It finally cooled down here in Texas (where I live), and with those open windows and brisk overnights in the mid-60s, I’ve finally begun to get all spooked up fer Halloween season! As such, I’m going to be super indulgent in these pulp strainers for this month, picking stories based not on their importance or significance, but rather on how much I like ’em! And we’re going to start with what is certainly one of my personal favorite weird tales of all time, H.F. Arnold’s absolutely incredible “The Night-Wire,” from the September 1926 issue of Weird Tales magazine.

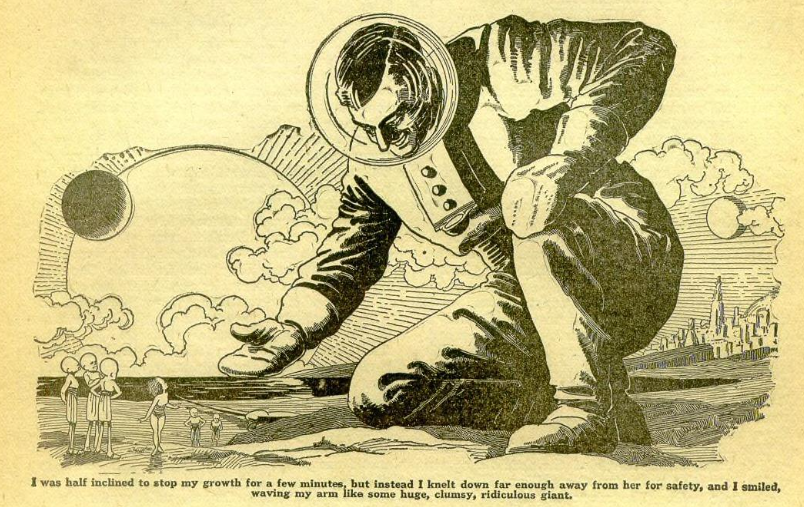

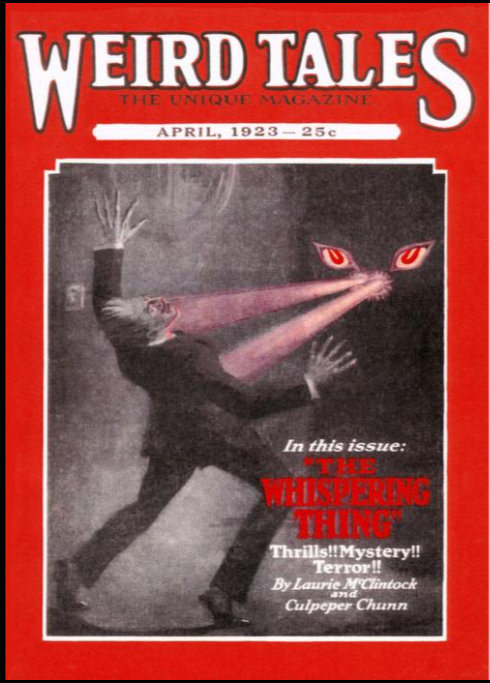

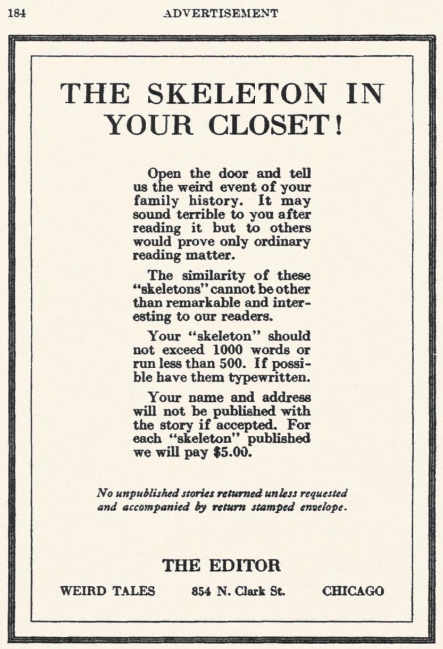

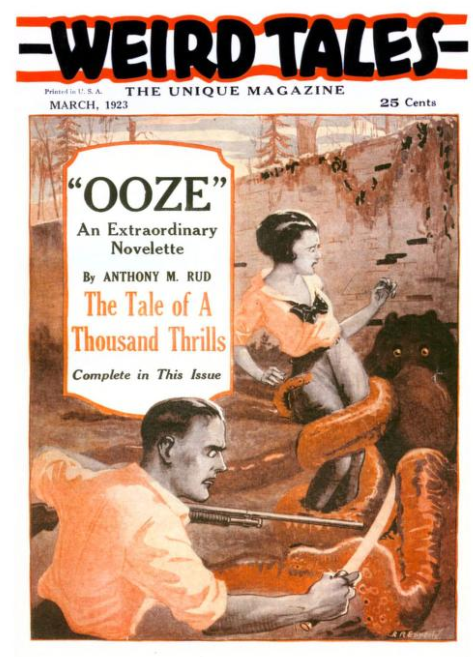

The cover by E.M. Stevenson for this issue of Weird Tales is pretty underwhelming, in my opinion; Stevenson had done a number of covers for the magazine, probably most famously illustrating Robert E. Howard’s first appearance on the cover of the magazine, “Wolfshead.” His style isn’t my favorite, but even so the weakness of this cover probably has more to do with the fact that, other than Arnold’s “The Night-Wire,” this is a pretty lackluster issue.

