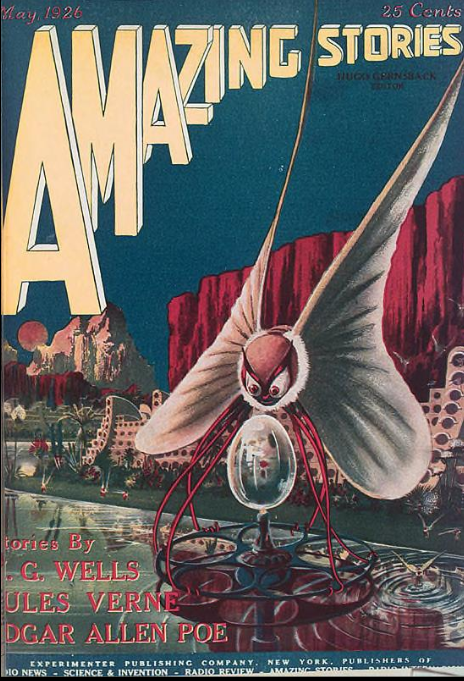

Lookit us, breaking out of “Weird Tales” and into some honest-to-gosh science fiction (or, as Hugo Gernsback preferred, “scientifiction”)!

This is the first issue of the very first magazine devoted to science fiction ever, making 1926 basically the date at which you can pin the creation of the genre. I know people like to wax moronic about Lucian of Samosata and Mary Shelley and all that older stuff, and certainly it’s important, but the fact of the matter is that, until Hugo Gernsback started publishing magazines, no one would have said that what they were reading (or writing) was “science fiction.” It was in this magazine right here that the genre was defined and delimited and created, by readers, writers, editors, and publishers, who had a dedicated space to wrangle and argue and pontificate about what was (and wasn’t) science fiction!

That being said, there’s also an interesting aspect to the creation of the genre that’s immediately noticeable right there on the cover of the magazine. Take a look at those authors: Wells, Verne, and Poe. If you look inside at the ToC, you see that there’re other names there too, though interestingly NONE of the fiction in this first issue was written for the magazine; they’re all reprints, either of “classics” or of stories that were previously published in Gernsback’s older radio and electronics news magazines.

It would actually take a while for the stories to start being “originals” for the magazine – the whole first year of Amazing Stories is absolutely dominated by Verne and Wells, often with their longer works stretching over multiple issues. This is, interestingly, different from Weird Tales, which actively made a call for submissions in writers’ magazines and professional journals before it’s first issue was published. I haven’t run across any advertisements like that for Amazing Stories, and it certainly seems like Gernsback had a very definite plan in mind to use these older and “classic” works in his magazine.

ALSO interesting, to me, is that Poe is such a major figure in here. This is 1926, Weird Tales has been chugging along for 3 years already at this point, but the tangle of “science fiction” and “weird fiction” is still very evident in both of the magazines. Interestingly the George Allen England story there (“The Thing From – Outside”) is also 100% a weird fiction “monster from beyond” horror story. These broadly speculative and imaginative literatures are so intimately intertwined at this time, and only with the nichification of the pulps did they develop the kind of rigid boundaries that we tend to think about today.

Anyway, the story that we’re going to talk about today is Wertenbaker’s “The Man From the Atom,” which is a two-parter that stretches over these first two issues. The first part, written as a standalone, was originally published in an earlier issue of Gernsback’s Popular Science-like magazine “Science and Invention.” The sequel to the story is actually the first original fiction published in Amazing Stories. Wertenbaker is an interesting guy; he’d write a bit more sci-fi early in his career, then turn to historical and regional novels, then became an editor at some major magazines. After WWII he’d end up at NASA as a speech writer, and would eventually become a big part of their space medicine program as a documentarian and historian. Interesting dude!

A thing to note about “The Man From the Atom” part the first is that Wertenbaker wrote it when he was fifteen, and it shows! It’s really overwritten, even for the time, with extremely purple prose and some brutally tortured sentences. The science in it is goofy as hell, of course, but it illustrates just how big of a deal Einstein was at the time, and how influential relativity was on popular culture.

