Running down the clock here in August, and with those crisp mid-90-degree days starting to show up it’s feeling like we’ll be in spooky season soon enough; but before we return to weird horror, I want to dive into some some pulp sci-fi. So, for this, our twenty first edition of Straining the Pulp, let’s take a look at a true foundational classic from one of the genre’s greats: “The World Well Lost” by Theodore Sturgeon from the very first issue of Universe Science Fiction dated June, 1953.

Now, as is custom around here, I want everybody to take a minute, click on that link, and go read the story. It’s not too long and I think you’ll get a lot more out of it if you go into my meandering musings with it rattling around in your skull. It’s an important story in the history of sci-fi, so don’t deny yourself the pleasure of experiencing it as the readers of 1953 would have come across it! Okay?

I said above that Sturgeon was one of the genre’s “greats,” which you might find surprising if you’re not steeped in pulp literature – he was never a huge seller, never had much critical success or even outside recognition, and was published mostly in second-string magazines. But, among sci-fi writers of that and later eras, Sturgeon is one of those artistic darlings whose works were considered some of the most important and influential ever published. He’s similar to Al Bester or, later on, Gene Wolfe – powerful writers whose influence far outstripped their financial success. He was a huge influence of Samuel R. Delany and Harlan Ellison, for example, two writers who pushed the boundaries of science fiction in ways that are instantly recognizable as a part of Sturgeon’s legacy.

He’s also famous as the inspiration for Vonnegut’s character “Kilgore Trout,” a soulful if shabby genius whose writing was always trapped in porn mags or z-tier pulps. Sturgeon got to know Vonnegut when both were living in the same town in Massachusetts; this was before Vonnegut was “Vonnegut” mind you, and it’s quite telling that Sturgeon (and his circumstances) made such a strong impression on ol’ Kurt that he was immortalized as one of the great characters of 20th century literature.

Sturgeon was fairly prolific, although there were some long fallow periods where he suffered from apparently debilitating writer’s block. His most famous work is, probably, “Baby Is Three” from Galaxy in 1952, although you might also know him from “Killdozer!” a story a million times better than its premise has any right to be (something true for the later made-for-TV movie based on it, by the way). He wrote some famous Star Trek episodes, “Shore Leave” and “Amok Time,” the story where the emotionless and logical Mr. Spock gets so horny he loses his goddamn mind and attempts to kill Kirk.

Sex, gender, and their role in the way society is constructed and enforced are common topics in both Sturgeon’s writing and his life. You want to be careful with labels, because they can have political or social valences today that people in the past would never have subscribed to, but Sturgeon was a queer writer – he was married to a woman with whom he had numerous children, but he also liked to have sex with men. This fact is relevant to our story in particular today, since it’s often called the first “modern” gay sci-fi story.

A quick look at the cover of this magazine shows that everyone was well aware of the boundary-pushin’ nature of Sturgeon’s story, which they specifically call out as his “Most Daring Story” to date! Samuel R. Delany has, in a couple of interviews, brought up the fact that Sturgeon’s first attempt to get this story published resulted in the editor of that magazine not only rejecting it, but in calling around to OTHER editors to basically blacklist Sturgeon and keep him from publishing it ANYWHERE. This didn’t stop the editor of Universe Science Fiction, “George Bell” who was actually a name shared by Ray Palmer and Bea Mahaffey. Palmer is a hugely interesting and important figure, far to huge of a subject to get into now, but, sufficed to say, that the iconoclastic and publicity-loving Palmer accepted this story is not too surprising. (Bea Mahaffey is likewise a very interesting and important figure in the history of sci-fi…we’ll ALSO have to come back to her one of these days!)

But enough! Let’s dive in to the story already, yeesh!

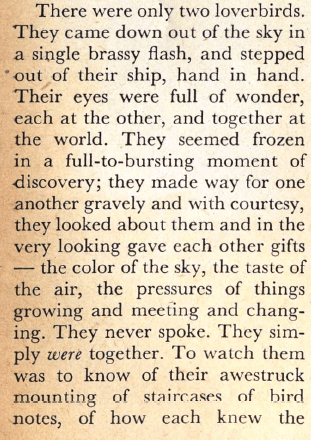

A nice, bucolic scene, rolling hills a distant town’s battlements…nothing too surprising or interesting here on the first page…but…on the adjoining page, we come across something much more striking:

A striking image, and one that’s even more straightforwardly queer than the story, initially! These are the two “loverbirds” of course, but in this image there’s very little ambiguity, whereas the story plays a little coy with it, at least for a while.

The story starts with a discussion of the arrival of the “loverbirds” as something that’s done and overwith – it’s happened already, and their brief stay of nine days is already in the past. There’s some fun, classic Sturgeon world building going on – Earth is a both paradisiacal and shallow, a world dominated by “orgasmic tri-deo shows” and other such fantastic modes of consumption and experience. But still, there’s something wild and special about these two beings, the “loverbirds” who have arrived on Earth.