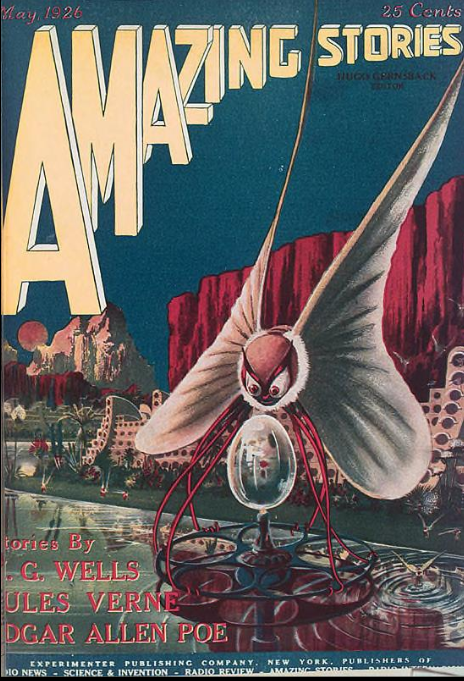

The Quinn and La Spina stories are nothing like their strongest, and the story they gave the cover to, “The Bird of Space,” is one of the “pseudo-science” stories that would rapidly vanish from Weird Tales, migrating over to the newly invented “science fiction” magazines (fyi, Amazing Stories had only begun publishing this very year, in March 1926; before that, a lot of “planet stories” had had nowhere else to go but Weird Tales). Even the Lovecraft story in this issue, “He,” is really dull, one of his “goddamn I hate living in New York with all these non-WASPs” stories that is just a real slog to get through (although it’s got a good monster at the end). But! There is a single gem in this issue, and it is “The Night-Wire,” an absolutely incredible story by the mysterious and unknown H.F. Arnold.

First off, who the hell is H.F. Arnold, anyway? Well, to cut the chase: we don’t know. He published two stories in Weird Tales, this one in 1926 and a sci-fi two-parter in 1929 titled “The City of the Iron Cubes;” then, in 1937, he presumably also published a two-part sci-fi story in Amazing Stories titled “When Atlantis Was.” I say “presumably” because that’s one hell of a gap, and it’s not like the name is particularly notable or unique. There are some articles, one about cowgirls and one about “loco weed” that were written by a “Henry Arnold” and published in some western pulps in the 20s too, and depending on who is doin’ the writing, these are sometimes attributed to him (though just as often not). But that’s about it! No confirmed birthdate or death date, no bio, no job, no nuthin’! A few years back some folks thought they’d identified him as an Angeleno, but then I’ve seen other people dispute it. On the basis of this story, “The Night-Wire,” some people suggest that he must’ve been a newsman or have worked in a radio news office, but that’s pure conjecture. Just another illustration of Harlan Ellison’s point about the pulps: we don’t know anything about a huge number of the people who wrote em!

But, despite H.F. Arnold’s scant output, they produced at least one masterpiece in their mysterious lifetime. “The Night-Wire” is so good that I want to stress that if you haven’t read it, take the time now and go read it. Here, I’ll even link it again for you, right here. Seriously, don’t deprive yourself of the pleasure of encountering this story blind and unsuspecting, it’s worth it. Plus it’s real short. Just go read it, okay?

Alright, assuming everyone has read it now, let’s dive into:

No illustration for this one, sadly – can’t imagine why, the thing seems tailormade for weird imagery! But, oh well! Here’s how it starts:

The news flash right up front is a nice touch, a good contrast with the kind of hard-boiled narration that comes after, and both really set the scene. Immediately you get a sense of isolation, clacking machines, radio beeps and whatnot, a lonely guy sitting waaaaay up atop a concrete and steel needle in the dark, communicating with distant offices via the strange sorcery of radio waves. It’s great! it’s economical! Can’t be beat. Also, interestingly: is the “CP” part, mentioned there, the Canadian Press? Or is it meant to be a generic version of the AP? I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter – it’s just the signifier for the press releases being transmitted.

Our nameless narrator spends a little bit more time musing on the strangeness of being a wire man at night, giving us a sense of the job. This part is a lot of fun for me; I’m honestly a sucker for technical jargon and expertise, especially when it’s done in the pulps like this. There’s something fun about the image of some guy, cigarette wearily clamped in his teeth, methodically going about his work. This idea of someone whose damned good at their job is also something on H.F. Arnold’s mind, because he soon introduces us to the narrator’s companion there at the wire desk, John Morgan, a “double” man who, strangely, can apparently listen to AND transcribe TWO separate news feeds on TWO separate typewriters SIMULTANEOUSLY! Was that ever actually real, I wonder? In the story, Morgan is one of three operators the narrator has known who can perform this bizarre miracle. I have to floss looking away from a mirror I get so turned around, so the idea of someone transcribing two different news reports on two different typewriters boggles my poor clumsy mind.

