A real Hallowe’en treat for ya’ll today! We’re gonna be talkin’ about a tale by Frank Belknap Long that happens to have, as its main character, the great medieval poet, rakehell, and Master of Arts, François Villon! It’s Long’s short story “Men Who Walk Upon The Air!” Villon is one of my favorite poets, a real (and real interesting!) guy from the middle ages who is just this larger-than-life, enigmatic figure of fascination for me (and a lot of other people), so to have him in a weird tale! Well, it’s pretty fun!

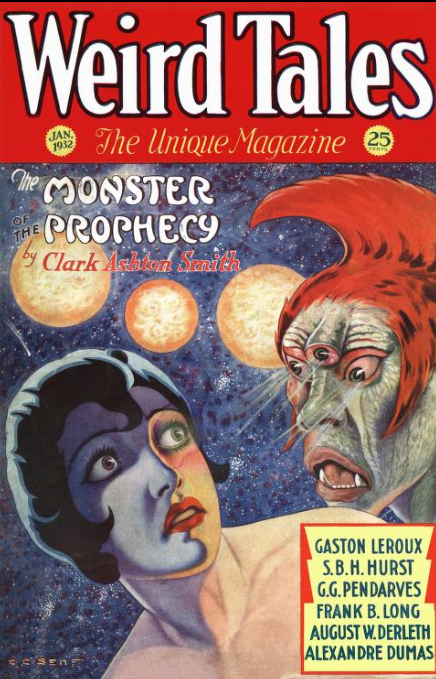

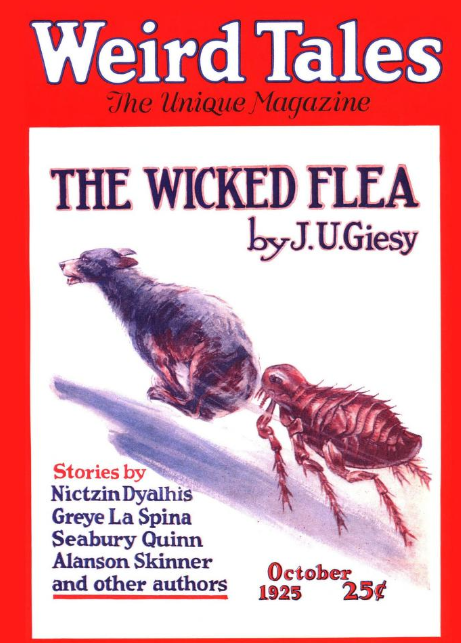

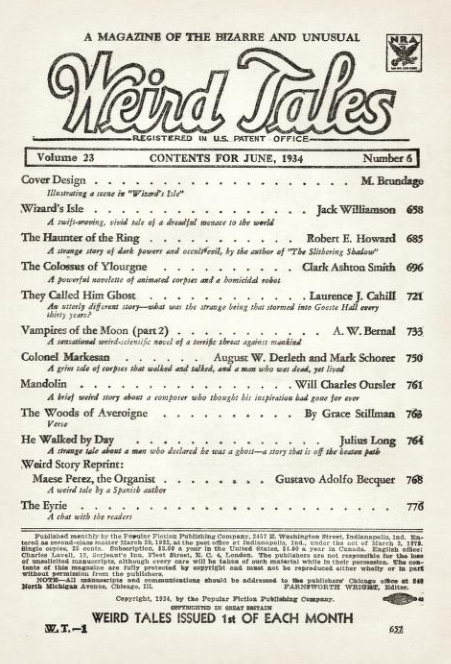

