I promise these won’t all be about stories from Weird Tales! I’ve got some stuff from Amazing Stories, Black Mask, and Astounding that I want to hit eventually, but Weird Tales is such a huge, important magazine, and its story is so interesting, that we’re definitely going to be seeing a lot of it. And this week is no exception, with Anthony Rud’s (kind of unpleasant) story of grisly murder, art, and madness, “A Square of Canvas.”

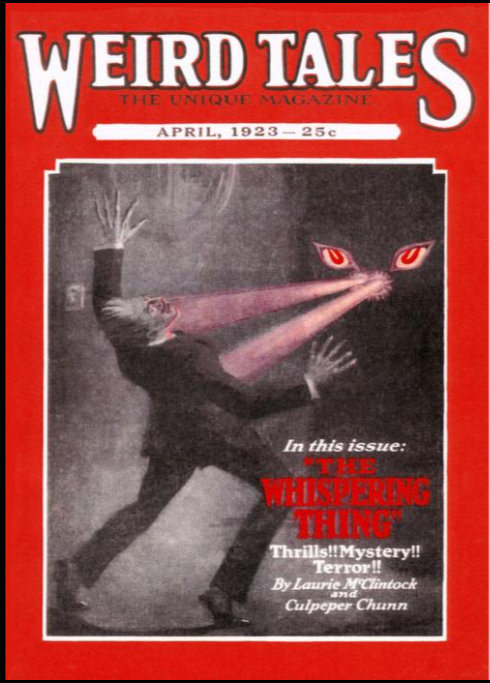

This is the second issue of Weird Tales, from May, 1923, with a cover by (I think) R.M. Mally. You can definitely tell that Baird is still trying to find his footing with the stories and general thrust of the magazine. Take a look at this little descriptor above the ToC:

It’s interesting for a couple of reasons, one being that there’s a lot of “two-part” stories, meaning that they’re being spread across multiple issues. This is something that you see a fair amount in Weird Tales, especially early on, and man, did the readers hate it. Lots of miffed letters complaining about how annoying it is to wait for a month to find out the next part of the story, with all the attendant dangers of forgetting what happened or missing an issue. It’s obviously an attempt at hooking an audience, since it’s used a LOT in the Baird era (1923-1924), even though the magazine is incredibly long at that point and could easily have accommodated these longer pieces; this issue, #2, is nearly 200 pages! You’ll see some things split up later on, but after Baird leaves and Wright takes over, there’s an effort to avoid it, much to the appreciation of the readers.

The second interesting thing in that little description is the “interesting, odd, and weird happenings” bit, which refers to things like this:

These goofy little articles appear as page filler below the endings of stories throughout these early issues, unattributed and unsubstantiated and generally of a broadly defined “weird” flavor. The one above seems tenuously related at best (a brief allusion to “spook” plays seeming to be the only weird thing to recommend it), but it DOES have a common thread with a lot of the other “strange interludes” scattered throughout the magazine: a scientific bent. Here’s another:

(As a side note, this one is 100% false – the earliest human remains in South America date to, at the oldest, 40,000 years, though most workers accept 26,000 years before present as much more likely).

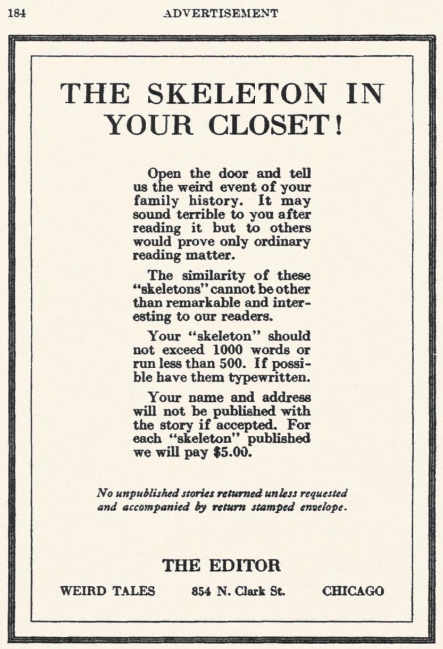

A lot of these, as mentioned above, are science-y at least, although there’re also a fair number of “horrible murders” included. But you can really see by their inclusion that the idea of “weird fiction” is still being hashed out; there’s a lot of strange, abortive attempts at including things like this in the magazine, seeing what sticks and what doesn’t, conceptually, as weird. Baird, a fan of crime fiction and a veteran of the detective pulps, clearly thought stuff like this was important, since he actively solicits “weird shit that happened to you!” in the back of this issue:

These sorts of things eventually go away, replaced by art or better page layouts that eliminate white space, but ALSO because the second editor, Farnsworth Wright, hated this shit. Time and time again, he studiously ignores the calls from readers in The Eerie to include “real life” ghost stories, Fortean-type reports of weird stuff, and even “strange dreams” that readers wanted to submit. Wright (thankfully) had a clearer, exclusively literary idea of what the weird genre could be, and took a lot of strong editorial decisions to put it into practice.

But that’s all in the future! Here, in May of 1923, with Baird at the helm, we’ve got the second issue of Weird Tales, and it’s really not good! The only recognizable names on the ToC are Farnsworth Wright, Otis Kline (who will be hired alongside Wright by Baird after this issue as a reader and editorial assistant) and Anthony Rud. Reading through the issue, what really stands out is how much crime/murder stories still dominate Weird Tales – there’s some occultism and some supernaturalism, a monster here or there, and some weird science, but a solid half of these stories are just “watch this psycho brutalize someone.” Which brings us to our story today, Rud’s “A Square of Canvas.”

Now, first thing first – this is not a good story per se. There’s some neat bits, and it’s interesting (though ultimately inconsequential) that the narrator is a woman. But there’s also some real unpleasantness here in the form of cruelty to animals, so be warned! What makes it worthy of contemplation, at least in my mind, is that it’s a very early version of the “Freaky Artist” trope, which has a long history in both horror and weird fiction. Perhaps its most famous expression will come in 1927, when H.P. Lovecraft publishes “Pickman’s Model” in Weird Tales, but Rud’s take on it here is a striking early example.

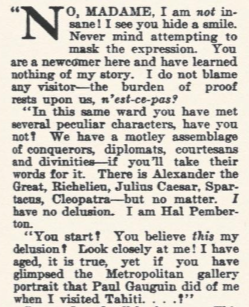

It starts, as these things often do, in a sanitarium:

This is a fun bit of dialog, very vital and effective; you can feel the urging and the eagerness of the speaker who, clearly, is coming off a little intense. It also employs one of weird fiction’s most versatile and fun little tricks, the mixing of fact with fiction. This weirdo is trying to convince a woman that, while he recognizes that he’s in an insane asylum full of people who think they’re famous figures from history, HE at least is who he says he is, and he does this by referencing a portrait of himself done by Gauguin and hanging in the Met! A fun little example of something very much specific to the weird genre, this blending of reality with strangeness.

The woman Hal Pemberton is speaking to is, it turns out, also an artist, and so she is certainly familiar with the Gauguin portrait he’s speaking of. With a gasp she realizes that she DOES recognize this guy – he’s older, with greyer hair and more wrinkles, but he DOES in fact resemble the picture! Gratified by this, Pemberton confides in her that he has been imprisoned in this institution by mistake, and hopes that, by unfolding his tale, this unnamed woman will help to get him released, for he is an Artist, and has much Great Work to do!

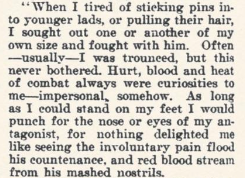

This begins the the meat of the story; Pemberton, the scion of an affluent family, has a hard time in school as a child. He finds his lessons boring, and in fact the only thing he takes pleasure in is tormenting his classmates. He likes to pinch them, kick them, pull their hair, eventually graduating to full on brawls. He loses as many of them as he wins, but for Pemberton, that’s beside the point. What he likes is pain:

This is pretty good writing – you get a reeeeeeeal uncomfortable feeling reading this, a pretty effective sense of a deeply and fundamentally fucked-up kid. You also probably see where this is going by this point; unfortunately, the story is going to take its time to get there, with some unpleasant detours along the way.

