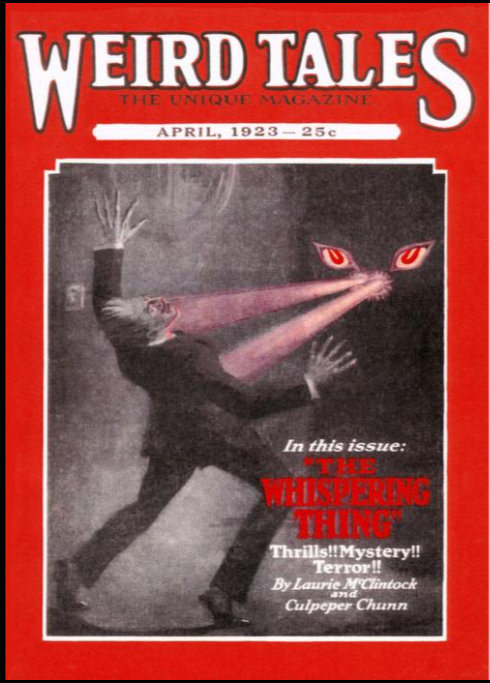

Like the merciless Juggernaut, Halloween season rolls ever onward, smooshing everything in its path beneath its powerful, unyielding spookiness. And so, to do my humble part and remind ya’ll of The Reason for The Season, here’s yet another entry in my continuing series of musings on the spook-em-ups of yesteryear. And it’s an odd one this time, too – Carl Jacobi’s “Mive” from the January 1932 issue of Weird Tales!

