Look; the pulp ain’t gonna strain itself, you know what I mean!? So here we are, yet again, to enjoy some spooky season fun with another little horror tale that I personally dig. This time it’s Julius Long’s neat and very short story, “The Pale Man,” from 1934!

I kind of feel like the 30s, and especially the early 30s, are the real sweet spot for Weird Tales. Not to say that there’s not great stuff in the 20s and 40s, of course, but this block from, like, 30-36 or so is really when the magazine was at the height of its powers, in my opinion – it had figured out, by and large, what weird fiction was, it was probably at it’s most well-oiled in terms of editorial workflow, and of course it had developed a stable of consistently interesting and often very good writers. Chief among them are Lovecraft and Howard, of course, but there’s also a good body of second-stringers (no offense) that are getting to play around in the genre in interesting ways. Honestly, it feels like there’s a real Goldilocks Zone in genre stuff where the broad outlines of what makes a story a part of that genre are in place and tacitly understood BUT NOT YET ossified, so you get a flush of just crazy unbridled creativity that you’ll never see again. Early sci-fi is definitely like that, and I’d argue there’s a similar trend in detective fiction. It just feels like there’s an interesting artistic vitality that arises at that point, and the early-to-mid-30s are that for Weird Tales!

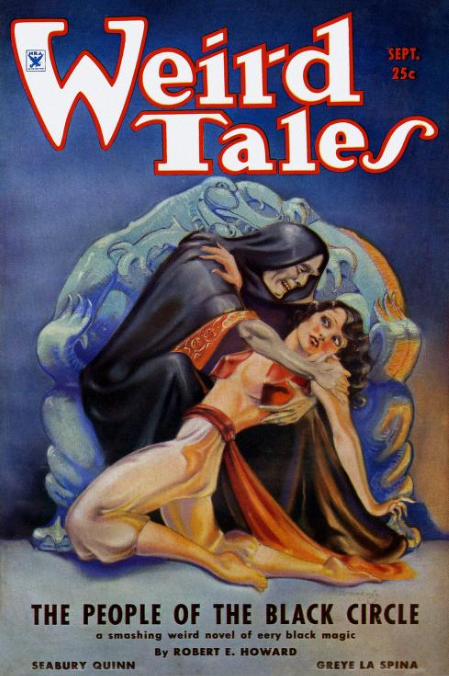

Speaking of Howard, check out that cover!

That is, of course, a Brundage classic. Love the impossible way that vest is hanging on! Really dig that snaky, dragony motif carved into the dark throne too. The story it’s illustrating is one of REH’s best, one of my personal favorite Conan adventures…in fact, so much so that I’ll probably write about it during my traditional sword & sorcery binge over christmas. So we’ll save it for now and instead, with tremulous steps and shaking hands, check into “The Pale Man” by Julius Long.

Julius Long is one of those enigmatic pulp authors with very little biographical information. He wrote a fair number of horror tales early on, but became much more active in detective and crime pulps, especially in the “two-fisted, investigatin’ lawyer” subgenre. I’ve seen some info online that suggests he himself was a lawyer, which makes sense! Today’s story, “The Pale Man,” is probably his best piece of fiction in Weird Tales, so let’s dive in:

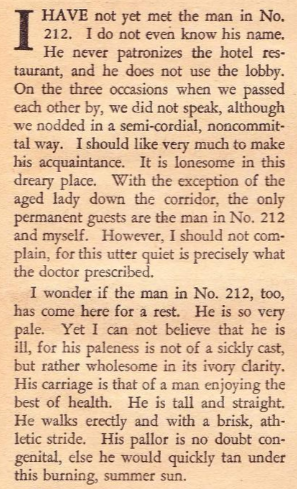

The unnamed narrator immediately conveys a strange (some might say…morbid?) fascination with an extremely pale who, along with himself and an old lady, staying in a hotel somewhere. It’s good, quick narration, and the second paragraph immediately establishes that the narrator came here for “a rest” of some sort. The discussion of the pale guy’s paleness is interesting, though – it’s not sickly, but rather wholesome, and the narrator describes what seems like a fairly attractive, vibrant fellow.

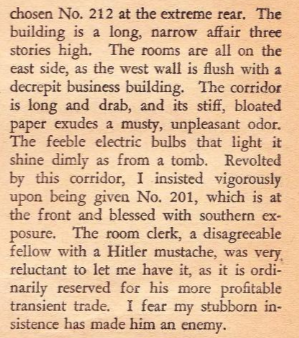

Less salubrious, however, is the hotel itself!

Smelly, dark, decrepit little hotel seems like a weird place for some recuperation, but that’s probably because the narrator isn’t exactly in the greatest of financial health either; in a later paragraph, we learn that he’s a lowly assistant professor, even after 30 years of work at the university. This indignity he attributes at least partially to a lack of assertiveness on his part. Just a bit of character development that helps to paint a picture of a worn-out, sick-and-tired character, sent off by the University president for a rest somewhere nice and quiet for a while. The OTHER thing to point out, though, is that reference to a Hitler ‘stache! Even in 1934 everybody knew that it was both a stupid looking mustache AND a signifier of assholery. There’s also a good burn on grad students later:

The loneliness the narrator writes about is kind of affecting though, isn’t’ it? It gets worse for him, too – after a week, he haven’t been able to strike up a conversation with anyone in the town at all, and STILL hasn’t been able to meet the fascinatingly pale character he’d noticed. Interestingly enough, the pale man is no longer staying in 212 – he’s moved one door down, to 211. But despite this increase in proximity, they’re still only nodding acquaintances.