Pemberton ends up getting kicked out of school and goes through a succession of tutors, all of whom are implied to have quiet as a result of Pemberton’s weirdness or stubborn refusal to learn. His last tutor makes the mistake of leaving him alone with some live beetles that they’re studying, and Pemberton does the thing that you knew was coming. He tortures the beetles, and while he’s doing it he sketches something, specifically using their agony and suffering to fuel whatever it is he’s drawing. His tutor returns and sees what he’s done, but also sees the drawing he’s made. Hilariously, his horror at his pupil’s cruelty leads him to quit, but not before telling Pemberton’s dad that he’s a good artist and should be sent to art school. Can you imagine that scene? “Hal’s a fuckin’ sadistic little creep, but damn can he draw!”

Pemberton is exiled to Paris to study art, where he’s perfectly competent but not as “inspired” as he was with the beetles. Again, you know what’s going to happen, but it doesn’t make it any less unpleasant of a read. There’s some very unpleasant stuff with some rabbits and a horse, and a through-line of the need for escalating violence to spur the artistic inspiration sought after by Pemberton. It’s all quite ugly. I do think it’s interesting how Rud clearly makes his freaky artist a sadist for ARTIST REASONS ONLY; there’s not a hint of sadistic sexuality in this story, not even an upcoming section where you’d expect it. I wonder if there was any in the original and it got cut or edited out? From the editorial statements of Baird, there’s a clear worry, even this early on, that people might think Weird Tales was a little too degenerate for public consumption, so it could’ve been removed. But it also might reflect Rud’s actual intention – he wants to focus on weirdness, and, honestly, a freak who does the sort of shit that’s in this story not for fetishistic but, rather, purely aesthetic reasons is way weirder than some run-of-the-mill sadosexual guy.

Pemberton’s new art is a big hit, initially, but when his teacher in Paris learns about how he went about getting inspired for its creation, he’s horrified. The story gets out and Pemberton is ruined in Europe; so he flees to America where, the facts unknown, his animal-torture inspired work is a huge hit! Oddly, this leads to Pemberton becoming a famous and rich portraitist of the moneyed elite – is that a bit of subtle satire from Rud? Pemberton, whose work is inspired by brutal violence inflicted on the innocent, somehow just resonates with these high society types and becomes their go-to guy for getting a portrait done. Is he, with his horrible insight, capturing something of the truth about these people?

Whether satirical or just silly, Pemberton meets his wife, Beatrice, through this work, and they fall in love, get married, and have a daughter. Now, at this point, interestingly, Pemberton has basically renounced his older work and has chosen to stick to mundane portraits. The trouble is, he’s bored to death by it all, but he’s scared to try and recreate his “experiments” because he knows they might not be enough for him anymore. Trying to stave off despair at his artistic blockage, he abandons portraiture for landscapes, choosing as his subject “dirty, sordid, or powerful” scenes. These include fish markets, ghetto streets, and industrial seascapes; the implication here is that he’s seeking out grim and gritty realism, trying to find the spark of abjectness that always gave his art the fire he was after, but he can’t quite get it.

Finally, driven to a frenzy by his need to produce “real” work, he escapes to the countryside, buys a horse, and does his awful thing, producing a canvas that he calls “Cannibalism.” Now, this is the only real description in the story of the product of his particular method, and it suggests that the cruelty and torture are a sort of spiritual or emotional inspiration for him, since the painting he produces doesn’t have anything to do with horses (rather, it’s a casually racist depiction of “savages gorging themselves on human flesh”). It’s not fully satisfying to Pemberton though, and it almost gets him in trouble when it’s exhibited; his wife ends up making him burn it. But the artistic failure just makes his need all that much greater.

You know where this is all going.