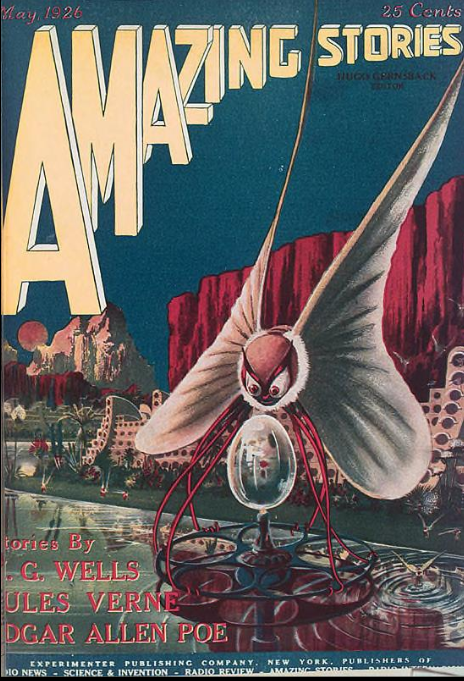

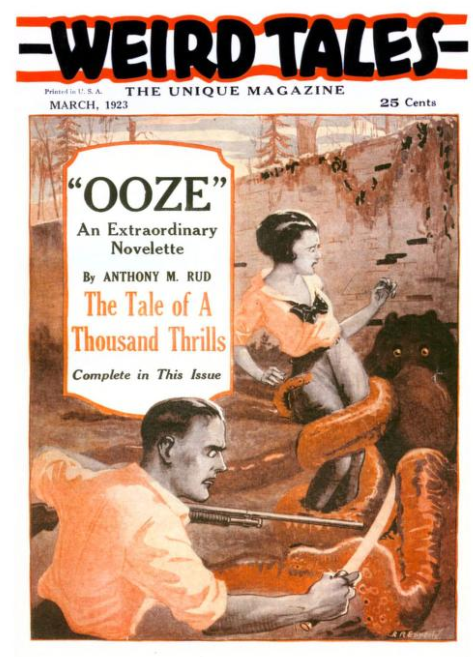

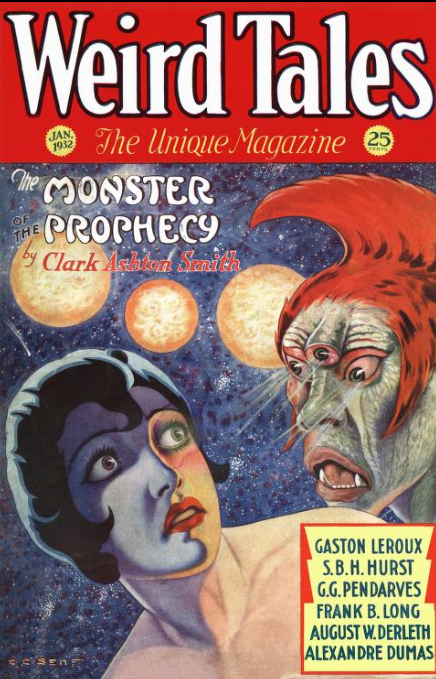

But first, as is traditional ’round these here parts, lets take a gander at the cover of this issue! And lucky for us, it’s a C.C. Senf classic!

I think last time I said I wasn’t sure if ol’ Clark Ashton Smith had ever had a cover and, well, by god, here it is! And by Senf, no less, one of my favorites of the early Weird Tales cover artists. Curtis Charles Senf did a pretty good number of the early covers for the magazine, a couple dozen at least, plus a lot of great interior art too. This is one of his last, though – I think he has a few more in 1932, but after that he goes on back to commercial illustration work, which I think you can see he clearly had a talent for. I like his style a lot; expressive faces, flapper haircut, weird-ass monster, trippy space background. It’s good! Wild thing is, it has pretty much nothing to do with the story, which is a very goofy space fantasy tale about a suicidal male poet who travels to an alien world, helps foment a revolution, and then makes it with a five-armed space empress babe. It’s not my favorite Smith, by a longshot, but it does have a lot of implied sex, so there’s that.

Of course, a lot of the covers had fuck all to do with the contents; it was practically a requirement! Still, I think the Senf image illustrates nicely one of the biggest draws that pulps had going for them – the cover art is honestly something, often dynamic and a little lurid, really something that grabs your eye! I harp on about how the pulp era was the golden age of the short story, when people could make a living writing fiction AND when millions of people got their entertainment by reading it, but I bet there’s a similar story in illustration – there were so many more markets for your work, and a huge number of people exposed to it too! A heroic age, never to be seen again, sadly.

Ah well, such is the turning of the wheel, huh? Anyway, here’s the ToC:

Smith, Pendarves, Derleth, Long, Wandrei – it’s a veritable Who’s-Who of Big Names That Few Now Would Recognize! All of them were fairly major Weird Tales authors; G.G. Pendarves in particular was very popular, and it wasn’t until her death in ’38 that Farnsworth Wright revealed in an obituary that her real name had been “Gladys Gordon.” Again – the pulps offered a chance for people who might otherwise have been stopped at the door to slip in and get their writing published and read!

Our author today, Carl Jacobi, was a prolific and long-lived writer of fiction, with a good number of stories in Weird Tales over his career. His style is good, a little florid for us today but nowhere near as elaborate or languorous as Smith or Lovecraft, for instance – in fact, if you compared his work to others at the time, you’d probably say it was rather fast-paced and propulsive! His work has been anthologized a lot over the years; he’s got a good sense of the creepy and the atmospheric, as well as a real imaginative streak, as we’ll see in today’s fairy short story, “Mive.”

That’s right! It’s a Big Bug story!