It’s a quiet night there in the office, so the narrator is surprised when Morgan switches in the second wire and starts banging away on the second typewriter. He gets up and checks on the pile of typed copy for this new, second wire. And what does he see?

Just right off the bat, the name of this town is really good. There’s a nice, outre euphoniousness to “Xebico” in my opinion; you’ve got an X there, of course, right away that’s plenty weird, but then there’s a kind of indeterminant exoticism to the rest of the name, a vaguely Latinate suffix in the -ico ending that suggest something familiar, but you can’t place it. It’s a peach of a name for a weird city, is my point. And what’s shakin’ in ol’ Xeb town tonight?

Bit o’ fog is all – nothing strange so far, although “scientists” being unable to agree on its origins is neat (fun to imagine them asking, like, a coleopterist and a structural geologist and solid-state physics guy about this fog). The only thing that stands out to the narrator is the weird name for a city he’s never heard of, which is strange to him – as established in the beginning, wire guys get familiar with all these distant, strange places, so running into some place new is a pretty rare occurrence.

At this point in the story, there’s nothing overtly odd going on, although I think Arnold has done a great job laying the ground work; there’s the weird name, sure, but then there’s also the weird “double” typing of Morgan that stands out. It’s a real strange image, isn’t it? Some guy plugging away on two typewriters at once – very reminiscent of automatic writing or, even more occultly, channeled writing being done in a séance. And, as the story progresses, I think we’ll see that that was exactly what Arnold was trying to convey.

Fifteen minutes pass, and Morgan produces more copy:

And more:

It’s a great little escalation, and feels very cinematic, doesn’t it? This strange fog has appeared, no one knows where it comes from, “scientists” can’t come to any consensus…and now some weird guy from the church shows up, screaming about writhing phantoms and the way this unearthly miasma has boiled up from a graveyard. Of course you can’t believe him, he’s hysterical, but maybe we oughta send some folks over there to check it out, just to be sure…

There’s very little narrator interjection, just the guy acknowledging that, yeesh, that’s some weird stuff coming out of Morgan’s typewriter, huh? Spooky on a lonely old night like this, too. It’s all just really great writing, clean and efficient and evocative.

That escalating tension continues, with further stories from Xebico telling how the first search party that was sent out never returned, so a second, larger party was dispatched to figure out what the hell was going on. (I’m sure that’ll work out fine!) Meanwhile, further chaos is engulfing Xebico – families are abandoning their homes and flooding into churches, fearfully praying for salvation, while the fog grows ever thicker. Good stuff! Very atmospheric, and the added layer of hearing about it second-hand, via the narrator’s reading of the wire copy, provides so much to an atmosphere of disconnection; where the hell even is this place, and what the hell is happening there!?

And meanwhile Morgan keeps on transcribing, slumped and strangely still in his chair, the keys clacking monotonously in the quiet office. Fascinated and horrified, the narrator reads over his shoulder.

The image of that is pretty fantastic, isn’t it? Reading what comes next, word by word – it’s very spooky, and you get a sense of real tension as you imagine them coming in, letter by letter, from Morgan’s typing. And what comes in is some pretty wild stuff!

The inexplicable apocalypse only gets weirder from there! The reporter sending the transmission sees the fog part, briefly, and witnesses true horror – the dead and dying bodies of Xebico’s citizens appear, but they’re accompanied by…something else…

The final transmission from the reporter gets a little psychedelic; strange fiery lights of a mysterious and impossible hue fill the sky and seem to pour down into the city. There, some kind of strange transfiguration occurs; is the light somehow a second phase of this disaster, or is it combatting the fog? We never know, because Xebico goes silent, forever. And then, back in the tower, the denouement:

First off, the second wire hasn’t been receiving anything at all! And, stranger still, Morgan has been dead for hours. What, then, was the Xebico transmission? The dying impulses of Morgan’s brain? An etheric communication from somewhere beyond? Thankfully, H.F. Arnold doesn’t tell us, letting the mystery just sit there, like a toad.

Obviously, I love this story – it’s got everything I like in a weird tale, and it does it all so artfully and elegantly that you can’t help but get drawn in. Everything about it is strange and different and just not-quite-right. The technological aspect is interesting: invisible waves travelling thousands of miles to brings information to people, who sit in the dark and scribble it down. It’s modern radio presented in a very gothic style, with the wire men like monks pounding away on their manuscripts. And then the image of Morgan as medium (and a dead one at that!) receiving, in a more visceral and mystical way, a transmission from somewhere else. And then, what the hell is going on in Xebico, anyway? Murder fogs full of strange phantoms, weird lights in the sky?

I guess that’s all I have to say about it. Fer my money, it’s one of the best stories Weird Tales ever published, perfectly spooky and strange. If you’re looking for something fun to read this Halloween season, I’ll once again urge you to check it out!