Alright! I wanna talk about classic weird fiction and pulp sci-fi and shit like that, so I’m gonna do it here! Very cleverly I’ve titled the series “Straining Pulp,” because it’s me sifting and winnowing old pulp magazines (thanks archive dot org!) and talking about stories I find interesting or noteworthy or fun. I’ll probably bop around a bunch of ’em as my mood takes me, but I figured I’d start with a magazine that is very important to me personally, pulps generally, and pop culture broadly. That’s right, it’s WEIRD TALES #1, from March 1923!!!!!

(Just a heads-up, I’m 100% going to spoiling these stories, so chase ’em down and read ’em aforehand if you want!)

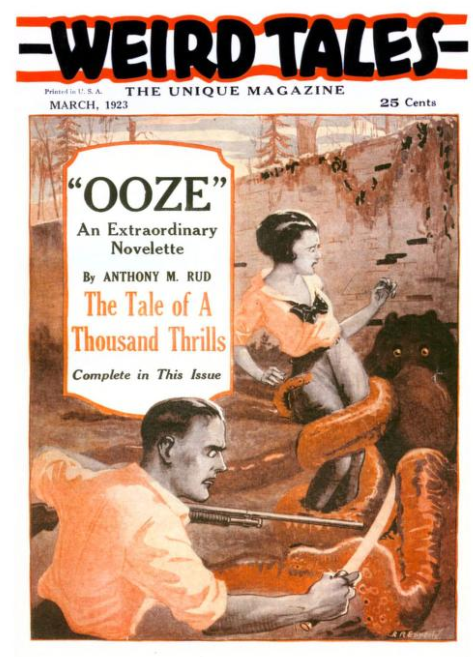

First thing to note is the price on the cover there! 25 cents! There’s a misconception generally that pulp magazines were dirt cheap, but 25 cents in 1923 is something like 5 or 6 dollars today. Not gonna break the bank buying this copy of The Unique Magazine, but still… $6 for a magazine is respectable, you know? These weren’t penny-an-issue cheapos for the kiddie crowd to spend their milk money on, is what I’m saying.

Anyway, this is the very first issue of Weird Tales. Its editor at the time was Edwin Baird, a figure of some importance in the history of the detective/crime pulps, but at this point he’s got himself a job working for Rural Publications, editing both “Weird Tales” and “Real Detective Tales” at the same time. There’s a lot of animus towards Baird today; people tend to think that he hated horror and ghost stories, but I don’t think there’s any real evidence for that. He certainly had a PREFERENCE for crime fiction, but who among us doesn’t have their likes and dislikes, right? It’s important to recognize that, Joshi be damned, there’s no such thing as “weird fiction” until the invention of WEIRD TALES magazine – up to this point there was just a disparate morass of “goose-flesh” stories. It’s a topic for another time, but it’s clear that Baird is fighting his entire tenure against the fact that there’re some serious growing pains going on among the readership (and writers) as they try and decide on WHAT a “weird tale” is, exactly. Most of Baird’s comments in the Eerie (the reader letters section of the mag) start off with him telling people what NOT to send to the magazine. He’s seeing some seriously shitty writing in his time, and it’s definitely effecting his mood!

Case in point: this first issue is, honestly, a mess. The cover story, “Ooze,” gets a good painting by R. R. Epperly who, I think, never did another cover for them ever. The weird thing is that in the story the monster is very much a blobby pile of gunk (an “ooze” if you will) but the painting shows what is clearly an tentacular octopus of some sort. Still, I like its haunted eyes. Also, what’s that dude going to do with a shotgun in one hand and a cutlass in the other? Pick one, man!

As an aside, “Ooze” is a fairly middling story – got a fair bit of the ugly racism (and classism!) of the time in it, so be aware if you decide to chase it down. What is interesting is that it’s much more of a sci-fi story than what you’d think of as a “weird tale.” Of course, science fiction didn’t exist yet either (no matter what anyone will tell you!) since Hugo Gernsback’s magazine AMAZING STORIES wasn’t published until 1926. In these early days, and especially before there were dedicated sci-fi magazines, there’s a fair amount of it in Weird Tales, so much so that there’d be huge running gun battles in The Eerie about whether “planet stories” were weird enough for Weird Tales. It’s an interesting point in the evolution of both genres, and it’s right there from the get-go in Weird Tales #1.

