A very merry Solstice to you and yours! On this, the darkest day of the year, let us enjoy some deep, indulgent fiction, the work of an author who was an important antecedent to Sword-and-Sorcery, the rich and evocative Clark Ashton Smith! Today’s story is maybe my favorite thing he ever wrote: The Abominations of Yondo, originally published in the April 1926 issue of the Overland Monthly!

For some reason or another, this S&Smas I’ve been focusing on the genre after Howard’s death; this has included a story by the great Fritz Leiber and the not-so-great but still interesting work of Henry Kuttner and Clifford Ball. Important points in the genre’s evolution all, of course, but no genre springs ab nihlio! There’s stuff before it, points of reference or experimentation that are pushing at (or solidifying) boundaries! And while I do think Howard’s work is uniquely important and an epochal invention, he was but part of a milieu that was exploring the newly created genre of Weird Fiction. Clark Ashton Smith was an important figure in that group, helping to define the aesthetic and move the genre in new and interesting directions, an important bridge between pre-genre writers like Dunsany and Howard’s eventual creation of Sword-and-Sorcery.

Which is not to say that this story in particular was a key influence on anything; hell, I’m not even sure that Howard ever read this one. It’s entirely possible he did – he and Smith were correspondents, of course, and there’s a chance he got a copy from him or HPL or something like that, but I don’t have any evidence at hand about that (remember – I’m writing these things off-the-cuff and straight-from-the-hip, with no time for looking things up in the multi-volume letter collections of these people). Like I said up top, this is just one of my favorite of Smith’s, and I’m allowed to indulge myself every now and then! BUT I do think this story is incredibly illustrative of one of the very important parts of both the creation of weird fiction AND the sub-genre that would come to be S&S, which we’ll get to later.

Now, you’ll also note that this story is not, per se, from a pulp…it’s from what was very much a storied literary magazine, The Overland Monthly, a magazine founded in the 1860s to advance the literary culture of the West broadly and California in particular. It included famous writers as Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, and Willa Cather, and ALSO published work by early nature writing by people like Muir and the famous geologist Clarence King, which makes Smith’s bonkers little story an interesting addition to its body of work. I think there’s plenty of reasons for why it was published here, HOWEVER it is important to note that “The Abominations of Yondo” was originally submitted to Weird Tales, representing as it did Smith’s first foray into weird fic. Farnsworth Wright rejected it, doubtless because it’s not really a “story” as such. Which is fair! This is, as I hope you’ll see when you read it (it’s quite short!) very much more of a vignette, moody and evocative (and trippy) but without much of a plot or character. Doesn’t mean it’s not rad as hell, of course, and I’m sure Wright liked it – it just wasn’t a comfortable fit as a story. So, while “The Abominations of Yondo” ended up in a high-falutin’ hoity-toity literature mag, it was absolutely and unequivocally written within the tradition of the weird tale as created in the magazine, Weird Tales. Also, it’s Clark Ashton Smith, gimme a break! He’s one of the Big Three! It counts!

Anyway, let’s dive in:

Much like Weird Tales, you can see that this magazine was not cheap! Twenty-five cents in 1926 was no joke – that’s like $5 now, a decently priced bit o’ culture! It’s also very clearly positioning itself as a Western magazine of culture and literature too, isn’t it, a very solemn bit of romantic appropriation on its cover and all. As for the ToC:

You can see George Sterling, CAS’s mentor and friend, is on here too, both as a contributor AND as an editor (explaining how “Yondo” endued up here, in part). But the best part, in my opinion, is the brief little author’s bios on the side. Take a closer at Smith’s:

I mean, that’s pretty funny, isn’t it? Smith is absolutely a California Poet, of course; this story today is only his third piece of prose ever published, and his first bit of outré fiction too. Prior to that he’d had several collections of his poetry collected, so this IS the beginning of a new phase for him, artistically (and economically – he took to weird fic largely as a way to make money). But it’s also a fun, oblique way to acknowledge that this is a bit of a departure content-wise for ol’ Overland Monthly.