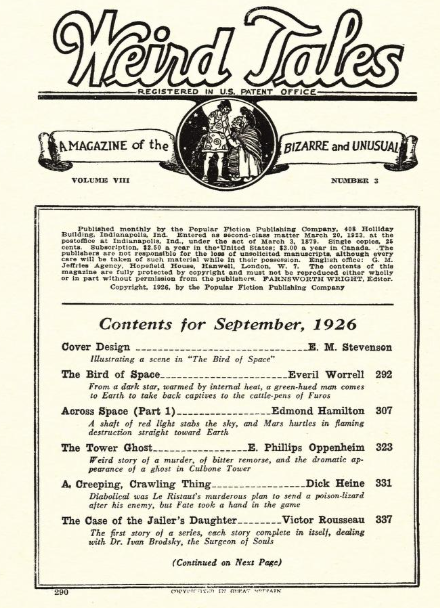

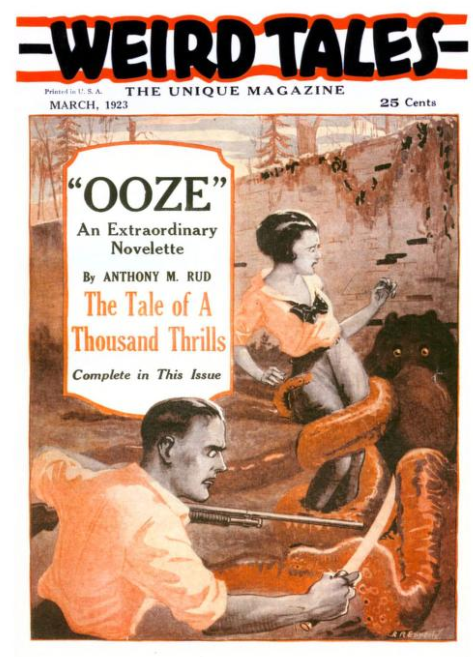

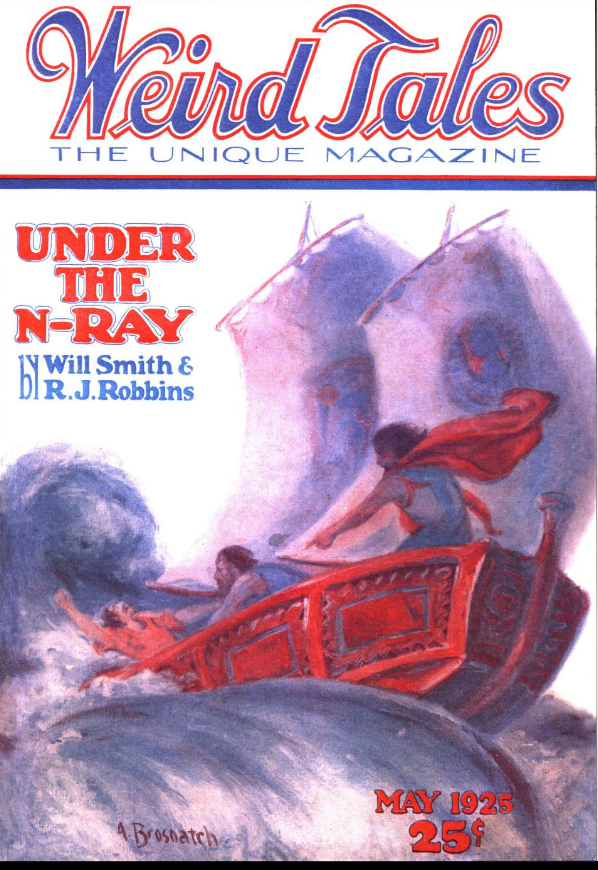

But first, the Cover and ToC of this issue!

That’s a nice adventuresome painting by Andre Brosnatch, a raging sea, full sails and a billowing cloak, excellent imagery that the story it illustrates can’t live up to, I’m sure (I don’t actually remember anything about “Under the N-Ray,” so I can’t be SURE of that, of course, but it doesn’t bode well…). Brosnatch is an interesting and somewhat enigmatic figure – he was a huge part of the early days of Weird Tales, doing a lot of good covers that always struck me as very action-y and dynamic.