First thing first, though, are these little intro boxes that Gernsback (or one of his flunkies, although I’m inclined to think they’re from ol’ Hugo) wrote at the beginning of each of these stories. Here’s the one for “The Man From the Atom:”

A big part of Amazing Stories, especially early on, was the lengths to which Gernsback went to argue that scientifiction was an “improving” literature – it was both artistically sophisticated as well as educational. In fact, later editorials by Hugo would go on to claim that many scientists were writing him to let him know that they chose their careers BECAUSE of his magazine. This text is interesting, because he’s really playing up the literary merits of the story rather than it’s science-y aspects, probably because even for Amazing Stories the science in “The Man From the Atom” is pretty fantastical.

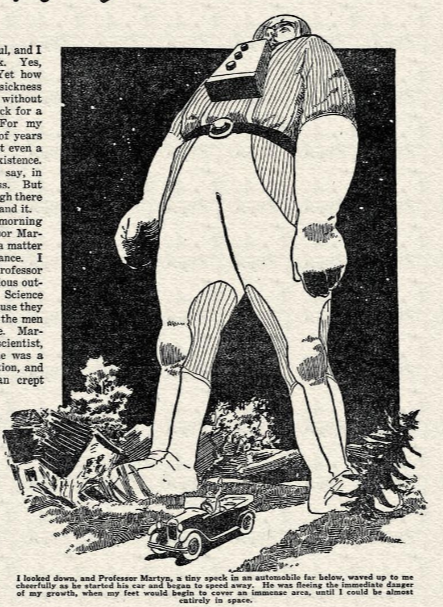

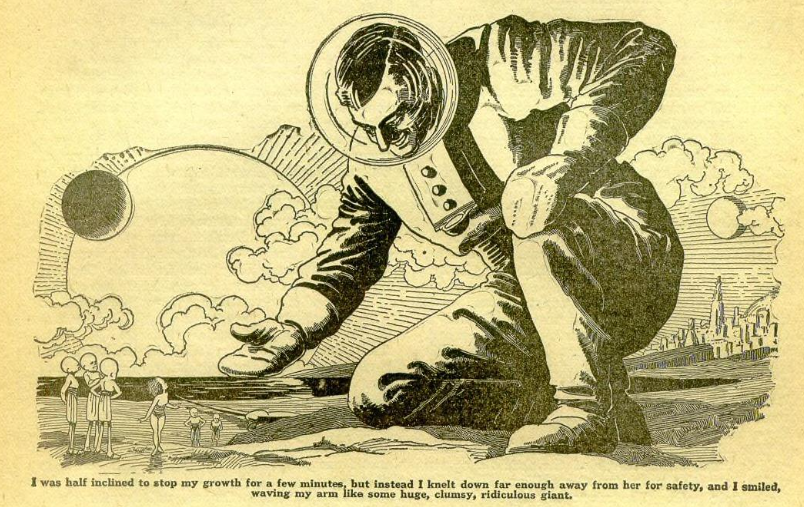

But before we get into it, check out this incredible title page art for the story! Amazing Stories had such great interior art, right from the beginning, it’s really a treat.

Between that art and the little blurb box, you know what’s coming: this is a story about a Boy what gets Big.

It starts with the narrator lamenting his fate, real sad-sack style. But then he buckles down and shares with us His Strange Tale. Seems our boy, called Kirby later in the story, is basically a Guinea Pig for a wild-eyed weirdo inventor names Professor Martyn. Their relationship is summed up on the first page fairly succinctly, if oddly:

This maniac Professor Martyn basically invents weird stuff and Kirby eagerly tries ’em out, which is hilarious. Imagine being so “romantic” that you’re like, “yeah man, blast me with that ray!” or “sure, I’ll drink this bubbling vial of strange fluid, no problem.” But Kirby doesn’t give a shit; he’s down for anything. And that includes the Prof’s most recent invention, a machine that he accidently invented and doesn’t fully understand, but that basically can shrink or grow a person infinitely. And Kirby is pumped as hell to try it out:

It’s really funny to imagine embiggening as the secret to unlocking all astronomical mysteries. Glad to know a giant foot isn’t going to smash the Earth though, good that the Prof has already determined that. They soon get down to brass tacks:

Suited up, Kirby prepares to expand himself to cosmic scale. It’s kind of fun to consider the writing of this story from the perspective of a nerdy teen sometime before 1923. Rocketry as a viable discipline was still well down the pike, and the question of exactly how people are going to explore the universe and learn about space was still, really, a wild and fully speculative exercise. So the idea that this character is going to learn about planets and stars and stuff by just getting fuckin’ huge is, while extremely silly, also extremely imaginative and unprecedented.

Kirby and the Prof drive out to a secluded spot and begin their test. There’s some fun writing in this part, a real attempt by the author to describe the sensation and observations of someone growing exponentially to cosmic proportions.

It’s all fun and games though until Kirby grows to such a large size that he begins to experience the rotation of the earth under his feet, like he’s balancing on a ball. It’s very disorienting, and eventually he simply slips off the tiny earth, and floats powerless in space, watching the planets and the sun whizz by in every faster arcs. And as he keeps right on growing, the planets vanish and other stars come to dominate his vision; he grows beyond our solar system.

Fun cameo from “the ether” here, the old and, even in the 1920s, discredited idea of the interstellar medium that allowed for the transition of energy. It’s an idea that persists a long time in the pulps, even though it was largely debunked in the late 19th C. and was killed by Einstein’s own work. There’s a whole dissertation to be written on the incomplete and sometimes inchoate way that physics and science in general were incorporated into the pulps!

Anyway, Kirby expands beyond the galaxy eventually, watching the nebula recede until it itself is proven to be but a speck of light in an even larger nebula, and on and on, an ever expanding recursion of eternity, infinitely scalable. Kirby even experiences a moment of transcendent illumination, linking this the largest of scales with the tiniest expression of reality at the atomic level:

Like, woah, man, you know?

But this is too much for Kirby! He gets spooked, and starts to shrink back down. But he’s faced with a conundrum…how is he supposed to find the Earth again? He’s literally as big as the universe, and everything has been in motion around him, and now he’s supposed to find a specific speck in the vastness of space? The first planet he lands on, a warm weird water world, is clearly not the Earth. So, after a recuperative freakout, he decides to try again, expanding and then shrinking, aware of the difficulty but willing to give it a try. And at first it seems like it’s working, he finds the nebula, the right stars, and expects to find the sun soon…but…it’s gone! Then the final horrible revelation:

That’s right! By gettin’ big, Kirby experienced time at a fundamentally bigger scale – his brief sojourn among the stars, mere moments to him, was millions of years back home. He ends up shrinking down and finding a planet full of big-brained aliens, all of them hugely intellectually superior and scientifically way more advanced than he is; he’s a “savage” among them, a dumb curiosity who can’t learn their language (though they easily learn his). “The Man From the Atom” ends with Kirby trapped forever, unable to ever return to a long dead Earth…

…or IS HE!?!?

The sequel to “The Man From the Atom” is, like I said, the first piece of original fiction published in Amazing Stories. Here’s the cover from that issue, with a rad alien on it:

Our story picks up with Kirby saying that, yeah, he might’ve come off a little dramatic and despondent in his previous story, but it wasn’t ALL bad. For one thing, he met this big-brained cutie named Vinda!

Vidna digs him, and makes his time on the alien world almost pleasant. Of course, he still yearns for the Green Hills of Earth and all that, so one day, Vinda comes to see him with a plan.