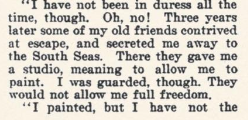

In an inversion of Dante, Pemberton tortures his Beatrice to death, finally creating a painting he’s happy with. The servants, horrified, call the police and Pemberton, afraid that they’ll destroy his masterpiece, hides it. He’s taken in, tried, convicted, but found insane and sent to the asylum. Interestingly, there’s a little interlude in his imprisonment:

That’s a weird part, right? It’s very enigmatical – it COULD be that Pemberton’s society pals like him and want to help him out and send him to Tahiti (where he meets and gets painted by Gauguin), but there’s the odd bit about them basically keeping him under lock and key and forcing him to paint. Are they providing him with “inspiration” too? This part, very creepily, sort of implies that there’s this snuff-painting ring being run with Pemberton at its heart, not that he’s interested; all he can think about is his masterpiece hidden away in his old house. Anyway, let’s wrap this up:

That’s it, The End of “A Square of Canvas” by Anthony Rud.

First thing first: gotta love an italicized ending, right? Just a real classic move, and they’re always delightful when you encounter them. This one is a little strange, and leaves you (or me, at least) with a few questions. Obviously Pemberton is off his onion, but in what way, specifically? Did the torture and murder of his wife break his last tenuous grasp on reality, or is his whole story a fabrication, start to finish? Maybe you’re just supposed to be shocked that, after all this build-up, there’s not even a painting to “justify” it all? Or has Pemberton realized his true art is in the monstrous acts, and no representation of them can ever come close? Maybe Rud just got tired of writing, figured he’d locked in his quarter-of-a-cent per word, and moved on to something else? Dunno! S’weird though, which I reckon is what counts.

The whole story is interesting, although like I said, the animal torture stuff is extremely distasteful – it’s not overly graphic, but for me it’s plenty, and I can’t fault anyone for not wanting to read it. Like I said way up above somewhere, though, I do think it’s really interesting as an early (and possibly influential) example of the Mad Artist trope, something that’s nearly as well represented in weird fiction as the Mad Scientist. Both of them posit an answer to C.P. Snow’s “Two Cultures” dilemma, which is that both disciplines, striving towards some kind of transcendent truth, can lead to madness, ultimately. It’s a deep part of horror and weird fiction; I’d lay good money that it started with E.T.A. Hoffmann’s murderous jeweler in “Mademoiselle de Scudéry,” but it’s all over the pulps.

Lovecraft has a number of mad artists in his stories, the most notable being the painter Richard Upton Pickman from “Pickman’s Model.” In that story, the SHOCKING TWIST is that Pickman, a painter of horrendous and terrible phantasmagoric scenes, is actually a strict REALIST, and he’s been painting not nightmare visions but, rather, accurate representations of real life scenes!!!!!! That’s a story worth reading, by the way, and one I kind of suspect has some kind of relationship to this story – we know Lovecraft was a Weird Tales reader from the get-go, so he certainly read this story, although I don’t know if he ever mentioned it in his voluminous letters. But there’re some things that seem to connect the two – the chatty narration from a character, the emphasis on horror revealed in art, even the description of Pemberton’s “Cannibalism” seems to resonate with Pickman’s “Ghouls Feeding” painting mentioned in Lovecraft’s story.

We tend (rightly) to talk about how the modern scientific age influenced weird fiction (and sci fi, of course) – Deep Time and evolution displaced Paley’s Watchmaker and humanity’s centrality in Nature, an absolute necessity in weird fiction’s decentering of humans in favor of stranger and older forces and agencies. Similarly, early atomic science discovered the reality of invisible and heretofore unmeasurable rays and energies; in a world of X-rays and radiation, who knows what alien processes may be impinging on our placid, narrow little lives? But of equal importance to these revolutions in the sciences are the contemporaneous upheavals occurring in the arts and humanities in the early 20th century. Modernism and Futurism are as big a part of the weird fiction story as Darwinism and astronomy, and the idea of art as a dangerous door to the unknown and madness is one of the major themes of outré literature. Actually, it’s interesting that Rud writes a science horror story for the first issue of Weird Tales, and then produces this mad artist tale for the second issue! Just goes to show how intricately interwoven these ideas are in the history of weird fiction!