Not much is known about him, though – like a lot of the pulp guys, there’s little biographical information about him. What IS clear, though, is that he definitely benefited from the reorganization in the magazine that happened in 1924 and the subsequent editorship of Farnsworth Wright. Before that, under Baird, there hadn’t been much interior art, not even for titles. After Wright came on the scene he got rid of the silly “articles” and “news items” and shit that had been used to fill up space and replaced it with art, often little atmospheric sketches and such, unrelated to the stories but very much “weird.” Things like these:

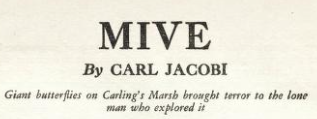

Little space fillers, but they’re fun! A LOT of these were done by Brosnatch, and would be used long after he’d stopped painting covers for Weird Tales. He was also a big contributor of the Title art at the beginning of the stories too – all in all, there was a lot more art in the magazine after Wright took over, and Brosnatch made a lot of it!

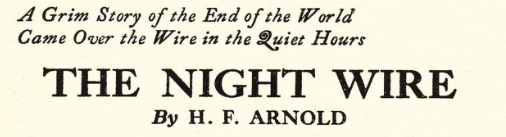

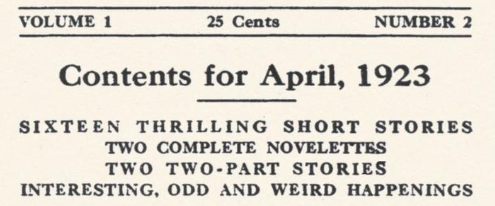

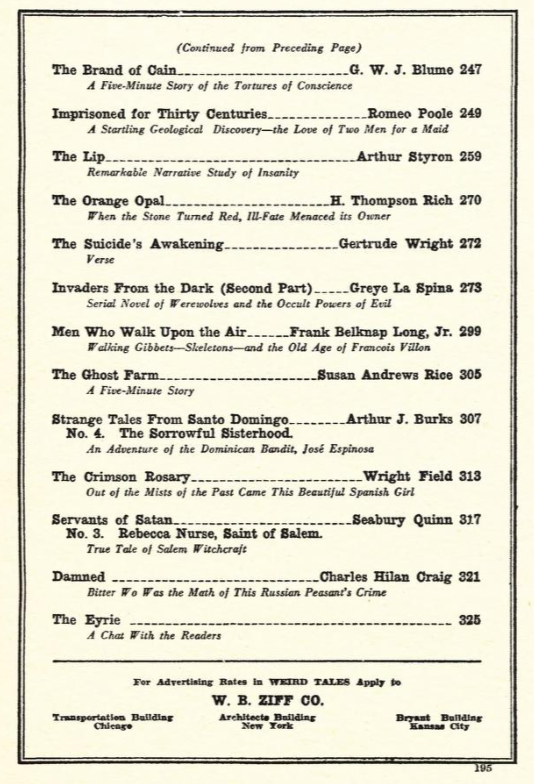

Now, a quick look at the Table o’ Contents for this issue:

Some heavy hitters this month, right? Quinn, La Spina, and ol’ Grandpa himself, H.P. Lovecraft. Actually, we might have to come back to this issue another time – the Lovecraft story this month is one of my favorites, “The Music of Erich Zann.” Nothing of Lovecraft’s can be said to be “obscure,” of course, but I do think that that story in particular is just a real strong example of weird fiction in general and Lovecraft in particular, and its not talked about or anthologized enough. So we’ll see! But we’re here to talk about Frank Belknap Long!

Frank Belknap Long was a major figure in the pulps, although he outlived them and wrote paperbacks, comics, and scripts well in the 1970s. In the Golden Era of the 20s through the 40s he wrote a lot for Weird Tales and Astounding, and he’s an important figure in horror, fantasy, and sci-fi. Undoubtedly though he was most famous as part of the Lovecraft Circle, a loose knit group of writers who, broadly, wrote weird fiction in the Lovecraftian vein. This included guys like Robert E. Howard, Clark Ashton Smith, August Derleth, Robert Bloch, all big names in weird fiction. Long and Lovecraft actually “met” in the amateur presses when a young Frank wrote a Poe pastiche that Lovecraft liked; they exchanged numerous letters and even met in person a fair amount, in New York when Lovecraft was living there, as well as in Providence and around New England when Lovecraft travelled. As an aside, the image of Lovecraft as a weird friendless loner is mostly bullshit mythologizing from long after he died; he was an avid and dedicated letter writer with a huge number of friends and acquaintances and, importantly, was very generous with praise and encouragement for writing he liked, something Long was always grateful for.