That’s right: the curvature of space-time = yuga cycles, basically, and if Kriby just gets himself big again and lets the universe spin for a few zillion years, he’ll come back around to, basically, the same Earth that he left, reborn in one of the infinite cycles of existence. It’s a fully bonkers idea, but it resonates kind of nicely with the spatial scaling stuff in the previous story, where the universe is like an atom in a bigger universe etc etc. Fully stoner sci-fi, but it’s absolutely non-derivative and novel in 1926.

Of course, nothing is ever easy, is it? It turns out that there’s some sort of weirdly “progressive” direction to history, so that even with its cyclic nature Kirby will return to a slightly changed, slightly more advanced world than when he left. It’s never really explained why this is, in the story; rather, it’s just an obvious, natural function of time cycles. Kind of a weirdly comforting idea, and one that you can absolutely see as coming out of the particular moment of the post-World War I american boomtime, what with the wonders of the modern age – it’s a particularly golden age sort of science fiction concept, that of course everything will always be somewhat better, at least iteratively.

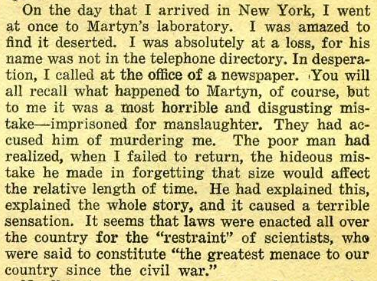

Anyway, Vinda helps Kirby write up a star chart from when he left Earth, which will help him ID the time and location of Earth. He does his cosmic expansion thing and, with his careful preparations, actually does cycle back and finds the Earth at roughly the time when he left it. He shrinks down and finds himself in the Sahara, back home in good old’ late 1840s, although its actually as advanced as the 1940s of Kirby’s original timeline/cycle/whatever! He finds himself back in New York and discovers that Professor Martyn is in jail for his murder! It seems that in this cycle they did the experiment also, and everybody blamed Martyn for Kirby’s dissaparence. In fact:

Kirby’s reappearance causes quite a stir, and Martyn is released from jail and presumably scientist are taken off the terrorism watch list. There’s then a chunk of the story that explores some of the alternative history of this cycle of the Earth:

That bit about Teddy Roosevelt and the Great War of 1812 is weird – in our “cycle” of course Roosevelt wasn’t born until 1858, and the “Great War” of 1812 seems to imply that WWI happened nearly a hundred years earlier. I guess that this is some of that “accelerating advancement” stuff that is inherent to these cycles, but I wonder why the author chose those particulars. Guess we’ll just have to wait for the book by Kirby and Martyn. Anyway, who cares, because tomorrow Kirby is going to travel the cycles again in search of Vinda, whom he now realizes he’s passionately in love with. Of course, the inescapable logic of this cyclic universe crap leads to some odd musings:

So that’s it, the very first piece of original sci fi written for Amazing Stories. It’s an odd one, and I don’t know why the author wanted to write a follow up – honestly, to me, the ending of the first part feels perfectly satisfactory. I think the interesting thing is how, in these early days of pulp sci-fi, the fantastical elements of modern physics and invention has an absolute stranglehold on the imagination. These kind of way-out ideas, like a device that makes you grow so huge that you experience time in a fundamentally different way, are a lot of fun and also speak to a very different mode of science fiction. In a couple years, E.E. “Doc” Smith will start publishing his Skylark stories in Amazing, and that’ll be a huge change – those stories, and Smith in general, kind of invent the Space Opera subgenre, and two-fisted thrilling action sci-fi comes to quickly dominate the early pulps. Similarly, socialist science fiction writers in the 30s, as well as the general collapse of the economy in the Great Depression, will lead to a newer, grimmer, more psychologically and socially oriented flavor of sci-fi. But in these early years of the genre, and particularly as envisioned by Gernsback, there’s a real, honest-to-goodness “gee whiz” style to these stories, not necessarily in a kiddie way; rather, there’s real excitement about invention and imagination in them, and an emphasis on humans interacting with weirdness on the bleeding edge of science. They’re fun, is the thing, and they’re also so very original, that they’re honestly just a pleasure to read.