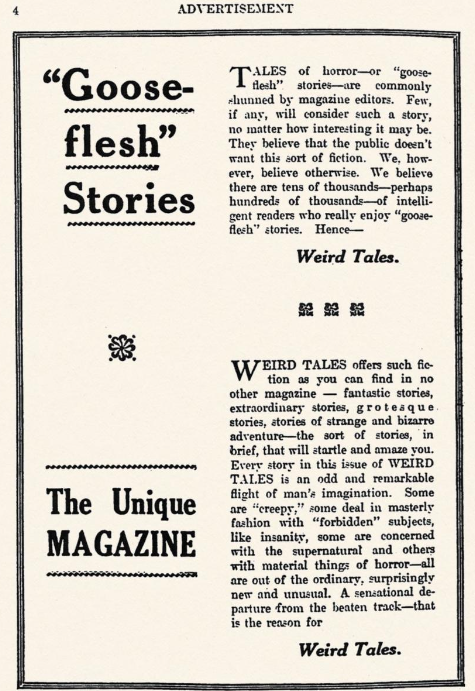

But, anyway, Baird has a hard job – Weird Tales was really the first NEW genre in the pulps, and there wasn’t a depth of writing or writers to draw from, and it shows! Check out this ad, right there on the 4th page of the magazine, just after the ToC:

It’s an advertisement for ITSELF, right there in the magazine, trying to give the reader a way to approach this collection of stories. It’s super interesting to see the creation of a genre in real time in the magazine itself!

Interestingly, the story we’re going to look at today is written by Farnsworth Wright. Wright would step into the editorship of Weird Tales after Baird leaves in 1924, and is probably one of the most important figures in the early history of horror (something for another time, too). At this point, Wright is just a writer; he’ll get another story in the next issue of Weird Tales, at which point he’ll be hired by Baird as an editorial assistant. But, on to his story:

“The Closing Hand” is super short; a scant two-page haunted house story. The writing is overwrought to the point of parody, which I think was Wright’s intention. This isn’t juvenilia; Wright had written and been published in college and afterwards too, and his literary sophistication is evident from those pieces. I think Wright is using this short story to distill the haunted house tale down to it’s barest, most elemental parts, and to do that he’s got to speed-run the language used. Here’s the beginning; note the ripe-to-the-point-of-fermenting purple prose used to set the scene:

Rich, sloppy, bubbling language; it’d be self-indulgent if it was meant to be taken seriously. To be clear, it’s not tongue-in-cheek either; it’s Wright going overboard, reveling in the cliched conventions of the haunted house. There’s decay and abandonment and the aura of wrongness about this place, all very standardized to the point of banality.

We’re then introduced to the victims of the story: two sisters, an elder sceptic and a younger ‘fraidy cat convinced that the terrible old house is haunted. Of course they’ve been left alone, sleeping up in an attic while their mother is out at, I dunno, one of Gatsby’s parties or something. The younger sister wishes they’d gone with her, but the older sister scolds her, pointing out that SOMEONE had to stay in the house because of all the silverware. Get a dog guys, damn!

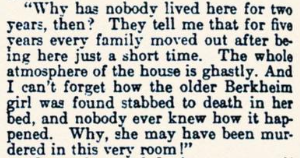

The younger sister than helpfully provides some exposition:

Not gonna find that in the zillow listing, lemme tell you what!

Anyway, the inevitable happens: there are furtive sounds in the night from downstairs, and the older sister heads off to investigate, leaving the scared younger sister alone in the upstairs room. And then she doesn’t come back.

Wind rattles the house, and then there’re strange creeping sounds, as if someone (or…someTHING!!!!) is ascending the stairs towards the attic bedroom. The younger sister begins to imagine what it could be, what horror is climbing towards her, and this is where the story gets the most fun; the sister rattles through a list of the basic horror tropes, scared in turn by the idea it might be a ghost, an undead body fresh from the grave (and “gibbering in terror it could not tear the cerements from its face” which is a great image…the horror itself is frightened by its condition!), a wild animal, or a murderer who, having killed her sister, has come up to finish the job. Then, something enters the dark room, crawling towards the bed…the younger sister reaches out, searching for the thing that comes ever closer, closer, closer, until her hand is suddenly gripped in an iron, cold claw and…she faints!

Here’s the end:

Not necessarily the most surprising of endings, sure, but I think it’s interesting for two reasons: 1) it’s pretty gruesome! That’s something Weird Tales, as the magazine where the genre was being created, would have to constantly deal with (maybe we’ll end up talking about C.M. Eddy’s story “The Loved Dead” one of these days…) but also 2) it’s interesting to me that Wright, the future editor of Weird Tales, was writing a barebones genre study in the very first issue of the magazine. I mean, there’s not really any other way to look at this story: it’s like the most economical haunted house tale you could write: 1) Here’s the spooky old house; 2) some victims discussing its spooky old history; 3) something spooky happens to separate them; 4) one of them produces a list of the various spooky things that could happen to the one left behind on their own; 5) oh shit something spooky is happening to the one left behind!!!!