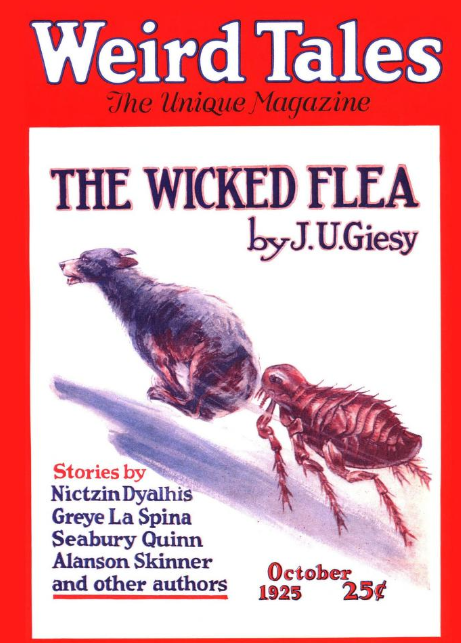

Bug fiction, of course, has an important place in the history of outre imaginative fiction; there’s Wells and his ants, and Lafcadio Hearn wrote numerous essays on the cultural and folkloric significance of insects in Japan. Within Weird Tales there’s a kind of interesting history, though, so I hope you’ll pardon a brief digression. In 1925, a few short years into Weird Tale‘s existence, they published a story by J.U. Giesy titled “The Wicked Flea.” Now, if you know yer bible, you might recognize that as a punning take on that old chesnut from Proverbs: “The wicked flee where no man pursueth.” Now, that’s bad enough, but take a quick peek at the cover of that issue:

A dog!? being chased!? BY A BIG FLEA!? Why the whole idea is PREPOSTEROUS!? What an amusing reversal!!!!

That’s right: it’s a COMEDY story.

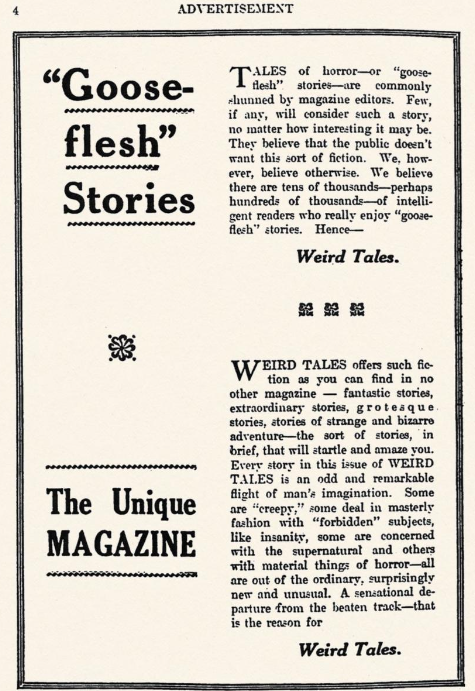

What’s that? You’re asking how the Weird Tales audience received it? Readers, they hated it. Huge number of letters to The Eyrie where they begged Wright to never publish anything like it. A consensus soon built, and basically humor stories of all stripes were banned from the pages of Weird Tales forever. I feel like that actually had a huge effect of the development of the weird tale, too – there’s a deadly seriousness that descended on the genre and never really lifted, so much so that a lot of readers lost their ability to see the often slyly humorous parts of many stories, I think. For instance, when Lovecraft’s “Herbert West – Reanimator” was posthumously published in Weird Tales, a lot of people didn’t recognize that the constant over-the-top joking going on. Oh well!

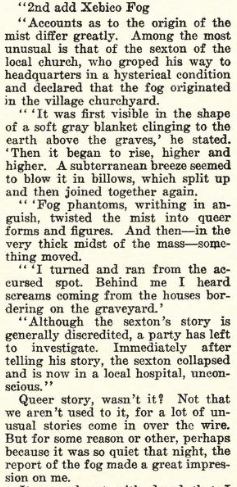

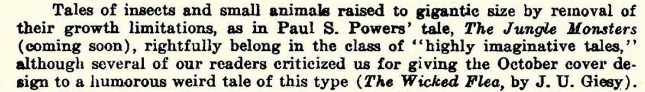

Anyway, the upswing of it was that, following the furor over the goofy story, Wright kind of summed up the state of the genre in an editorial in The Eyrie in the December 1925 issue, trying to clarify what belonged in Weird Tales and what didn’t. Here’s what he wrote about Big Bug stories:

I dunno, I find this kind of stuff fascinating; the way Wright, in conjunction with an active and participatory fandom, are negotiating and mediating what is and isn’t weird fiction…it’s cool stuff! But on to “Mive!”