So, these two enigmatic beings arrive on Earth, dissolve their ship, and become this sensation across the whole world, largely because there’s a kind of magical intensity to them and their obviously profound love for one another. Like I said, in the story, there’s very little to indicate what these beings look like – the bird metaphors up front convey a kind of delicate beauty, but importantly there’s no explicit gendering of either of the aliens. There’s simply a “tall one” and, therefore, a short one. A reader in 1953 might simply assume a standard, heteronormative pair, a boy alien and a girl alien, although they might’ve wondered at the illustration.

Anyway, these intensely lovey-dovey aliens are a huge sensation on Earth, of course, which leads to the authorities becoming interested in them, as well as any uses or dangers they might present. So they feed all the relevant data about the loverbirds into a big ol’ supercomputer, and what do they get? The electronic brain spits out a single word: “Dirbanu.”

Dirbanu, we’re quickly informed, is an intensely enigmatic world, one of the few that Earth had been unable to have any contact with – whenever they try, they’re rebuffed, and the Dirbanuvian defenses are impenetrable and perfect. Earth realizes that these aliens must be mysterious travelers from Dirbanu! And, because of the sheer volume of Loverbird media being beamed out into space, Dirbanu becomes aware that these two have arrived on Earth…and they demand the return of these two fugitives!

Great, fun writing from Sturgeon again; I especially like the realpolitik that he’s explaining in the asides here. It’s also a great and cynical switcheroo – we started with this ideal couple who have captured the world’s imagination, symbols of beauty and wonder, profound in their love…and then these refugees get locked up and shipped out because there’s a political advantage to be had from returning them to the world they fled from. Grim stuff!

The story shifts to the hastily organized prison ship, the Starmire 439, and we’re introduced to its two-man crew: Rootes, a small, cocky little feller who is the Captain of the expedition, and the sole crewman, a hulking, meditative, and shockingly literary man who goes by the name of Grunty. A real odd couple, it turns out that these two only ever ship out with one another – indeed, neither could actually function with anyone else:

So, despite being extremely weird guys, these two work so well together that they’re basically the best spacemen in the business – no other crew can handle the difficulties of long distance space travel like Rootes and Grunty, who even seem to, in some strange way, thrive in each other’s company. So in synch are these two, in fact, that they always and predictably react the same way to the FTL super-science engine of the ship: Rootes konks out for 2 hours under the influence of superluminal travel, while Grunty is up after a scant thirty minutes.

I imagine most people would already at least have gotten an inkling of what’s going on here – the idea that these two are so smoothly in simpatico is one thing, but that of the two only bookish contemplative Grunty knows what the bond is between them (and that it CANNOT under ANY CIRCUMSTANCE be communicated to Rootes) kind of heavily underlines it. Still, it’s 2024 and maybe we’re all used to these sorts of things in a way that the readers of 1953 weren’t!

Anyway, Sturgeon gives us some great scenes aboard the ship, with Rootes wearyingly recounting his latest sexual conquest back in port to a resigned Grunty. Its fun, and we get further glimpses of Grunty’s interior life when he goes over to check on the two prisoners:

Yup, turns out these here aliens are PSYCHIC…and that’s a real problem for Grunty…

Very little room left for doubt about what Grunty’s secret is, but it’s still being left unsaid, a elision left for the reader to fill in. Regardless, we’re given a sense of Grunty’s animal panic at having his quiet, secure, secret inner self suddenly exposed. Grunty soon comes to hate the loverbirds, even neglecting to feed them until Rootes, recognizing something is wrong, harangues him into doing the bare minimum of upkeep for the prisoners. Grunty’s fear apparently is that the loverbirds, possessing his secret, would inevitably communicate it to others when they get to Dirbanu, and from there it would, doubtless, spread back to Earth. This is kind of a wild, crazy idea though, and it seems that Grunty’s secret is so profound, and its exposure so terrible, that he’s kind of lost his mind a bit here. There’s a great section, after Grunty gives Rootes an art book to ogle, where he’s mulling over the fact that there are still certain things considered taboo and forbidden, even on so free-wheeling a world as Earth, and how it took half-a-lifetime for Grunty to discover a way of life that afforded him some freedom (even if it is only for the brief moments of solitude afforded him by the superluminal blackouts). He cannot afford to even consider what the loss of this fragile freedom would mean for him, and so he comes to the conclusion that there’s only one way out for him: Grunty has to kill the Loverbirds.

The “How” of his murder puzzles him for a bit – he’s got to kill these aliens, but how to do it in a way that wouldn’t cause trouble for him and, particularly, Rootes. He can’t just smash their heads in, and there’s no way to poison them…but then Grunty, with his keen insight into human psychology, realizes that a sawed-off little popinjay like Rootes would have to have a gun somewhere. Sure enough, he’s got some kind of murderous death ray stashed in his stuff. And so Grunty gets it and, while Rootes is still under FTL coma, prepares to protect his secret by blasting the aliens.

