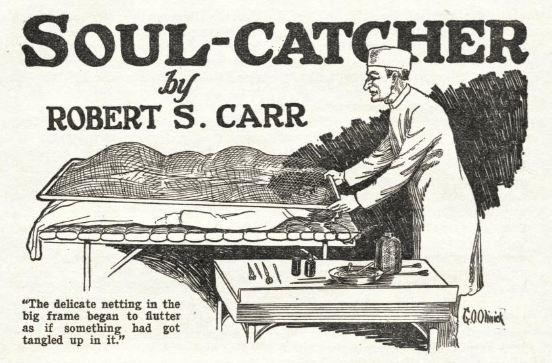

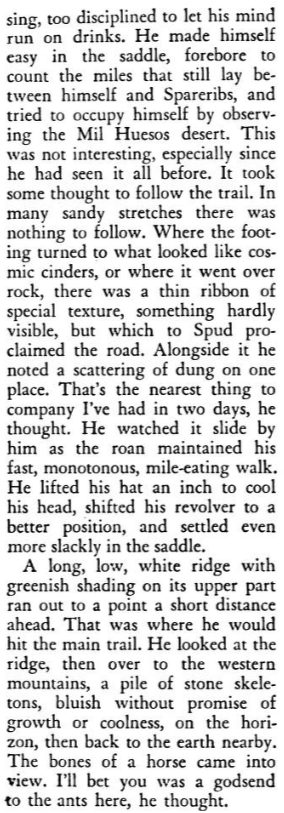

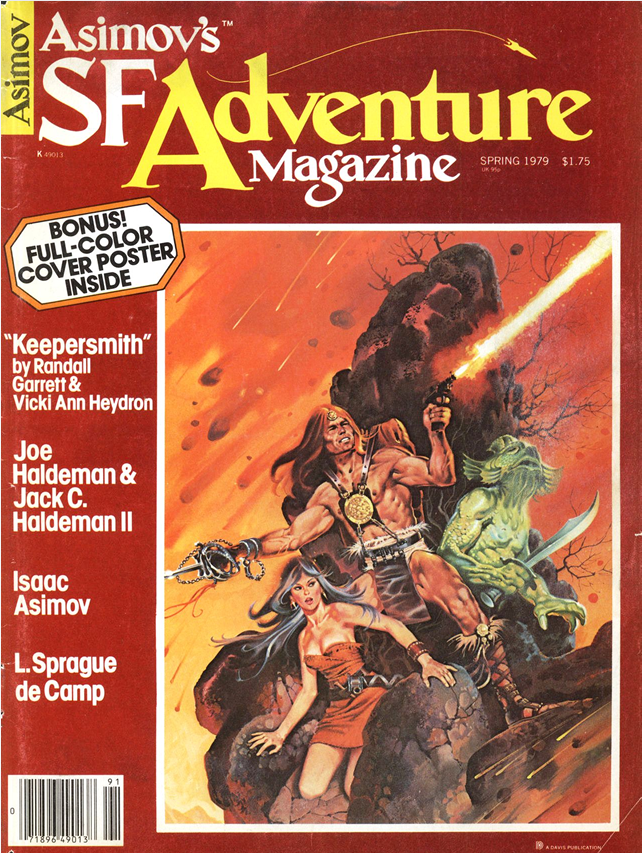

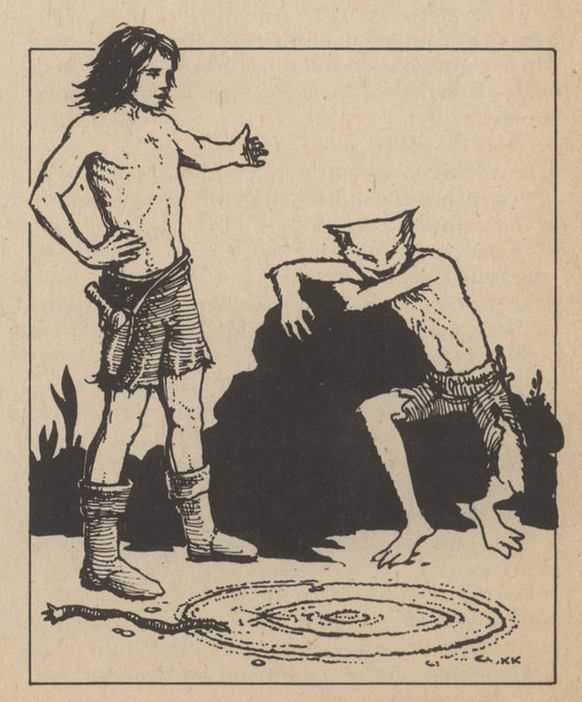

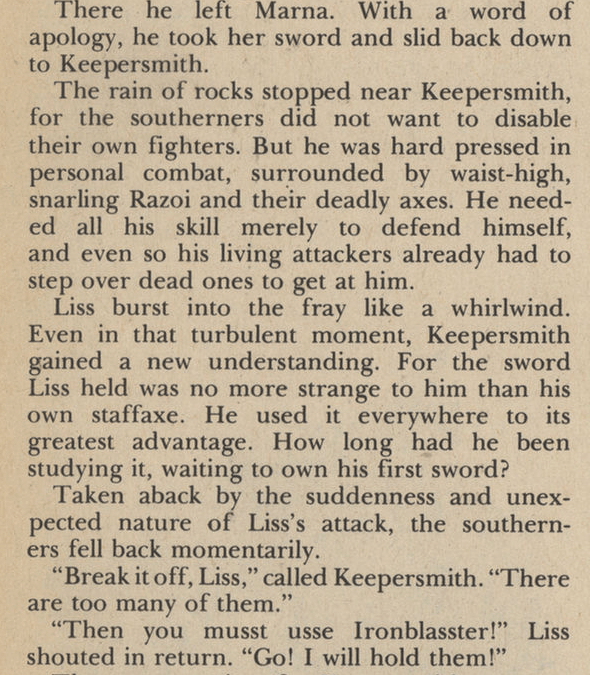

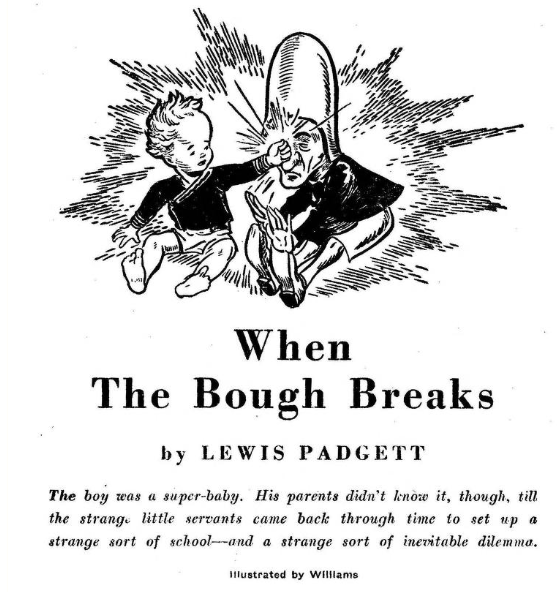

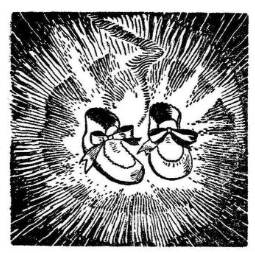

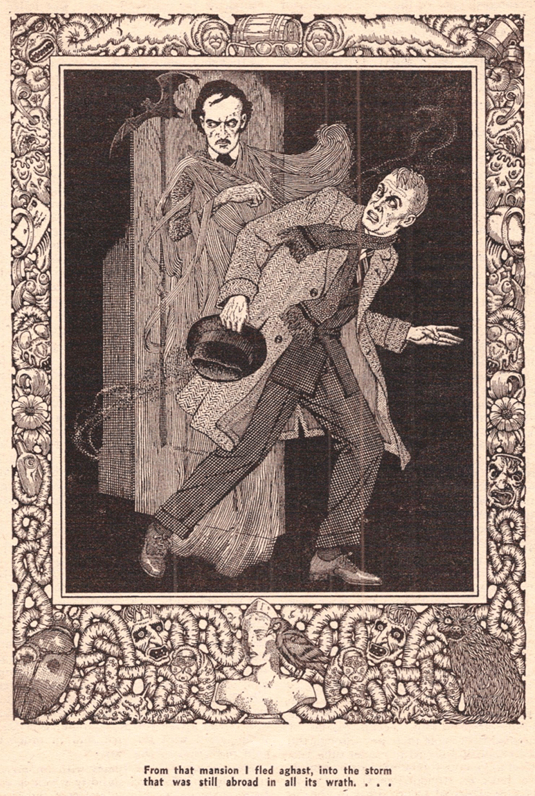

This story has some great art with it that sorta kinda gives away the plot, so I’ve saved it for last:

A wonderful piece by the great Lawrence Stevens showing the moment of the revivified Poe’s appearance. I really like the border there, full of little allusions to Poe’s works. A great piece all around!

Obviously, I love this story. It’s just a blast, and you can really see Bloch is having fun writing it, playing with the original text from “Usher,” really relishing the language and vivacity of Poe’s words. But beyond that, I think it’s a really interesting example of a writer very explicitly exploring both their genre in general and those in it who influenced them very specifically. And, not to be schmaltzy, but I think there’s a real affection and appreciation on display here, both for Poe and Lovecraft, writers who were very important to Bloch at one time but whose work he’s moved (and will continue to move) away from as he develops and grows and ages.

And, like I said above, it is interesting to see Bloch musing on his changing interests in his writing – there’s still the Lovecraftian weirdness here, of course, but there’s also a preoccupation with minds and psychology, highlighted both in his own writing as well as in the sections of “Usher” he chose to use. It’s also reflective of Bloch’s deeply Freudian impulse to look his progenitors square in the face and, if not reject them, at least put them to bed. Poe is the grandfather of all horror writers, and for Bloch Lovecraft was a sort of literary father – for Bloch to grow he has to step out of the shadows, otherwise he’d be in the shoes of Launcelot Canning, brooding over his collection, unable to live his own life and write his own work.

Poe is a writer who often suffers from peoples’ assumptions – the idea that he wrote only horrible, macabre, freaky shit is a common one, and tends to color most peoples’ views of his work. But a careful reading of Poe shows, I think, that he’s deeply interested in consolation after the horror, in looking for solace in the face of unimaginable terror and tragedy. And while he’s mostly just a Monster in this story, I think that there is a kind of catharsis here – Poe is, of course, freed at last, but so too is Canning. The conflagration that consumes him and his collection (and its centerpiece, Poe himself) is a cleansing fire, in more ways than one!