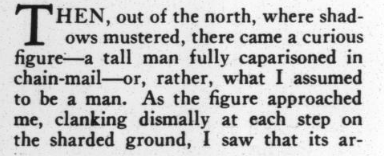

You can tell this is a Serious Magazine because there’s no art. No buxom ladies being menaced here, no sirree, just cold hard text!

Smith is even more purple and rich than Lovecraft, but I’ll be goddamned if it doesn’t work! His background as a romantic poet, and particularly someone interested in the decadents, really shows through in his over-the-top, hyperbolic language, but (like Lovecraft) he comes by it honestly – there’s no affectation here, it’s all a deeply considered and hard-wrung aesthetic that he’s employing, one which is sumptuous and suggestive and decadent, and it works! Come on! Yondo (which we learn immediately is a place, which means that the title is about Abominations in Yondo, or perhaps from there) is a desert on the edge of reality, covered in the dust and ash of dead planets and rotting suns. I love the orb-like mountains, which Smith tells us are asteroids plunked down in the sands, a wonderfully outre image. Also wonderful is the menace and terror of the fact that this borderland on the edge of the world is open to incursions from all sorts of things from Outside, a wonderful bit of Lovecraftian horror derived from discussions and readings of HPLs work with the Old Gent himself.

Great, smoothly efficient introduction of both the narrator and the world we’re reading about. Our nameless dude, a heretic, has been tortured by the Inquisitors of the Lion-Headed Ong and, his punishment done, he’s been “freed” on the edge of the vast, hellish wilderness of Yondo. There’s great descriptions of both cacti- and fungi-forests (suggesting a very strange hydrologic regime at work here), and wonderful landscape writing too, lichen-mottled soils and grimy tarns, all evocative of real, hostile, untouched wilderness.

We get very sparse background on our heretic – he pissed off the Priests and Magicians of Ong, and as punishment he faced tortures both physical (stretched on adamant-dusted dragon-gut racks) and psychological (oublietted in a dark hole with huge fat corpse worms dropping in on him). But, eventually, they finish with him:

Now, we’re told that Yondo is a terrifying, mysterious, and all together evil place – very few people have gone there, and even fewer have returned. Those who have? Driven mad of course, palsied with the horrors they encountered there! Fantastic stuff! And our guy is a little trepidatious about entering Yondo…but what else can he do? So, ignoring the horrible insects that seem to be following him, he marches into the Wastes of Yondo, hoping to get through it and fall in with some nomads who live on its northern borders.

Again, wonderful weird landscape writing here. Smith is highlighting the sheer alienness of this landscape, and also wants us to think about its vast, incomprehensible age, and the way time has ground down whole civilizations:

The “fat chameleons” creeping with “royal pearls” in there mouths are nice inversions of the “dragons with pearls” motifs of a Chinese imperial art, and the endless ruins given over to hyenas and snakes makes for a wonderfully rich sense of decay and collapse. Also, great geology terms, even if they are extremely archaic – no one has used psammite for sandstone (or, possibly, metamorphic rock with a sand rich protolith) since the 1850s, man! Porphyry is also a rock name freighted with meaning – “imperial porphyry” was the term for the rock used in a lot of Pharaonic monuments.

Our heretic spots a bitter lake fringed with salt bars below him, and hustles down for a refreshing dip…unfortunately the water stings his hand, and he realizes this puddle is the last remnants of a sea! And ideal picnic spot! He sits down and rests, eating some bread and sipping some water, gathering his strength.

Man, c’mon…the MINUTE you start thinking like that, you KNOW some shit is going to go down!

Told ya, dummy!

The unearthly chuckling (like the “mirth of an idiotic demon”) goes on and on, and out heretic realizes its coming from the speleothem-fanged mouth of a cave he hadn’t noticed before.