Long’s most famous story has to be his Lovecraftian “The Hounds of Tindalos;” it’s got some good, weird monsters that Lovecraft actually namechecked in his story “The Whisperer in Darkness.” He wrote other things in that cosmic weird fiction style, but he didn’t just ape Lovecraft his entire career; case in point, the story we’re talking about today, a tale of 14th century France that stars the great medieval poet François Villon!

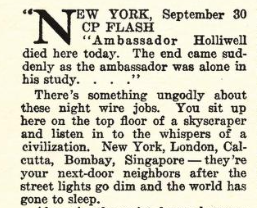

There’s that Brosnatch title art, letting you know right away what exactly the title is referring to!

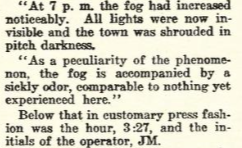

That’s a good, painterly scene portrayed right there in the first paragraph – yellow in the ditches, yellow in the sky, furtive laden figures hustling along in the evening, everything is desolate and lonely and dark. And then we meet François Villon himself, sadly regarding the gibbetted body of a man softly swinging in the night air.

The real François Villon, poet, criminal, wanderer, was born in Paris either in 1431 or 1432. He was very poor, but was raised by a stepfather who was a professor of canon law which opened doors for him. He received a Master of Arts degree from the University of Paris in 1452. He ran into the first of many major legal troubles in his life in 1455 when he killed a man in a street brawl; he only just escaped punishment through the help of his friends who had to petition the King to save him from the gallows. Then, in 1456, Villon was implicated in the robbery of the chapel of the College de Navarre. He was banished from Paris and spent the next four years as a wanderer and, possibly, a member of a gang of thieves. He’s next heard from in 1461, when he’s in jail for an unknown crime. While imprisoned, he writes his most famous work, “Le Gran Testament.” He’s released, possibly as part of a general amnesty, but again is imprisoned for theft in 1462. Villon somehow scrapes together bail, is released again, but then gets into a street brawl that sees his arrested, tortured, and condemned to be hanged, although this is commuted to banishment in January of 1463, after which he vanishes from history.

He left behind a substantial body of work, which given the time in which he lived would be enough to make him an important historical figure, but the thing is that he was ALSO a truly great poet. His poems are wry and angry and funny and sarcastic and earthy, often skewering the grand themes and pious ideals that dominated the poetry of his age. He wrote about bars and dirtbags and prostitutes and real assholes he hated, and his life and experiences fill his work; a number of his pieces are obviously autobiographical, and are full of jokes and asides and braggadocio. He played with language a lot, and put a bunch of slang and thieves’ cant into his works; he also coined a bunch of new words, which apparently makes translating him quite a challenge. Probably his most famous line is from his “Ballade” (written in jail), where he wrote “Mais où sont les neiges d’antan!” which Dante Rossetti translated as “Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!” coining and popularizing the word “yesteryear” in English. If you’re interested in his works, there’s a fairly recent good translation by Galway Kinnell for the University of New England Press titled, simply enough, “The Poems of François Villon” that’s worth checking out.

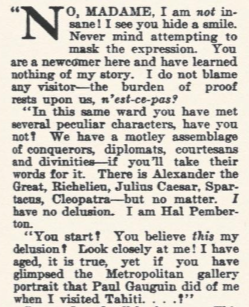

So that very real historical figure is who Long choses as his protagonist in this story. A wandering poet is, of course, a very romantic figure, perfect for an imaginative story, but right away Long does something kind of interesting:

This is certainly a figure from a medieval romance, indulging in some very poetical musings upon a hanged man, but this isn’t a young student, or even a lean weather beaten brigand-bard in exile; this is an old man, weary and worn down. He’s toothless, bald, threadbare, a figure of suffering who, perhaps, pities the dead bodies because he knows he’s nearly one himself. We’re meeting François Villon well after he’s vanished from our histories. It’s an interesting and poignant character, more so if you’re familiar with the hard life of the very real Villon.