A kind of moody meditation on both wilderness and the way people perceive it – it’s a fun way to start a piece of pulp weird fiction, I think. The sublimity of the environment is a rich vein of weirdness that’s not mined often enough, for my tastes. Actually, this whole beginning, nearly a page, reminds me strongly of Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows,” with its preoccupation with human interlopers in a wilderness setting; there’s a similar sense of the strange and inhuman atmosphere of this place, evoked by the description of its riotous plant life, its strange geography, AND by the fact that it’s got these really weird names. “Mive” is an odd one…sounds like one of those old, inexplicable celtic/saxon/welsh hold over names you run across in England, you know what I mean? Like it must have some meaning, but it’s just utterly lost to you, now. Similarly, the oddity of a cypress hammock called “the Flan” is notable…right off the bat there’s a real sense of disorientation produced by Jacobi here, really nicely done bit o’ weird fiction writing!

Quick note: “Rentharpian” is a funny word, but it just refers to Jacobi’s own version of “Lovecraft Country.” He mentions a “University of Rentharp” in another story, so it’s like the Miskatonic Valley and Arkham and all that, a generalized fictional location somewhere in the United States that gently connects his stories together. Absolutely love it, one of the best parts of weird fiction in my opinion!

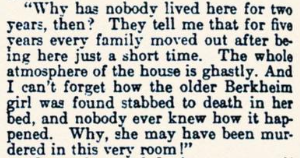

Most people stay away from the Mive, but our narrator has submitted to his particular imp of the perverse and gone for a walk along a disused road that leads along side of the marsh. He reaches the swampy stretch where, for some reason, he’s drawn to the wilderness and plunges headlong into the green hell.

More excellent environmental writing, partaking of that peculiarly White Euro-American horror at the rampant fecundity of nature. This is something right out of 19th century tropical travel narratives, a kind of revulsion at just how furiously ALIVE a forest or a jungle or a swamp can be. Another noticeable undercurrent exists in both that genre of writing AND in our story here: the alienation an animal experiences in a place dominated by plants. In fact, here, in the Mive, the narrator notices the absence of all the usual swamp critters…until…

A Big Ass Bug! Kind of an uncalled-for burn on proboscises, though – it’s just a curly cue tongue man! What? Your gustatory apparatus is so much prettier and cooler? Jeez.

Operating under a kind of strange compulsion, the narrator grabs for the gigantic butterfly, but he succeeds only in getting a strange, powdery dust from its wings on his hands. Annoyed, he tries to brush it off, but the sweat from his hands has made it sticky and gooey and damn if it don’t smell good too!

Well, he fights it off as long as he can, but then sticks his fingers in his mouth, and is immediately struck by the foul, bitter taste, nothing at all like the sweet alluring scent. He coughs and sputters and is disgusted at himself; then he gets doubly annoyed because he didn’t catch the giant butterfly and so no one is going to believe that it exists. He decides it’s time to head home. But…