But, just as he’s about to pull the trigger, the aliens show him some pictures that they’ve drawn. The first picture shows, with startling clarity and precision, Grunty and Rootes and a girl. The second picture is of the same three, but naked (Grunty wonders how they learned about human anatomy). Then a third picture shows the two loverbirds flanking a strange, round, little critter. And the fourth picture?

The scene closes, and we start up with Rootes, waking from his superluminal torpor to find Grunty standing solemnly over him. He soon learns that the loverbirds are gone, having taken the ship’s life boat and vanished into space. When he asks how it happened, Grunty admits to him that he let them go. At first Rootes is enraged, furious that he’s gotten them in such trouble. But, slowly, he learns that A) the two escapees have no intention of traveling to Dirbanu and B) Grunty is planning on simply lying to the Dirbanuvians that the two loverbirds died – it seems that they isolationists of Dirbanu don’t have any ships to check on the claim anyway. But why, asks Rootes? In answer, Grunty shows him the pictures the loverbirds drew.

Rootes comes to the conclusion that Grunty helped the loverbirds escape because he didn’t want Rootes to get in trouble for killing a pair of gay aliens, like any red-blooded human man certainly would, especially one so profoundly and deeply and sincerely heterosexual as Rootes. Yessir, he was just looking out for his buddy, good ol’ Grunty.

Rootes homophobia, presumably a typical expression of the status quo back on Earth (and a part of what Grunty had been fleeing from) is one-up’d by the Dirbanuvians who, when contacted, seem appreciative of the fact that the the humans did ’em a solid by killing the deviants. Of course, politically, nothing has changed – like Rootes said, the deep loathing for homosexuality that underpins Dirbanu culture is so strong that they can’t stand to even think about Earth, with its too-similar genders making them all uncomfortable as suchlike. Nothing to do but head home!

And that’s the end of “The World Well Lost” by Theodore Sturgeon.

I mean, it’s a hell of an ending for a hell of a story, isn’t it? Meditative, sad, but still a bit hopeful. The virulence of homophobia is really well portrayed – in Rootes’s outsized performative heterosexuality and in his insistent regurgitation of standard homophobic slurs and ideas, he comes across as a tragically repressed closet case, someone who thinks that if he’s to survive in the world, he has to bury himself completely in order to conform. And Grunty, facing a similar set of circumstances, has found a way of life barely any better – escaping the hateful Earth by living in space, unable to express himself to the man he loves except for in those brief moments of space-travel-induced blackouts. It’s tragic stuff, but I think its saved from rank maudlin-ness by the fact that Sturgeon is such a deft and controlled writer who, even when dealing with complex and difficult subjects, is still able to construct a plot and characters and story that moves you along irresistibly.

I think it’s a testament to the pulps that a story like this was (eventually) published in 1953. It’s very easy to dismiss these magazines as cheap and disposable entertainment (nevermind the fact that 35 cents in ’53 wasn’t exactly nothin’) but there’s more to them than trashy ray-gun stories. Because of their marginality, marginal writers could (and sometimes did) find homes for stories in them that otherwise might never have seen the light of day. And while it is true that there’s a lot of reactionary bullshit in them (and overt racism, sexism, etc) there’re also stories by authors whose identities would not have fit comfortably in the world at large back then (or now, sadly).

Also, frankly, there’re some real good writing in them too. Sturgeon is a great writer, and there’re some stirring and striking passages in this story, aren’t there? Real lyricism comes through here, I mean at the sentence level, without even considering the topic or themes. There’re some recent collections of Sturgeon’s work, multivolume affairs that publish his stories and novels, that’re worth hunting up. I think his position in the history of SF is important, too – like I said earlier, he’s the foundation of what would, eventually, become the vibrant New Wave sci-fi of the 60s and 70s, in large part because he tackled complex subjects with real style and insight.

Now, I wouldn’t blame you if you felt that there’s a whiff of the “tragic queer” about this story – it’s certainly true that this story is underpinned by the melancholy of oppression. But, to that point, this was written in the fuckin’ 50s man…and as bad as homophobia is now, I think it’s worth appreciating the position back then. Just tackling the topic in the first place, let alone with the tenderness and care that Sturgeon is taking here, is remarkable.

Finally, themes and such aside, I’ll just come back around and say that Sturgeon is a great writer, one of the best of his generation in the genre, certainly. He’s worth your time, is all I’ll say!

Pingback: Improvised Contraband Prison Pulp Strainer #23: “Cellmate” by Theodore Sturgeon, Weird Tales v. 39, n.9, January 1947 | Eric Williams