That’s a great image, isn’t it, the gallows lonely and cold and striding across the countryside seeking warmth and companionship. There’s some very good, vital prose in this story, images and ideas that Long has really invested with a lot of doom-laden portentousness and mythic energy.

But while Villon is regarding the dead man and pitying him for his cold feet, he feels a tug at his clothes. He turns, and stares into a pair of horror-haunted blue eyes. A woman, with tears in her eyes, asks him for a favor. She drags him inexorably across the road and into a little house, where she explains: she is the hanged man’s wife, and she needs someone to climb up the gallows and cut him down. Villon, who has been admiring her beauty, readily agrees:

Villon suddenly realizes that he’s starving, and so he sits down to an insane feast.

He pigs out, making a mess as he devouring everything the woman puts on the table. It’s a strange feast though, isn’t it? I mean, rice and all those spices represent a considerable amount of wealth in the 14th century, and who the hell eats scrambled ostrich eggs, especially in a small house in rural France across from a gibbet? In particular he enjoys the ahistorical and anachronistic champagne a little too much, and becomes quite drunk. So much so that, when he totters to his feet to go and do the job he’s been contracted to do, he starts thinking that he might get another favor out of the bereaved widow.

Old man Villon sweeps her into his arms and takes more than the single kiss he’s been allotted. However, as he’s smooching her up, she suddenly throws him off and hurls herself terrified into the corner, shrieking with fright. You’ve probably guessed it; she points to the window and screams.

Villon thinks she’s nuts, at least until he hears a ghostly voice calling his name from outside the door. Terrified himself, he leaps into the corner with the woman and reminds her that his “intentions were honorable.” Then something starts straining and pushing against the door. Villon, unable to withstand the suspense, leaps up and flings the door open.

Villon stands stock still with fright, covering his eyes, trying to convince himself that the horrible revenant isn’t real. It bushes past him, running into the room and striking the wall and then, blindly begins to search the room for its wife. It’s a pretty good, horrifying scene, a blind undead monster scrabbling in the corners, feeling along the walls, hunting for you solely by touch. Shudersome stuff.

Villon watches it, horribly fascinated and feeling that he’s done nothing to deserve being put in a spot like this. Then, the corpse finds the woman, grips her with its terrible bony fingers, and then starts walking with her towards the door. Villon musters some courage to try and stop it, but gets knocked aside with casual contempt by the revenant. Collapsing with exhaustion and horror, Villon watched the undead thing drag the woman out into the night. The story ends thusly:

The horror might be a little traditional (the hanged man reuniting with his wife, one way or the other) but the weirdness isn’t, at least for me. First off, you’ve got my favorite kind of horror protagonist: some guy. Sure, this guy is François Villon, famous medieval poet, but as far as this story is concerned, he’s just Some Guy who has stumbled onto something he doesn’t understand or have any connection to. That’s a wonderful way to structure a horror story, in my opinion – an almost blank slate thrown into chaos and madness without any preparation or preamble. And Villon is good in this, he’s a tired hungry old man, down on his luck who leaps at the chance for a supper, but still a bit of a popinjay and observer of humanity for all that.

But WHO is this woman? I don’t think you can ignore the weirdness of the sumptuous, ridiculous supper. It smacks of a fairy banquet, or maybe a haunted funeral feast? It’s otherworldly and unnatural, whatever it is. And it’s made weirder by the woman’s behavior. She wants to help her husband, wants him cut down and brought inside for…what, exactly? And did she just take too long, or were Villon’s kisses to blame for making HIM come to HER? If that’s the case, why didn’t the dead husband revenge himself upon Villon? There’s a sense here that Villon is just being shown a play, some kind of shadowy undead drama that needs an audience.

I don’t know – at the end, the story just seems very moody and enigmatical, and I really enjoy it. Long has done a nice bit of weird writing here, taking what could be a pretty straightforward “corpse comes back” story and gilding it with enough mystery and description and personality that it becomes much weirder and much more interesting than you might expect! A masterful example of the weird tale, I think, worth a read this spooky season!