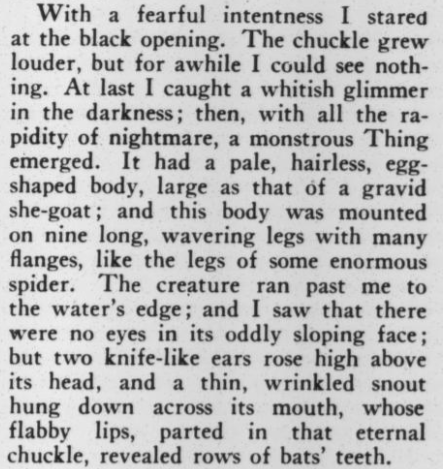

I mean THAT’S a damn monster, isn’t it? Pale, hairless, egg-shaped body, NINE goddamn legs, but fer my money the weirdest thing is the things Bat-ness, a hint of Smith’s horrible elder god Tsathoggua, maybe? Like both HPL (sea-life/fungi) and REH (reptiles but especially snakes), CAS often uses bats (or a furry bat-ishness) as a kind of signifier of deep, outer evil. I love the thing’s blindness, and the suggestion that the thing’s “eternal chuckle” might be some kind of echolocation. But the Big Fella is just thirsty!

He runs as far and as long as he can until, exhausted, he reaches a boulder field in a vast sandy sea. But he doesn’t get much of a chance to rest:

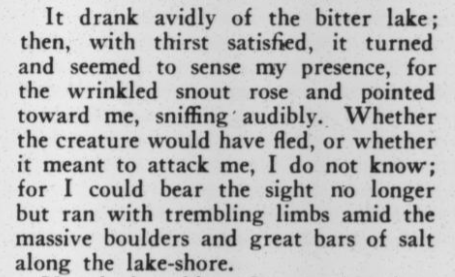

The fuck is going on here!? Some kind of figure screaming in horror, but when he approaches it, it becomes a statue, the terror-widened eyes now closed, the outstretched plaintive hands now hidden in the sand…extremely, beautifully weird stuff! Of course he runs, and takes particular care NOT to look back behind him when he hears the terror-filled shriek again.

He runs deeper into Yondo, but eventually notices that he’s picked up a strange shadow that is keeping pace with his own! It’s an odd, inhuman shape, this second shadow, with an elongated head and maybe five limbs, but it is also relentless, neither gaining nor losing ground, but always following him as he runs into the wastes.

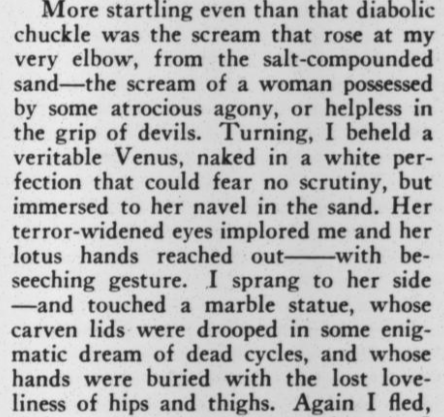

I love it! The smell building around him as the pursuit continues, the fact that he (and we) have no idea what this thing is – is it a monster invisible save for its shadow, or is it some of shadow monster? Is the threat physical or spiritual? What will happen if the shadow CATCHES his shadow? It’s great, scary stuff never answered, and even its eventual departure is menacing and weird:

He waits in the weird circle, exhausted and terrified, but eventually he rises. Night is threatening, but he has to go on – his only hope is to push on northward. If he can get to the border country he can leave this unearthly place behind him…but that’s a helluva “if!” He gets up and heads out! The powdered dust of millennia-dead civilizations makes for pretty sunsets, apparently: the horizon is ablaze with miasmal scarlet, lending the already bizarre landscape of Yondo a particularly phantasmagoric cast. And then:

Very Nazgûl-ly, huh? Faceless, with an empty helmet and ancient rotting armor, apparently just going out for a walk. I love the way it clanks “dismally” as it goes, too, a wonderful bit of description. But our heretic can’t spend much time considering this Witch King of Angmar lookin’ motherfucker, because there’s a second, even more horrible apparition!