Here’s the thing: Weird Tales is a new magazine. There’s literally been nothing like it on the market before. There’ve been ghost stories and such published in things like Argosy, sure, but here’s a magazine DEVOTED to this inchoate thing they’ve decided to call “the weird tale.” A big part of the magazine is everybody figuring out what that means…what the hell is a “weird tale?” So you end up with a cover story that’s science fiction, and a story by the future editor of the magazine that is dissecting one of the classic expressions of outré literature, the haunted house story. And that’s important, given the way Baird, as the editor, really goes out of his way on many different occasions to tell people not to submit derivative crap.

I think that makes “The Closed Hand” an interesting story – it’ll never be anthologized, because AS A STORY it’s not particularly interesting. But as an exercise, as a genre study, I think it’s really a worthwhile document that shows how, in 1923 at the birth of the formalized “weird tale,” you have people wrasslin’ with these ideas and conventions and clichés, trying to determine what works and what doesn’t, what needs to be discarded and what needs to be explored. That’s fascinating, and it’s fun to get the chance to see how both writers and readers at the time were navigating the dark waters of weird fiction.

Your view of the ugly racism in ‘Ooze’ seems to have coloured your view on the story. As a “person of colour”, I looked for the racism and couldn’t find it! All I found was a well-done delineation of Cajun life on the edges done in the correct dialect. And what on earth is “classism” – the latest university filter?

“Of course, science fiction didn’t exist yet either (no matter what anyone will tell you!)”

So have H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, Robert Louise Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling disappeared into a wormhole? What about E. M. Forster’s classic ‘The Machine Stops’ from 1912. Perhaps you’d like to inform the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction of your discovery. Oh, wait – didn’t ‘Amazing Stories’ do loads of reprints of classics from previous decades.

“It’s super interesting to see the creation of a genre in real time in the magazine itself!” – It isn’t the creation of a genre, that already existed, otherwise ‘Weird Tales’ also would also not have run reprints; ever heard of LeFanu, M.R. James, Henry James, Blackwood, Benson, Bierce, Hoffman, Poe, Irving, Scott, Hawthorne, etc, etc…

It’s the evolution of a the magazine’s internal character and the one aspect it can take claim of was the creation of “sword and sorcery”.

LikeLike

The classism and racism in Rud’s work is pretty self evident in a story where upright and wealthy WASPs are contrasted with the “queer, half-wild” cajuns, or where the use of racial epithets are tossed around casually. Identifying the deeply ingrained and pervasive bigotry and class-prejudice inherent in 1920s America is neither difficult nor groundbreaking, but refusing to see the way it’s baked into both the narrative and the broader genre is either disingenuous or ignorant. Also, pretending “classism” is some sort of modern, liberal invention is both ahistorical and simply incorrect; it’s both a long-lived and powerful tool of historical analysis as well as an important lens through which we can evaluate social conditions and relations in the arts, particularly literature.

Secondly, if you are actually interested in the idea of genre construction and the history of the pulps, I’d suggest you read Samuel R. Delany’s essays on the subject, particularly in his collections “The Jewel-Hinged Jaw” and “Starboard Wine” as well as in his numerous interviews. Briefly, and for your benefit, his argument, from which I draw most of my own views, is that the attempt to extend backwards genres into deeper history misses the point of those genres; Verne, Wells, etc were not writing sci-fi, because that genre as a category did not exist as a framing. They would not have said they were writing science fiction. Similarly, no reader would have said that they were reading science fiction – it was not until the pulps that the critical and conceptual lens of those specific genres were created. In particular, you can see the contentious wrangling that went on regarding what was or was not science fiction, or a weird tale, or whatever, right there in the pulps, where an active and participatory fandom was able to exercise considerable agency over the editorial practices of particular magazines. This is why, for instance, both Farnsworth Wright and Hugo Gernsback put forms in Weird Tales and Amazing Stories where readers were encouraged to write down their favorite and least favorite stories, with explanations, and send them in, and also why both editors took the time to both print and respond to writer’s letters in the magazines themselves – these were the ways in which genre conventions were delineated and argued about. The fact that both editors also took the time to produce numerous reprints actually supports my point – it was BECAUSE there were no agreed upon or concrete definitions for these nascent genres that people had to look to the past and construct a corpus of work that was science fiction or weird or whatever from works that were important or informative. Nothing springs into existence de novo, certainly not literature, but the mistake of CLAIMING that, for instance, Forster was writing science fiction is a category error and a profound misunderstanding of how genres are actually created.

LikeLike