There’s a real seductive, sexual quality to our narrator’s interest here, and I don’t think that’s just my reading; he really seem to be thinking about it in those very terms. The “I am not the sort to run after anybody” line is really suggestive, and we the readers know it to be disingenuous, since this pale dude is obviously a huge focus of the narrator’s thoughts and attentions. In fact, after protesting to much, in the very next section the narrator is musing about where the pale man takes his meals, since he never seems to eat in the hotel. We also learn that he’s changed rooms AGAIN, this time to 210. The narrator even plays out a kind of flirtatious exchange in their mind that uses this information:

This continues, of course – the pale man moves one more room down, the narrator is obsessing over the pale man, wondering where he goes, what he does, why he can’t settle down. You can almost imagine him laying on his bed, kicking his feet, making a vision board of the palest motherfuckers in history surrounded by hearts and doves. Then the old lady in 208 dies, and the pale man moves from 209 into her room, closer still!

This is a romance, at least in the narrator’s mind. “He favored me with a smile,” “My man of mystery, “I like to imagine that he speaks the exotic tongue of some far-away country,” all of this is very dreamy and kind of surprisingly steamy, honestly. There’s real longing here, and also sadness, in the final lines – you get the feeling that his career troubles are a handy label for maybe larger regrets in his life.

But the narrator’s health troubles impinge on him suddenly. He awakens prone on the floor, and he cannot remember how he got there. We learn that, while he’s been sanguine about the whole thing, it seems like a lot of people consider him to have been quite sick, possibly even near death! But our narrator doesn’t think so:

As a note, I think that “the loneliness of a bachelor for the loneliness of a husband” line is where we get the confirmation that the narrator is a man.

But hey, it’s not all inexplicable comas and sickness! The pale man has leap-frogged down to 203, with only one room separating them! Everything’s comin’ up Milhouse!

The narrator has another attack and is bedridden for a few days. In fact, a local doctor comes by, and seems to make it very clear that the narrator is not doing good. Must be some kind of heart trouble (indeed!) because the doc advises our man to avoid stairs, that sort of thing. The clerk seems convinced that the man is on death’s door, which of course our narrator discounts. In fact, he seems primarily annoyed that his bedrest is going to keep him from learning about or even seeing the pale man.

But, walking the hall one day, our narrator happens to pass room 202, the one next to his own, and who do you think he sees?

Our narrator follows through on his resolution and demands the clerk tell him who this pale fucker is. I’m sure you’ve guessed his answer, but here it is:

Dun Dun DUN! Further questioning reveals that there’s never been anyone else but the narrator and the late and lamented old lady in 207. No other guests at all, and certainly not a pale guy who has been moving his rooms over and over again. And with that information, our narrator achieves enlightenment:

That’s the end of Julius Long’s “The Pale Man.”

I like it; it’s a good, quick tale, and although I think it’s pretty obvious what’s going on very early in the story, that’s not necessarily a weakness in weird fiction. There’s a certain pleasure in seeing HOW the story is going to navigate towards the foregone conclusion, and I think ol’ Julius Long here handles it well. The writing is good too, on a technical level – the narrator has a real voice, and the conversational tone is nicely balanced by the obvious fascination, weariness, aggravation, and regret that the poor narrator is feeling. Also, the scenes with the pale man are sufficiently strange without being too overly gothic. I mean, I feel like we know, immediately, that this pale man is the specter of death, so him just kind of smiling and then later smoking a cigarette, as opposed to huge spooky theatrics, is great. I do feel like the title should be changed, though, don’t you think? “The Pale Man” in conjunction with that first paragraph seems to give away the game too early.

The sexual subtext in the story IS interesting, though. You don’t want to overinterpret anything, of course; I honestly think there IS often a real naivete about sex and particularly male homosexuality in a lot of media from this era, a product of the practical realities of a strongly homosocial society, I reckon. Similarly, I think there’s an almost knee-jerk “Aha! Gay stuff!” reaction to reading these older works now that is equally unnecessary and often obfuscatory – the constant eyebrow waggling about H.P. Lovecraft comes to mind here. But it seems hard NOT to have a queer reading of this story, on some level. The language is so obviously romantic, and the narrator’s obsession seems almost giddy (for example, the way he’s worried that his opening line might be too corny, and his resolve to work out a better one). Like I said, we don’t know much about Julius Long, but this language feels very lived, you know what I mean?

There’s also a subtext in the constant refrain of the narrator’s professional failings that’s interesting – not to put too fine a point on it, but there’s a real sense that he never consummated his career, you know what I mean? And it’s often juxtaposed in the text with his failure to strike up a conversation with the pale man, a recognition that his ineffectiveness and failure to be assertive about his desires has caused pain in his life. It’s a subtle and affecting theme!

Now, I think you could make the argument that the longing that the narrator is feeling, the desire that he refuses to articulate outright, is for death – maybe he DOES actually suspect that he’s quite sick, and looks forward to meeting death and getting it over with. I think you’re still left with fairly frankly erotic language that you have to contend with, though. Regardless, I think it’d be a good inclusion in a volume of gay fiction.

As weird fiction, it’s also good – the steady building dread, the inexplicableness (to the narrator) of the pale man’s actions, and even the description of the pale man himself, are all very strange and uncanny. Plus, I like the ellipsis in the ending, which can be a joke if deployed poorly, but here I think it works. Similarly, the emotional aspect of the story is richer than just simple “woooo, spooky,” you know…there’s dread, of course, but also a kind of resignation, a recognition on the narrator’s part that some sublime process is finally coming to a head. I think that’s one of the great strengths of good weird fiction, the ability to portray the complexities of the strange and the uncanny, and the way people’s lives and experiences can become tangled up in weirdness, and I think Julius Long’s “The Pale Man” is an excellent and interesting example of the genre at its best.