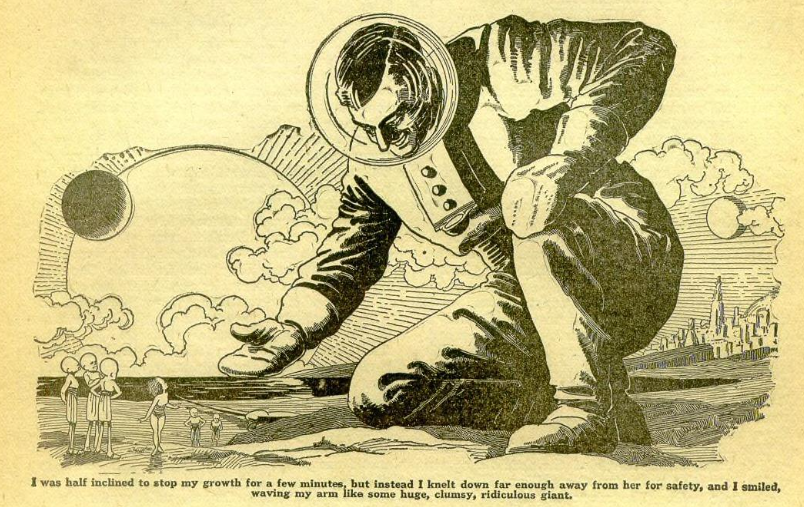

A human-sized cocoon, and it’s hatched too! Makes the previous butterfly seem positively rinky-dink in comparison! And, of course, there’s also the perfectly logical deduction that a big fuckin’ butterfly must’ve evolved carnivory and that’s why the swamp has been denuded of vertebrate life! Our narrator grabs a stick and, feeling a little nauseous, starts trudging his way home. A storm builds overhead, black clouds billowing to darken the sky…but IS it a storm?

What the fuck, right!? The clouds solidify into some kind of strange, phantasmagoric scene of a medieval city and an army in full retreat from a horde of the black-winged giant butterflies! The defenders fall and the whole city is swallowed by the roiling swarm. Then, the scene dissolved into more chaos, eventually coalescing into the form of a singularly huge butterfly, its vast wings filling the sky.

He turns and flees, crashing through the underbrush, squelching through the mud, trying to escape the horrendous vision he’s seen. The forest itself becomes monstrous, the reeds and grasses gripping him, slashing at his arms and legs, all of nature turned into a hellish, predatory monster that seeks to devour him. A storm fills the sky, and the waters of the Mive turn black and oily. Then, a giant butterfly descends from the blackness overhead, pursuing him!

He hides in the underbrush and it misses him; in a mad chase he flees the swamp, eventually reaching the road and collapsing with relief as the storm breaks and rain washes over him. What happened!? You’ve probably guessed, but let’s see what our narrator figures out:

Hallucinatory butterfly dust! Of course! What master insect indeed!

That’s the end. It’s short and to the point, a fairly simple series of events overlain by some weird hallucinatory imagery and descriptions. What I like about it is the way Jacobi approaches a world where people and, indeed, vertebrates, are superfluous interlopers. From other stories of his, I know Jacobi had an interest in geology and paleontology, particularly with regards to early Paleozoic stuff, so this vision of a primal swamp with giant insects seems positively Silurian, a vision of the world 420 million years ago. A geological perspective is, I’ve argued before, one of the main scientific ideas behind weird fiction – Deep Time’s dehumanizing and, indeed, de-mammalizing, perspective forces us to confront a universe that is perfectly happy with other orders of being and types of life. For Lovecraft and Howard and them, this is often oceanic or reptilian life, but here Jacobi has latched onto a vision of life that is botanical and insectoid, both truly strange and alien organisms, at least in comparison to our own particular clade.

The strange vision of a medieval cloud city destroyed by butterflies, as well as being just plain weird, also reinforces this idea, I think – the world of humans, with its projects and monuments and struggles, is just one ephemeral version of life on this planet. The contrast between the perceived fragility of a butterfly and the assumed solidity of a vast walled fortress full of mailed warriors is interesting in its juxtaposition, especially since both prove false – the triumph of the strange butterflies over the “superior” humans is of course a classic weird fiction inversion, but it also resonates with how easily our narrator is overcome by the hallucinatory dust. He’s immediately undone by a big ol’ butterfly, and is powerless in the face of this totally unexpected threat!

It might be a little predictable; I think once the wing dust is mentioned, you’re primed for something like this to happen, especially when he fuckin’ eats it. But for all that, I think it rises above the kind of trite “woah, what a trip!” sort of thing it might’ve become. Jacobi is interested in how people and nature intersect, and the ways the assumed roles of big critters like us might be upended totally. A fun story with a decidedly weird point of view!