A perfect monster, in my opinion – a huge figure, the monstrous mummy of some ancient king, and the way he describes its face as being ruined by MORE than time or the worm is wonderful. What the fuck is this thing! And then it’s got another little monster in its crown! The way the ape-headed serpent thing is introduced as first a shape, only for its eyes to open and reveal it as another being, is perfectly done, a flawless bit of weird writing. And then it whispers in the giant lich’s ear! It’s so horrible! And then, like in a nightmare, the huge mummy closes the distance between them SUDDENLY, reaching out for the heretic’s throat!

And that’s the end of “The Abominations of Yondo!”

The Inquisitors waiting for him, knowing that he’ll be back, is great; this whole ridiculous thing has been another bit of psychological torture, something straight from Orwell’s Room 101. Smith’s stories often have a sadistic streak to them, sometimes too much so, but here it’s the perfect capper to this little fable, a real nice bit o’ meanness on top of the weird monsters and landscape of Yondo.

In addition to this being full of great monsters, it’s also an important bit of fantasy-flavored weird fiction, very much part and parcel with Lovecraft’s Sarnath or the Cats of Ulthar; while Lovecraft would leave that sort of writing behind him in a year or two, Smith would keep it alive, pushing the boundaries of weird fantasy with his Hyperborean stories or his Zothique tales. I also think this is a fun one because it’s got some fun hints of things to come – the bat monster, the second shadow, the horrible liches. There’re some fun “first draft” kinds of things in here, Smith finding ideas that he would polish and refine over time in its writing.

Maybe more importantly, though, and the real valuable thing in this story, is what it illustrates about one (of the many) underappreciated parts of Sword & Sorcery – namely, S&S as a literature of landscape and environment!

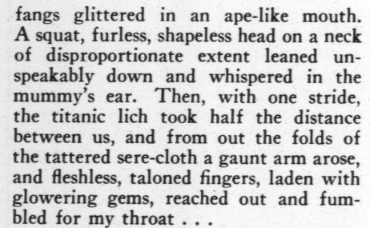

Smith was a Californian through and through, in the same way HPL was a New Englander and REH was a Texan – regional writers whose backgrounds and environments shaped them fundamentally! And Smith lived in a particularly striking landscape, surrounded by the Sierra Mountains and, in particular, the spectacular scenery (and geology) of the Long Valley caldera!

I told you I was going to be indulgent! Now, if you’re not familiar with geologic maps, no worries – what you’re seeing here is the underlying geology of CAS’s ol’ stomping grounds, a vast and complex terrain of extensive volcanics squished up and extruded out onto a region of heavily extended Basin-and-Range mountains. It’s chock full of huge craters, thick ash tuffs, and weird hydrothermal systems, mountainous and broken and wild! Here’s a simplified map:

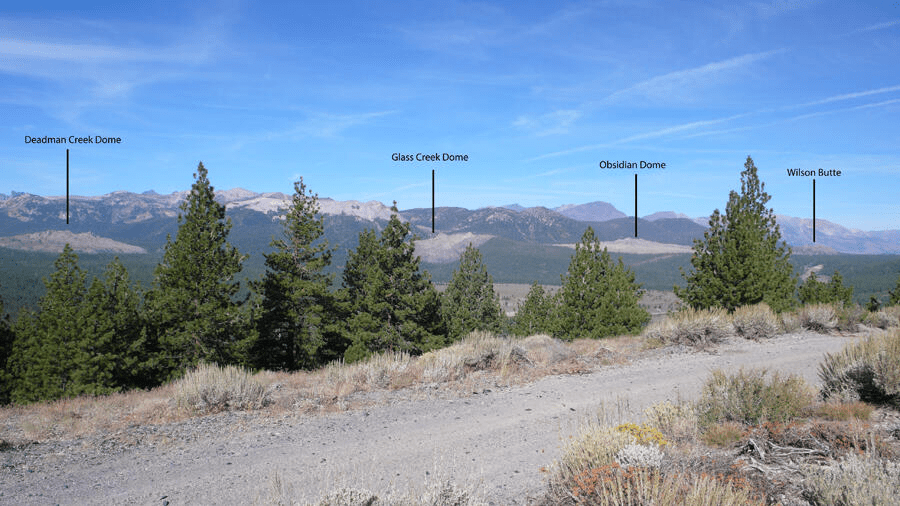

Craters, lava flows, ashfall tuff, faults…it’s a busy landscape! In fact, here’s what it LOOKS like on the ground (all these pics were grabbed from the USGS’s Long Valley Caldera Field Guide):

That’s a hydrothermally fed creek, full of weird plants, strange precipitated minerals, and weird geochemistry…you can just imagine a strange bat-headed nine-legged hellbeast creeping down for a sip on the banks there, can’t you?

Above is a pic of the famous “Devil’s Postpile,” a basaltic lava flow that fractured into the columnar patterns you see while cooling. Real “ancient ruins of a lost civilization” vibe too, dontcha think?

The whole area is volcanically active and pocked with weird craters. These are explosions from within the earth, but you can imaginatively reinterpret them as asteroid craters, if you were a weird fiction writer!

The volcanism is expressed on the surface by a lot of raw, fresh looking rock, the product of active eruptions, that often contrast markedly with the surrounding landscape. Remember the weird monster-backed mountains from the story? Well, I mean, these are them:

There’s even a deadly aspect to this landscape – the active volcanism means there’s a lot of volcanic gases leaking out here and there, with CO2 plumes killing plants and people over the years. It’s a wild, woolly landscape, visually and psychically striking, a clear influence on both this story and the way Smith approaches his weird fiction. Whereas HPL was often focused on decay and decadence in the landscape, the environment reflecting rottenness and perversion, I think Smith’s use of the environment highlights its alienness and inhumanity. There’s surely ancient decay in Yondo, but it’s sort of ancillary, the product of humans trying to live in this place at one time, a place fundamentally and existentially antagonistic to the vanities and illusions of mayfly-like people and their temporary civilizations. For Smith Nature is both Red in Tooth and Claw, but it’s also Purply and Green and Ultraviolet in Tentacles and Too-Many-Jointed Legs and Weird Minerals.

What I think is important about this story is that Smith is showing us a key part of weird fiction – twisting and skewing and finding strangeness in the world around us. Interestingly, Smith is always playing with that idea, too, suggesting that perhaps our idea of weirdness is a result of our limited perspective. For weird nine-legged bat monsters, Yondo might be a perfectly nice place to live – it’s just not so for us humans! That glancing contact with outer realms is what makes weird fiction work, and really anchors Smith’s fiction in a very visceral, very strange world.

And importantly, Sword & Sorcery is a sub-genre of WEIRD FICTION! Which is why this Smith-ian approach to landscape, one that Howard would also pursue, is so important – S&S confront its heroes with weirdness, first and foremost, for them to conquer (or at least survive). The immersion of a characters (and readers) in a weird landscape, one where there is alien agency and alien rules, is such an important, fundamental part of the genre, and Smith is a master of it! His poetical aesthetic is important, but so is his having lived in a truly stunning landscape, one dynamic and alive and strangely active beyond anything a human can really grasp. “The Abominations of Yondo” is weird fiction, but the way it centers not the human, but rather the human experience of the unhuman, is a perfect crystallization of both weird fic AND S&S’s power and scope!

PLUS, goddamn but those are some great monsters!!!!